Man of Steel

Can America stomach a superhero this saintly?

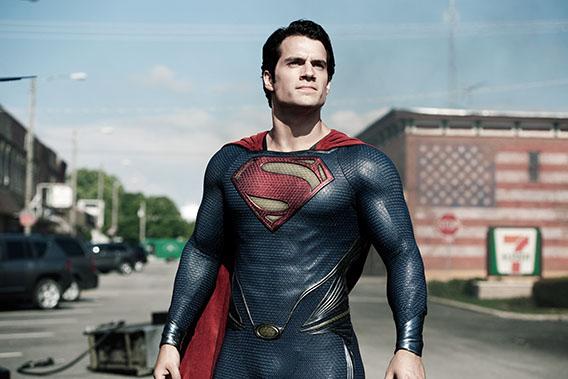

Photo by Clay Enos/Warner Bros.

After you've seen Man of Steel, come back and listen to our Spoiler Special:

A colleague of mine made the astute observation that superhero blockbusters have something in common with medieval religious art. Both rely on rigidly fixed iconographies drawn from a narrow range of canonical subject matter. The individual creator may vary the style, but the terms of the representation are governed by a larger divine or quasi-divine cosmic order: hence the endless variations on the Annunciation, the descent from the cross, the first appearance of the cape and tights, the final fistfight atop a skyscraper. Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel doesn’t aim to turn that cosmic order inside out; this is the work of a man of faith, a director whose whole career has been predicated on his love for the comic and graphic-novel form. But Snyder (300, Watchmen, Sucker Punch) provides an elegantly illuminated retelling of the origin story of that most saintly of superheroes, Superman.

Superman’s saintliness is part of what makes him so hard to pull off in our era of dark, brooding, morally conflicted superheroes. Like Mary Poppins, Kal-El aka Clark Kent is practically perfect in every way: honest, pure, brave, compassionate, filial. He can easily come off as a goody-two-shoes when not played by someone as endearingly modest and self-evidently human as Christopher Reeve, whose hold on the character in the public imagination (or at least mine) has never really let go since Richard Donner’s 1978 Superman.

The young British actor Henry Cavill, who takes over the role here (it was last played by Brandon Routh in the mopey, soon-forgotten Superman Returns), doesn’t have Christopher Reeve’s sparkle—but to be fair, it’s not like he is being directed to generate that kind of radiance. Cavill—a slight, beautiful man whose dimpled chin and introspective eyes suggest John Travolta by way of Montgomery Clift—is only one element in what amounts to a vast project of world- and franchise-building. In fact, we don’t even get a glimpse of the adult Clark (disconcertingly bearded and working under a false name on a fishing ship) until well into the first hour. Until then, we’ve spent most of our time on Krypton, the doomed planet from which baby Kal-El’s parents, Jor-El and Lara (Russell Crowe and Ayelet Zurer) reluctantly agree to launch their newborn in a spaceship.

You would think the imminent explosion of your home planet would be enough reason to send your baby into space, but Kal has a second threat to contend with: the sworn hatred of General Zod (a muted, uncomfortable-seeming Michael Shannon), his scientist father’s former ally who’s determined to find a planet for the remaining Kryptonians to settle on—even if that involves depopulating someone else’s.

The early scenes on Krypton contain some fascinating imaginings of alien technology and design. Superman’s home planet isn’t all dank, dripping tunnels and clanking hardware, but a place of Art Nouveau–style architecture and spacecraft that recall hovering deer ticks (or, in the case of young Kal-El’s space pod, a vaguely phallic unshelled peanut). But as cool as Krypton looks, it’s hard to get invested in Jor-El and Zod’s debate about how best to save their beloved planet when we all know it’s about to be blown to smithereens.

Once Kal arrives on Earth—his phallic pod alighting in the cornfield of Smallville, Kan., farmers Jonathan and Martha Kent (Kevin Costner and Diane Lane)—the story picks up some speed. Snyder cuts nimbly among timelines as we meet Clark at age 9, age 13, and finally a conspicuously Jesus-referencing age 33, struggling to hide his still-nascent but already impressive superpowers from a world he fears will reject him. As the incidents of unintended life-saving begin to pile up—this is a kid who can’t board a school bus that doesn’t plunge off a bridge into a river—Clark’s path eventually intersects with that of Lois Lane (Amy Adams, wonderful as always), a fierce investigative reporter who will stop at nothing to find out the identity of this rumored invincible man. Connoisseurs of the office-romance frisson between Lois and Clark will be disappointed by this movie’s de-emphasis on the Daily Planet as a workplace; we only visit the newsroom briefly, mainly during arguments between Lois and her editor (Laurence Fishburne), who, reasonably enough, is reluctant to run with even a well-sourced “flying man from outer space” scoop.

The last hour is devoted almost entirely to the grand-scale destruction of Metropolis, as the airborne Superman and Zod slug it out spectacularly over a city that’s collapsing on top of its own citizens. Unlike many (too many) similar scenes in recent action films that casually ransack 9/11 for readymade disaster imagery, this sequence is crisply edited and imaginatively staged. Snyder excels at creating big, punchy images that recall a comic-book spread, as when the brawling hero and villain swoosh through the air in convincingly rendered hyperspeed, leaving a long, slowly fading blur over the skyline. But the awareness of the rapidly ascending body count on the ground below them makes the indulgent length of this final battle hard to stomach. Lois and Clark’s first kiss, and the mocking banter that ensues, are also a bit queasy-making given that the supersmooch literally takes place at the foot of a heap of smoking rubble. If this version of Superman is to have a future—as Warner Brothers seems convinced he will, having already green-lit the sequel—I hope Snyder will dial back both the casualty count and the Krypton mythmaking and instead focus on establishing a fictional Earth that’s rich enough to be worth saving.