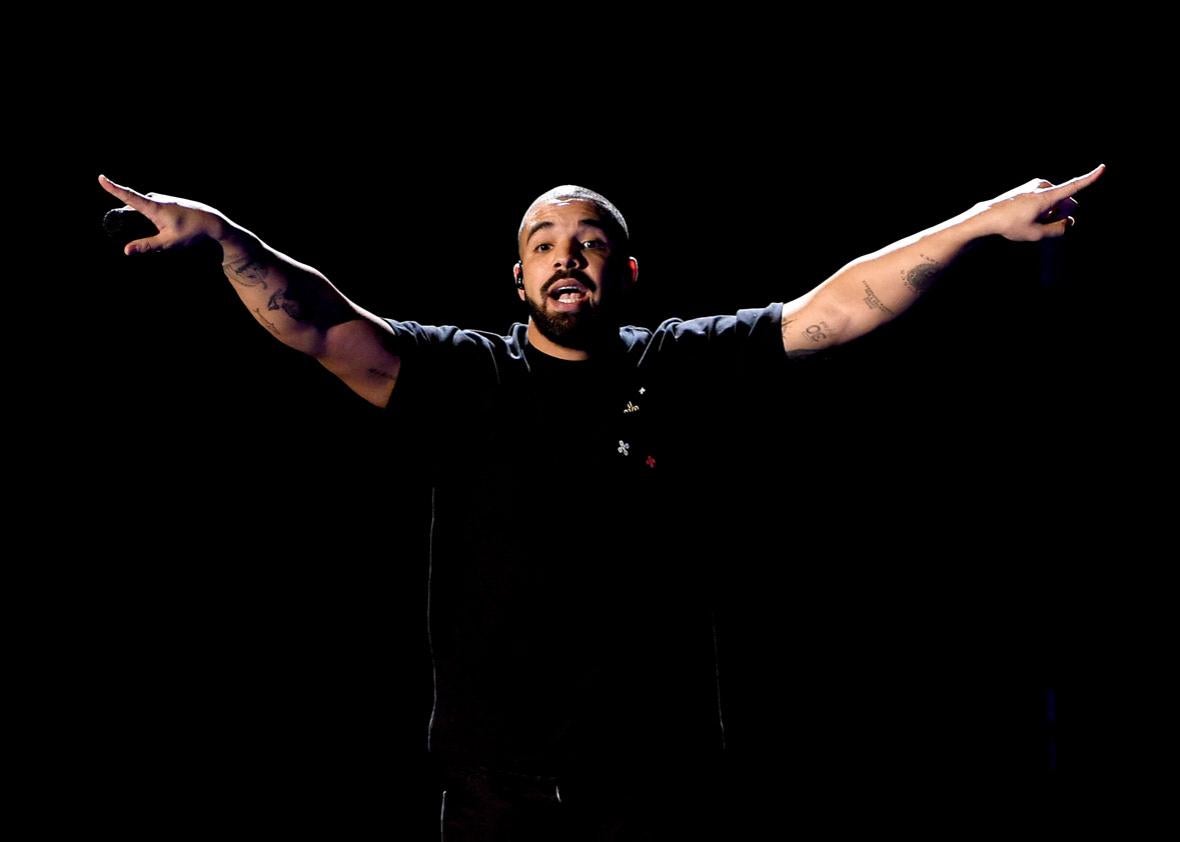

I didn’t know what to expect from Drake’s More Life, a 22-track “playlist” that arrived on Saturday night with relatively little advance hype and only the vaguest sense of what the thing actually was. A few days later I’m still not sure what it is, other than a startlingly excellent piece of work that leaves last year’s commercially overwhelming, musically underwhelming Views feeling like a feint. More Life is long and meandering but never exhausting, its sprawl conjuring the infinite and living quality that a playlist often takes. Front to back, I think it’s the best album of Drake’s career, even if it doesn’t have a front or a back and isn’t even an album—paradoxes that feel like the most singularly Drake thing about it.

More Life is compulsively cosmopolitan and collaborative, a pan-Commonwealth rap album that folds Toronto into East London into Kingston into Johannesburg into who knows where else, stops over in Atlanta, and then drops the whole thing onto the internet. It follows in the footsteps of Beyoncé, Rihanna, Kanye, and Chance in its conceptual challenge to the album-as-form, but it also feels like a conceptual challenge to something like Drake-as-form. One of the reasons More Life succeeds so well is that it’s the first full-length work Drake’s made that seems to recognize that Drake, himself, isn’t all that interesting. Drake is an extraordinarily talented musician with an Achilles’ heel for navel-gazing, a tiresome but lucrative tendency that’s allowed him to become the voice of a generation that enjoys living in public almost as much as complaining about living in public. All this can obscure the fact that, as Stereogum’s Tom Breihan has argued, Drake has the best ear for talent in music, and his greatest asset as an artist is his flair for putting equally (or sometimes even more) talented people in dialogue with each other.

More Life feels like Drake taking a well-deserved and perhaps overdue vacation from Drake, or at least from “Drake.” Its cover boasts a photo of Drake’s father and is credited to “October Firm,” and there are several tracks on which the 6 God’s presence barely registers. “4422” is given over to R&B crooner Sampha while “Skepta Interlude” is a showcase for the British grime rapper Skepta. Many of the project’s best moments come via other people, such as Quavo’s turn on “Portland,” Jorja Smith’s surreal digitized hook on “Jorja Interlude,” and the sampled specter of Jennifer Lopez’s “If You Had My Love” on “Teenage Fever,” a sly and blessedly fleeting allusion to Drake’s personal life. Two of More Life’s highest points arrive courtesy of Young Thug, who contributes a showstopping verse on “Sacrifices,” (“You come with beef, I eat the beat”), then takes another feature on the glorious “Ice Melts,” the album’s penultimate track and a song that feels destined to rule the spring, and perhaps the summer as well.

The production on More Life is customarily exquisite, handled by a raft of up-and-coming OVO producers and occasionally by Drake’s longtime right-hand man, Noah “40” Shebib. It’s cutting-edge music warmed and softened by pop accessibility: Unlike some of the fussier avant-gardism of recent-period Kanye West (who takes a guest appearance on the airy, dreamy “Glow”), More Life feels like music that exists to be enjoyed first and foremost. From trap to dancehall to house to grime to so much else, there’s a treasure chest of influences and inspirations at play here, with “play” being the operative word.

Views was Drake’s safest and most unadventurous album to-date, a work that sometimes felt like a marketing seminar disguised as music. Its staggering commercial success made me fear that the Drake of “0 to 100/The Catch-Up,” If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, “Hotline Bling,” the one-two punch of “Charged Up” and “Back to Back,” and other post–Nothing Was the Same, pre-Views works that found him straying from confession towards a more aloof, half-ironic swagger would prove to be merely a phase. More Life finds him recovering that productive and compelling sense of distance in fun and often funny ways. “Free Smoke,” the album’s opener, is a ragged reminiscence on harder times that also contains pointed jabs at Meek Mill and some self-deprecating gossip-pages humor (“I drunk-text J. Lo/ Old number, so it bounce back”). The last 45 seconds or so of “Can’t Have Everything” is a voicemail from Drake’s mom, a touching and hilarious bit of tough-love encouragement that ends with a presumably pre-election appeal to idealism: “When others go low, we go high.”

Hip-hop has never seen a spongier musician than Drake, just one of the reasons that he’s among music’s most divisive stars. Drake has frequently been accused of cultural appropriation, and if More Life is any indication, he’s not terribly bothered by the charge. The faux Jamaican patois that’s been a staple of his music since If You’re Reading This… has never felt more central to his sound, and More Life finds him strolling remarkably far down the corridors of British grime. “No Long Talk,” which guest stars English rapper Giggs, also features Drake donning a gleefully fake East London accent, and we’ll soon have Drake to blame for the coming wave of American teenagers saying “blem” and the attendant wave of American parents Googling what “blem” means.

These are complex topics, and the line between cultural appropriation and more material forms of exploitation is rarely a bright one. Is Drake’s patois as ethically dubious as Meghan Trainor’s “blaccent,” and if not, is this because white American expropriations of sonic American blackness are so laden with histories of plunder and violence? Or is it because Drake’s music is just light-years better than hers? Or are these even separable questions? I don’t have the answers, but I know they exceed the subject of a single musician, even one as self-evidently significant as Drake.

More Life is great music, and it’s not music that would have been helped by Drake conforming to anyone else’s ideal of sonic Canadian-ness, whatever that might be. Furthermore, its generosity with the spotlight is its strongest aspect both musically and politically: If More Life leads to more U.S. listeners checking out Skepta’s Konnichiwa, one of my favorite albums of 2016, then as far as I’m concerned that’s a great thing. The 22 songs here feel like both the present and future of music, a present and future that have never felt more like Drake’s world.