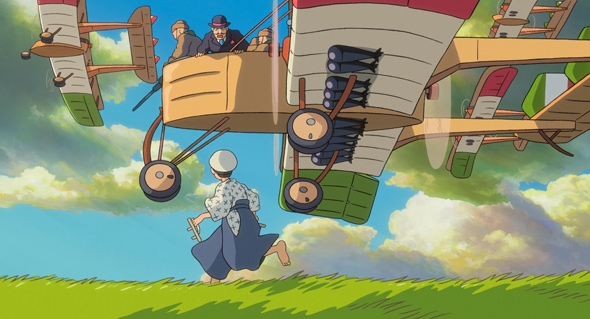

The Wind Rises

Hayao Miyazaki’s final film has the sweep of a David Lean epic and the dreamlike quality of late Kurosawa.

Photo courtesy Studio Ghibli/Nibariki

After you watch The Wind Rises, come back and listen to Slate's Spoiler Special:

Forgive me if I get verklempt about Hayao Miyazaki’s retirement from filmmaking before I even start reviewing his self-declared final film, The Wind Rises. The great Japanese animator, now 73, is one of those artists I feel lucky to have shared an overlapping lifetime with. He’s in the company of Maurice Sendak and Dr. Seuss and Margaret Wise Brown—people able to produce work for children that resonates far beyond childhood, perhaps because they somehow retained access to a part of their earlier selves most of us lose somewhere around the age of reason. Miyazaki’s greatest films have the organic quality of ancient fairy tales: The benevolent forest creatures in My Neighbor Totoro or the bathhouse-frequenting monsters of Spirited Away seem to spring full-blown from both Japanese folk culture and the deepest recesses of preverbal memory.

Miyazaki creates complex fantastical worlds that function according to their own mysterious but incontrovertible logic—and then embeds those worlds within equally specific real-life settings (so that, for example, the magical undersea kingdom in Ponyo believably exists side by side with the bustling small port city where the human hero, Sōsuke, lives with his mother). The interpenetration of reality and fantasy, memory and imagination, and past and present often constitutes an explicit theme in his work—never more so than in The Wind Rises, a biopic of the Japanese aviation engineer Jiro Horikoshi that also seems to function as a kind of vicarious autobiography for the director. Like Jiro, Miyazaki came of age in a ravaged postwar Japan, though in the engineer’s case, the conflict in question was the first world war, not the second. And of course, like the absentminded, idealistic Jiro, Miyazaki would grow up to become a kind of professional dreamer, a single-minded creator of beautiful, intricate things. In Jiro’s case, these beautiful things—most notably his design for the Zero fighter plane, which became one of Japan’s most effective weapons in World War II—were requisitioned as implements of death, an irony that suffuses every frame of this dark and difficult film, which, it should be stressed, is not at all for young children. Between its upsetting wartime imagery, its often-technical dialogue (a major scene involves a group of engineers debating the best rivet), and its long, companionable scenes of “historical smoking,” The Wind Rises is as adult as a clean movie can get.

The Wind Rises opens on a pair of playful dream sequences, as the young Jiro (voiced by Joseph Gordon-Levitt in the English-language dub) envisions himself flying over the countryside in planes of his own design, and later, engaging in some exhilarating wing-walking with the Italian aviation designer Giovanni Caproni (voice of Stanley Tucci). From there, we cut to a slightly older Jiro on a steam train to Tokyo, where he’s studying engineering. After an earthquake derails the train (in an extended, terrifying sequence that seems to personify the 1923 Kantō quake as a malevolent living entity), Jiro helps a young girl and her nanny find their way to safety. Many years later, when that girl grows up (to be voiced in English by Emily Blunt), Jiro will meet her again and fall in love with her, only to see their future threatened by the tuberculosis epidemic that swept Japan between the two world wars. All the while, Jiro and his best friend Honjo (voice of John Krasinski) are struggling both to succeed as engineers and to please their cranky, diminutive boss (voice of Martin Short), one of the few characters in this sometimes dour epic who occasionally serves up some comic relief.

Le vent se lève, il faut tenter de vivre (“The wind is rising, we must try to live”) reads a line of verse by Paul Valéry that serves as both the film’s epigraph and a recurring refrain in its story. (When he meets his future wife on the train, Jiro is reading a book of Valéry’s poems, and she quotes that line to him, the first of several times that a character will consciously cite it). Though it’s just slightly over two hours long, The Wind Rises has the historical sweep of a David Lean picture, complete with panoramic shots of migrating populations against a background of disaster and a romantic orchestral score by Miyazaki’s longtime musical collaborator, Joe Hisaishi. But the film’s oneiric, deeply personal imagery also sometimes recalls Akira Kurosawa’s late masterwork Dreams, in which the director gave vibrant cinematic life to eight of his own real-life nocturnal visions.

Since it premiered at the Toronto Film Festival last year, The Wind Rises has been the object of controversy for everything from its matter-of-fact depiction of the ubiquity of cigarettes in the postwar era (in one of my favorite scenes, Jiro and Honjo sit together in their Tokyo flat, chain-smoking in friendly silence) to its alleged trivialization of Japan’s role in some of the worst atrocities of the 20th century. In South Korea, critics of the film have expressed chagrin at Miyazaki’s elision of the role of forced Korean labor in building the state-of-the-art military aircraft this movie showcases, at times, with something like romantic nostalgia. There are certainly unseized opportunities to delve deeper into the grim historical consequences of Jiro’s passion for innovative aviation design—but there’s also no denying the constant presence, in The Wind Rises, of the twin specters of wartime trauma and survivor’s guilt. Time and again, Jiro’s playful visions of whimsical flying machines are interrupted by images of real-life World War II warplanes exploding in midair or carpet-bombing whole cities, the cruel future reaching back in time to corrupt the innocent present. It’s as though Tombo, the aviation-mad boy who flies his own homemade bike-plane at the end of Miyazaki’s Kiki’s Delivery Service, had been unwittingly swept up in the tide of history and grown up to be a kind of Robert Oppenheimer figure, regarding the fruits of his creation with horror and awe. “Airplanes are beautiful dreams,” Jiro’s imaginary mentor Caproni tells him in an early scene. “Engineers turn dreams into reality.” Then again, as Caproni will remind both his acolyte and the audience soon after, there’s a tricky moral valence to this artist’s privileging of the unreal over the real: “Dreams are convenient. One can go anywhere.”