The father of modern black gospel music was Chicago’s Thomas A. Dorsey, who in 1932, in grief over losing his wife in childbirth and his infant son two days later, wrote the classic “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.” You likely know it as Mahalia Jackson’s signature song, sung on many historic occasions, including at Martin Luther King’s funeral in 1968 (by Dr. King’s own request).

But there was another side to Thomas Dorsey: For years he performed barrelhouse and blues as Georgia Tom, accompanying blues queen Ma Rainey and forming the “Hokum Boys” with bottleneck guitarist Tampa Red, and scoring raunchy hits like 1928’s “It’s Tight Like That,” with verses like:

Mama had a little dog, his name was Ball

You give him a little taste, he’d want it all …

I wear my britches up above my knees

Strut my jelly with who I please …

Uncle Bill came home about a half past 10

Put the key in the hole but he couldn’t get in …

In gospel circles, this is often related as the tale of a fall and a redemption, but Dorsey actually crossed several times over between the church and the secular marketplace. American popular music, particularly (but not only) in the black American tradition, is tight, and loose, and twisty like that. The torque that revs its motor is the tension between profane and sacred, sin and salvation, filthy lucre and heavenly credit, Saturday night and Sunday morning. It’s Thomas A. Dorsey, and it’s John Coltrane and Marvin Gaye and Al Green, and it’s Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis, too, making sensual music that sounds like hellfire (to audiences’ pleasure and horror and horrified pleasure) and then rearing back, turning round, and rising up to reach for the ethereal beyond.

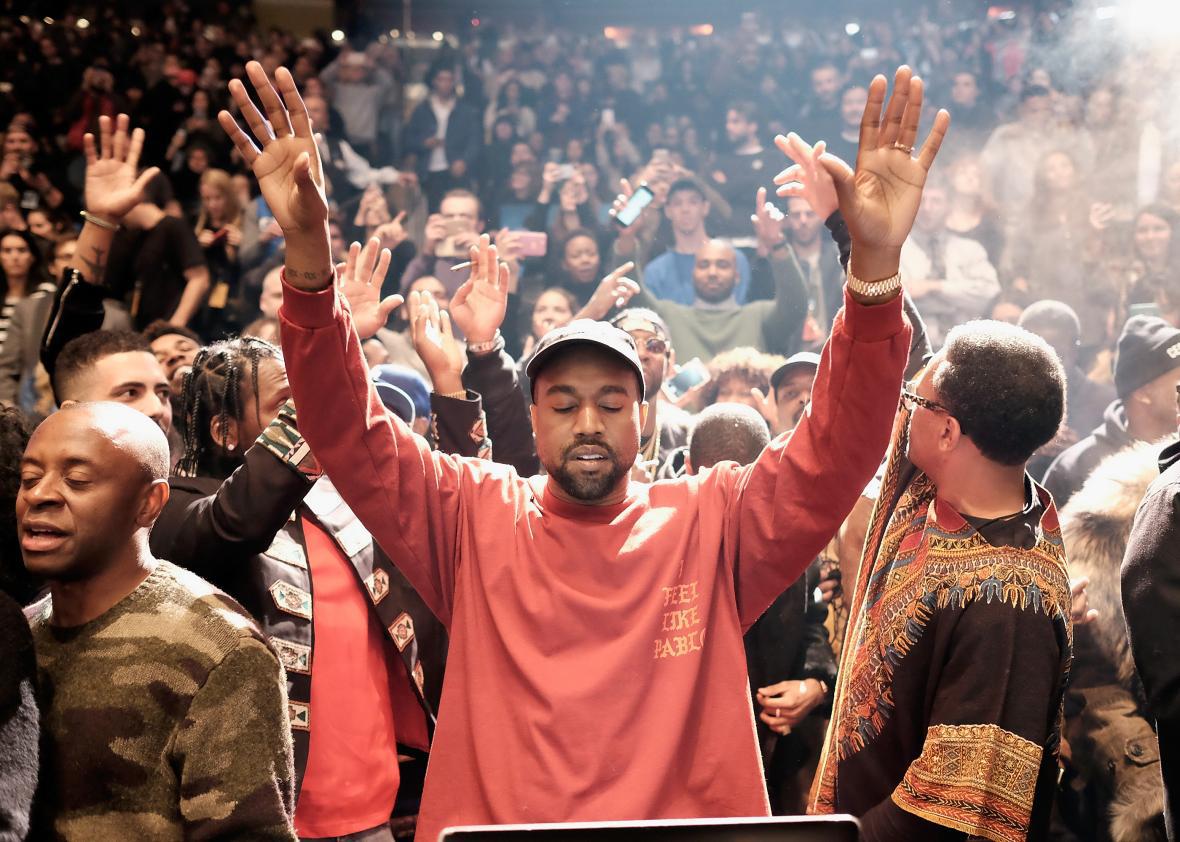

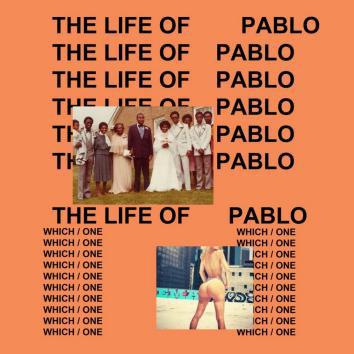

And, embrace him or despise him, it’s also Chicago’s Kanye West, as he’s gone out of his way to note about his new album The Life of Pablo. Last week at his record-release/fashion-show/sanctified-aux-cord-revival-meeting at Madison Square Garden, West announced that it was a gospel record. Later he also tweeted to clarify that the Pablo of the title wasn’t Picasso or Escobar as the “memes” (and some of his own lyrics) were indicating, but instead that famous sinner and outsider struck down and transfigured to bring the good (or, as West might put it, G.O.O.D.) news: the apostle Paul.

G.O.O.D. Music

Certainly its multiple renamings are reminiscent of the former Saul, though the sequence of delays and seemingly impulsive revisions has made it seem less like a revelation or even a set of music than like an extension of West’s Twitter account. The main news it’s made initially is for its myriad offensive and obscene passages about fellow celebrities such as Taylor Swift, multiple West exes, and his own extended family of Kardashianites.

Yet the sounds of voices harmonizing and testifying are all over Pablo, including—on the opening track “Ultralight Beam”—those of the soul and gospel singer Kelly Price and the preacher and contemporary Christian-music superstar Kirk Franklin. Franklin has defied pious critics in declaring his friendship with the hip-hop star—essentially saying “ye of little faith” to anyone who would condemn West or any other human as irredeemable.

Then again, you know, maybe Franklin is just working his own holy hustle. On Saturday Night Live this weekend, he joined a white-clad choir of West’s famous collaborators to do the song, preaching mercy. Meanwhile West prostrated himself on the stage floor—and then hopped up with a smirk to announce that The Life of Pablo was now available for download.

By that point, I must confess, I was damn close to dismissing Brother West’s latest sermon myself. Having listened several times to the stream of the album (partial album, as it turned out) as it sounded being blared from his laptop over the speakers at the Garden, I was beginning to believe it was a last-minute patchwork made by a guy whose mind was much more on his sneaker line. The positive standout moments seemed to come from others, as on Chance the Rapper’s “Ultralight” verse or Frank Ocean’s new coda to “Wolves,” while Kanye’s notable moments were his flights of obnoxiousness about “bitches” and models’ bleached assholes, few of them as funny or entertaining as he’d been before.

Three years ago, with Yeezus, I’d been unable to resist the audaciousness of both the production and the personality, which despite their nasty bits ended up feeling somehow “majestic and inspiring,” as the late Lou Reed (who knew from nasty majesty) put it in his piece on the Talkhouse. Now Pablo was reading to me like a reaction to that album’s relative unpopularity. He was falling back to the prettiness of flipped soul and gospel samples that seduce the people who “like the old Kanye,” as West teases in the album’s wittiest 44 seconds, “I Love Kanye.” Yes, he can produce those sounds like nobody else can, but mixing them with the worst of his ravings into the reality-show–mirrored fame bubble didn’t feel worth the bother. Go manage Hermes, Kanye, if that’s what you’d really rather do. Run for president. I’d have much preferred a whole album of family odes and lullabies like “Only One” (not included here), an 808s and Heartbreak for the Versace-padded nursery. That would have been something new under hip-hop’s synthetic sun.

But then, sistren and brethren, I downloaded and played the final(ish) tracked-out and sequenced and mastered version of The Life of Pablo. And I was struck down. And I was bathed in aural light. It didn’t quite rank as a Damascene moment but, pardon my blaspheming tongue, goddamn. It suddenly mattered more that the song with the reprehensible Taylor Swift line, “Famous,” is also musically woman-powered, through a Nina Simone melody first recreated by Rihanna and then sampled in the original, plus an extensive lift from Sister Nancy’s much-remixed dancehall classic “Bam Bam.” The outro of the Weeknd-featuring “FML” recalls Yeezus, but in an introverted mode, with its warped and spindled use of Factory Records punk-industrial band Section 25’s mostly forgotten single “Hit”—it’s like passing through one of those gravity waves scientists have just discovered between black holes singing each to each out there in the universe, making it seem that West’s frame of reference really might be infinite. The closer “Fade,” which at first seemed mostly like an overdone vehicle for a cool Rare Earth sample, turns out at its full sonic capacity to be like a Chicago House procession out of the Kanye-worship temple and back into the street, or back into your own life.

I could go on, but the point is that in the context of all this sonic landscaping, in West’s kamikaze, mood-swinging way, Pablo now seems undeniably (not half-assedly, as I’d been about to conclude) like an album of struggle. It’s the testimony of a man whose character and circumstances offer not only constant temptation but almost nothing but temptation, in search of what he’s got to offer to his wife and his family other than his potentially eternal bullshit. And while he finds some of it in cracked references to the “God dream,” and to his mom and dad, and to his children as Christ figures wrapped in furs against the wolves in the club, he finds it mostly in sound. He finds it in the rushing “Waves” of Auto-tuned angels bearing him up, in the chilly seraphic glow of Pulitzer-winning composer Caroline Shaw’s a capella voices, in bass and percussion lines (as on “Real Friends”) that are only the tail-end decay of some lost starting place, some vanished rhythmic Eden.

I could hear all that on the bastard album-stream rips, but I couldn’t really hear it. Couldn’t quite make out how, through it all, in this cathedral of sound, even in his crassest moments, West seems like he’s approaching the altar with his story, about to spurn his former ways, then turning tail and stomping back toward the door, spitting, “I’ll strut my jelly with who I please.” If all this were more coherent and obvious, however—and it is almost that obvious—it would not be Kanye West, pop culture’s most antic and irritating shoulder devil, our 21st-century trickster. It would stop being so interesting.

His cellphone has to ring to spoil the soothing groove of the Arthur Russell–sample–based, André 3000–assisted “30 Hours.” He has to put on a whole uninteresting voicemail message as “Silver Surfer Intermission.” He has to change the name of the album multiple times, not release it, release it then unrelease it. He has to pretend he’s not going to include “No More Parties in L.A.,” the track where he dares match verses with rap’s reigning virtuoso Kendrick Lamar, and loses, but still wins because it’s his track. All this hyperdemonstrative Kanye-ing that has little to do with music only makes the music itself appear more effortlessly miraculous.

Maybe you’ll say, with his allusions to mental health and medications prescribed and otherwise, that this is all merely a matter of denial. But it seems to me more the stuff of that torque—that is, of that unhealthy, unredeemed religion I care about, which is art. (As he and Jay Z put it on “No Church in the Wild” a few years past, “What’s God to a nonbeliever?”) None of which means it’s all holy water and no toxic misogynistic effluents, because there are toxins and some people will not want to choke them down, no matter how many spoons of musical sweetening accompany them. But past Pablo’s gates it’s all rock ’n’ roll, it’s all slapstick and vaudeville and dirty limericks and back-door men and snake-oil medicine shows and California cult gurus and the Fruit of Islam, too. West is far from sorting them out for himself, much less for the rest of us.

But when he says throughout the two-part suite “Father Stretch My Hands”—named after another famous old gospel song, sampled here via Chicago South Side pastor, singer, and convicted fraud T.L. Barrett—“I just wanna feel liberated,” I think this libertine really is fantasizing about being saved, rather than the political liberation he’d probably have meant on Yeezus. (Though in truth those two strands never can be pulled apart.) I feel for his suffering as well as the suffering he compulsively seems to inflict, and even sympathize with Kirk Franklin’s wish to lead him out of the wilderness. But for the sake of our wider pop congregation, The Life of Pablo makes me think of another famous conversion story, St. Augustine’s, and lay down this prayer: “Yes, Lord, make Kanye West pure. But not yet.”

Read more in Slate about Kanye West.