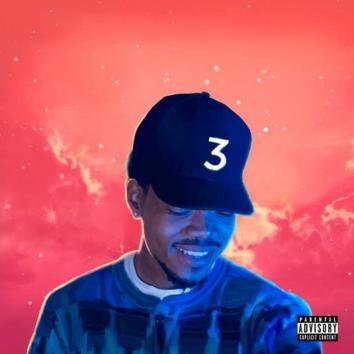

I’m not sure exactly when 23-year-old Chicago emcee Chance the Rapper transitioned from quirky alt-rap charmer to full-blown pop visionary, but I’m pretty sure it’s happened. Chance’s third full-length solo effort, Coloring Book, released for free this past Friday, has the sound and feel of a masterpiece, a watershed in the career of a suddenly major artist. It is irrepressibly joyous and entirely beautiful, and it proves that in 2016 it’s possible to make hip-hop that’s smart without being self-satisfied, positive without being cloying, personal without being navel-gazey. It’s technically been classified as a mixtape but make no mistake, this is an album—and a great one. It feels like music we’ve been waiting for, maybe without even knowing it.

The first thing to know about Chance the Rapper is that his handle is a bit of a misnomer: He’s really an all-purpose vocalist, a killer emcee who also skates in and out of singing, scatting, all manners of vocal play. It can take some getting used to—in a rave review of Chance’s 2013 mixtape Acid Rap, Stereogum’s Tom Breihan opened by declaring that “Chance the Rapper is going to irritate the shit out of a lot of people,” and I’ll admit that for a little while I was one of them. Needless to say, his style has grown on me, but he’s also gotten much, much better at it. Unlike crooner-dabblers like Kanye and Drake, Chance can really sing, his sweet but commanding voice wielding sneakily precise intonation and a great rapper’s sense of time and phrasing.

Coloring Book is absolutely bursting with melodies, courtesy of horns, pianos, guitars, and above all voices. The album’s opener, “All We Got,” features the Chicago Children’s Choir, and throughout the album hooks are provided by the likes of Jamila Woods, T-Pain, Justin Bieber, and of course Chance himself. The album’s third track, “Summer Friends,” featuring Chicago R&B luminary Jeremih, comes on like a futuristic version of Stevie Wonder’s “Love’s in Need of Love Today,” which is saying something since even at 40 years old, “Love’s in Need of Love Today” still sounds pretty damn futuristic. One of the more extraordinary aspects of Chance’s album—and a quality that places it squarely in the tradition of late-period Kanye West, Chance’s Chi-town forefather and primary musical inspiration—is how stuffed it is with guest appearances while still sounding totally organic. This album is not simply Chance the Rapper and his Famous Friends; rather, every track feels perfectly crafted for the people who appear on it, and they for it.

Chance rose to prominence with his 2012 mixtape 10 Day, and Acid Rap solidified his reputation as rap’s amiable, tuneful weirdo, the kind of emcee whose music shy college kids put on and hope their crushes overhear. Since then his profile has only risen, with a flood of show-stealing guest spots and 2015’s Surf, a full-band project released with Donnie Trumpet and the Social Experiment. In December, he touted himself as the first independent artist in history to play Saturday Night Live (Chance, a devout believer in Industry Rule No. 4,080, has yet to sign a recording contract). He brought the house down and returned a few months later alongside Kanye West to debut “Ultralight Beam,” the stunning opening track on West’s The Life of Pablo, an album that’s 3 months old and feels like it’s been out for five years.

West has claimed that Pablo is a gospel record, insomuch that a gospel record can contain fantasies about having sex with Taylor Swift and promises to “fuck the church up by drinking at the Communion.” It’s a work that lunges at the salvation and fails to grasp it, thrillingly. (As Slate’s Carl Wilson wrote back in February, channeling St. Augustine: “Yes, Lord, make Kanye West pure. But not yet.”) Coloring Book, on the other hand, feels like the first great hip-hop album to successfully channel the centuries-old musical traditions of the black church without anything like pretension or irony. This in itself feels like something of a miracle. I say this with the utmost love but hip-hop is a profane music and always has been; its energies aren’t celestial, but fully flesh-and-blood. We don’t generally expect rappers to take us to church unless it’s to rob the preacher for the offering.

Coloring Book feels sanctified without being sanctimonious, spiritual without being preachy. It’s doesn’t tell you it’s out to save you, it just does. The best American sacred music exists beyond the realm of mere words, overjoyed in its conviction that language is insufficient; Coloring Book manages to capture this joy and power even when its concerns stay secular. The spirit runs through everything here, from the choir on “All We Got” to the pulsing house thump of “Highlights” sound-alike “All Night” to the dreamy, druggy “Smoke Break.” And for all the joy and celebration, Chance isn’t hesitant to bare his teeth: “Jesus’ black life ain’t matter/ I know—I talked to his daddy,” he remarks on “Blessings,” the album’s most overtly gospel-infused track. It’s a crushing line, made even more so by the beauty of its musical surroundings.

If there’s one song on Coloring Book that seems destined for the cultural stratosphere, it’s “Same Drugs,” a gorgeous ballad that conjures images of Donny Hathaway and Elliott Smith hanging out together in heaven, bumping Late Registration. It’s a song about losing someone that’s steeped in references to the movie Hook, which sounds annoying but totally works. “Don’t you miss the days, stranger?” asks Chance. “Don’t you miss the days?/ Don’t you miss the danger?” “The days” of what goes unspecified, and there’s an interesting if elusive through-line of nostalgia that runs through much of Coloring Book, a yearning for purity from someone trying to get back to innocence. In future years, we might hear it as nostalgia for the days before this album changed the course of Chance the Rapper’s career.

Back in March, when Phife Dawg of a Tribe Called Quest died, I had an exchange with a friend (and fellow Slate contributor) about how it felt like there was a gap in contemporary hip-hop that Tribe (and, equally, De La Soul) had once occupied, artists making music that was smart and sophisticated and righteous while still being vibrant and sexy and fun. Chance was born the year Midnight Marauders came out—the only thing about him that’ll make you feel old—but Coloring Book has made me feel like that niche is once again filled. Praise be.

But as formidable legacies go, Native Tongues aren’t the story here. “Kanye’s best prodigy/ He ain’t signed me but he proud of me,” Chance declares on the album’s last track. Kanye West is all over this record and not just in the sense that he makes a guest appearance on its opener, which he does. Coloring Book is a love letter to God but also to Chicago and the city’s musical culture that Kanye has repped so ferociously these past 12 years. West might be contemporary popular culture’s most polarizing figure, but listening to Coloring Book these past three days—an album so irresistible, so impossible not to like—took me back to the days of The College Dropout, when the old Kanye, chop-up-the-soul-Kanye was the one thing we all agreed on. Coloring Book feels like a loving devotional to West, a gift to him and to us. It takes a monumental talent to make music like this, and more than one sort of deity to inspire it.