Frank Ocean and the Wave of Anti-Pop

On his new albums, the category-defying singer gives us what we need, though it may not be what we want.

Screenshot via iTunes.

As the season slowly downshifts into late summer, it seems that we can define 2016 in music not only as a year of loss and mourning (of Prince, David Bowie, Merle Haggard, and many more), but as the year of never quite giving the people what they want.

No consensus “Song of the Summer” has emerged, to the point that the question’s lost the sporting excitement it had for chart-pop fans through most of the past decade. New albums from pop oligarchs such as Kanye West (The Life of Pablo) and Rihanna (Anti) were delivered in messily unpredictable ways that seemed to deliberately undermine (while backhandedly extending) their status as events. Drake’s long-anticipated Views dispensed a fistful of hits, but in its sprawl and bagginess the whole fell flat as the career-topping statement that had been expected.

Even the seeming exception, Beyoncé’s landmark audio and video album Lemonade, was an uncompromising self-assertion that catapulted it far beyond the steady pop pleasures many more casual listeners had assumed she stood for. (As Saturday Night Live put it, for much of America it was “The Day Beyoncé Turned Black.”)

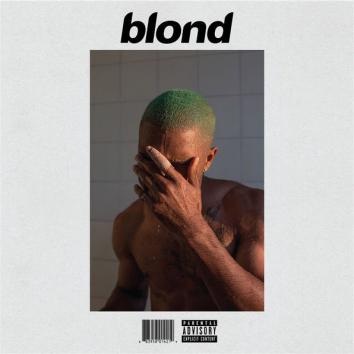

Then, on Saturday, after years’ worth of feints and broken pledges, the rising hybrid-R&B star Frank Ocean finally released, via Apple Music, his thirstily awaited follow-up to his 2012 breakthrough Channel Orange, the legendary-in-advance Boys Don’t Cry. Except that it’s now called Blonde (or Blond, if you go by the cover art). And it was preceded by a whole different record, a 45-minute video album called Endless, with 18 other songs. Plus a 300-plus-page, glossy art-and-fashion magazine that actually is called Boys Don’t Cry and includes moving mini-essays by Ocean (on the model of his Tumblr), a slightly varying CD version of Blond(e), and an all-caps poem from West about McDonald’s fries.

So surely he’s given the people even more than what they wanted? Yes, except that almost none of the music here is likely to serve as a pop self-coronation. And that was the outcome devoutly wished by many fans of more melodic Channel Orange tracks such as “Thinkin Bout You,” “Bad Religion,” and “Super Rich Kids.” Both Endless and Blond(e) are fuzzy meanders, whether barefoot-on-shag-carpet or stoned-on-L.A.-freeway. The music with the video stream forms an extended R&B story suite, one song blurring into the next, and the more official album is an experimental, stop-and-go collage of styles and impulses. They each have many moments of great beauty and emotional vulnerability that make them more than worth a listener’s attention. But in step with the 2016 zeitgeist, they also resist any assimilation as pop blockbusters.

What’s happening here, if what it is ain’t exactly clear, is that some prominent citizens of Pop Land are casting dissenting votes. The most well-crafted, studio-wizarded kind of pop music reached a kind of apotheosis in 2014–15, with records by the likes of Taylor Swift, Ariana Grande, the Weeknd, Pharrell, Justin Bieber, Bruno Mars, and (in another mode) Adele dominating not only charts, but also critical praise. The impish, master Swedish producer Max Martin and his acolytes represented the collective genius of the day. Even nominally alternative music was enjoying a heavy flirtation with pop forms. (Let Grimes stand in for many others here.) Commercial and cultural waves both crested around the truth that there is no inherent contradiction between populism and artistic quality, enhanced by the aggregate effect of online herd movements.

In 2016, though, with the waning of the Obama era and the waxy orange glare of the Trump moment, populism is wearing an uglier face. And it’s not a coincidence that so many high-profile black American artists, in the wake of relentless death-by-police news and the response of Black Lives Matter, are electing to be less conveniently legible. Like the American polity, pop’s mirror image of mass cultural unity has splintered.

Unlike many other artists, Frank Ocean is generally not making explicit black protest songs—though he does cry out on Blond(e)’s lead track “Nikes,” amid nods to musical fallen heroes Pimp C and ASAP Yams, “RIP Trayvon, that nigga look just like me.”

More often, Ocean is plunging his energy into staking out space between the hip-hop hypermasculinity he’s inherited and the queer sensibility he came out into when he published, around the release of Channel Orange, a declaration about falling in love with a man. (The note was widely interpreted as a statement of bisexuality, but Ocean has said he rejects “labels and boxes.”) With rare exceptions, the romantic and sexual experiences he relates on these records use gender-neutral narrative, and when they don’t, they’re fairly evenly split between masculine and feminine references—there are conquests of “pussy” but also a direct reference to “the gay bar you took me to” in the disappointing-date tale “Good Guy.” And by queer-slang convention, some of the “she’s” here might be colloquial gender flips.

He describes his fascination with cars as a “straight boy” tendency that he “consciously” would prefer to be “bent.” And he sings in a couple of places—and mumbles in one recorded conversation fragment—that he doesn’t get with women anymore (though like most straight male rappers he still calls them “bitches”). So his sexual identity may have shifted a few more degrees since his earlier self-revelations, as also hinted by his sweet poem “Boyfriend” in the Boys Don’t Cry zine.

There’s ample nostalgia (one might say ultra nostalgia) on both albums, as is Ocean’s wont, with Endless seeming to center around a past but never-forgotten love affair, and Blonde/Blond (again, gender undetermined) containing a running theme of memories of faded teenage summers and the first stirrings of desire that makes its much-delayed release date feel deeply well-timed after all. Ocean also retraces his own trajectory from his New Orleans youth to his post–Hurricane Katrina migration to Dallas (there are multiple references to Texas, and his desire to escape it, too), then to Los Angeles and now a globalized fame. One of its many class-conscious thrills comes in the final track, when he proudly tells his mother that not only does he no longer work “on a schedule” (an elbow to the haters) for “minimum wage,” but now he works for “$400, $600, $800K.”

In parallel with West’s Life of Pablo and Chance the Rapper’s Coloring Book, there’s a thread of contemporary Christian gospel that runs through the music. Gospel star Kim Burrell makes a cameo on the stirring “Godspeed.” But Ocean’s spirituality is painfully divided, and (as on Orange’s “Bad Religion”) he alternately frets over and revels in his plight as a sinner in the eyes of the traditional church: “In hell, there’s heaven,” he sings on the arresting “Solo.” That’s followed up by a reprise in which ex-Outkast star André 3000 lends a blistering rap with an apparent anti-Drake diss about the current state of hip-hop’s work ethic. As if to suggest that alienation from one’s own culture comes in many forms.

Boys Don't Cry

Ocean’s mom’s other appearance is in a recorded voice message lecturing him to “Be Yourself” and avoid drugs and alcohol, which is immediately followed on “Solo” by a fond reminiscence of doing a lot of acid. Drugs, mostly pot (described on “Nights” as “a cheap vacation”), are omnipresent on Blond(e). Often floating off into cloudy surreal-existentialist rambles (its other prime spiritual mode), it’s a stoner record, better heard in a mood of hazy indulgence than with targeted focus. Surprisingly, near the album’s end, Ocean claims that he’s been abstaining for a year in order to finish the record—and then celebrates by sparking one up.

His mother’s homily doesn’t need to be here, but it’s as if Ocean cannot let a single one of his major themes go untroubled. These are albums about ambivalence and self-interrogation. Hear the tortured shout “I can’t be brave!” on “Seigfried,” a song that borrows a mythic warrior figure from opera, that most queer and least street of genres, as a proxy in Ocean’s struggle over whether to live on the “outside” or to seek a suburban bungalow with two kids and a pool. His voice often reminds me on these albums of another opera fan, Rufus Wainwright, who also gradually shifted away from received song structures to air his inner monologue in more daring diva arias.

Endless, as its initial Isley Brothers–via-Aaliyah cover “At Your Best (You Are Love)” indicates, is in one sense the more conventionally pop and R&B of the two sides of this weekend’s Ocean overflow. Yet the whole album is opened and closed by parts of the song “Device Control” by German artist Wolfgang Tillmans (better known for his photographs of underground dance scenes and polymorphously perverse sociability). In Teutonic techno pokerface, the track makes Kraftwerk-like fun of smartphone marketing, a definite nose-tweak to Ocean’s sponsors at Apple, serving to ironize and queer the very medium that’s delivering the music. Repeatedly, as well, Endless breaks out into skittering fashion-forward club beats in the style of Arca, the shape-shifting U.K. transgender producer who is only briefly hands-on here but serves as a sonic lodestar.

The visual component is a process-art video of multiple close-but-never-touching Frank Oceans painstakingly constructing a spiral staircase to nowhere, over what’s viewed as 45 minutes but obviously took days or weeks. It’s like a compressed version of 1960s Andy Warhol durational films such as Eat, Sleep, Empire, or Blow Job, which tested the limits of viewers’ tolerance for boredom, as a deadpan dimension of camp. Those stairs lead to Blond(e), the video implies, making the stranger work the primary text. Yet both albums, against the background of Ocean’s long withholding tease, prioritize development and change rather than radio-friendly products.

On another level, Blond(e) is the more pop project in its trespassing eclecticism. It poaches from all kinds of sources, with Elliott Smith’s “A Fond Farewell” bumping up against the Wagner reference on “Seigfried” and Stevie Wonder’s cover of the Carpenters’ version of Burt Bacharach’s “Close to You” infusing Ocean’s track of the same name. But most pivotal are the melodic quotations from the Beatles’ “Here, There and Everywhere” in Blond(e)’s catchiest highlight, “White Ferrari.”

Perhaps Paul McCartney should have whiled away his “FourFiveSeconds” with Ocean instead of Kanye and Rihanna. In fact, Blond(e)’s overall hodgepodge of sounds and forms is in the hippie flea-market spirit of the second disc of The White Album. (“Pretty Sweet” even has a Father Yod–style communal cult choir!) Ocean’s opening boast that he’s “got two versions” could also prompt thoughts of Two Virgins, John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s first collaborative album (which carried on in the warped musique-concrète mode of The White Album’s “Revolution 9”). That might seem a stretch, except that Ocean’s “Nikes” video plainly plays on the same pun, showing a pair of young girls and two statues of the Virgin Mary as Ocean crows out the “two versions” line.

Blond(e) and Endless have one more thing in common with a vintage Lennon–Ono joint: They include too many tedious tangents and indulgences, at least if you’re not listening high. Most of their material is not going to be so captivating as background listening or, despite all Ocean’s automotive references, as anthems to blare out from your ride. Settle in with headphones and the lyrics, though, and it’s the confidential closeness—not to mention the teasing withdrawals—that can make them seem like exactly what you need to hear right now. Drake may have just missed conquering the summer by cooing that he needs “One Dance.” But Frank Ocean gets closer by implying that 2016 really needs two, three, a thousand colliding dances, even if they hazard tripping us up and leaving us in a tangle of limbs on the rug, dance floor, or pavement. As we seek out what’s to follow the late great pop monopoly, it just might be the right move for the moment.