Everyone Sucks

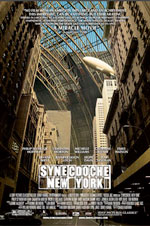

Charlie Kaufman's Synecdoche, New York.

To listen to Slate's Spoiler Special about Synecdoche, New York, click the arrow button on the player: You can also click here to download the MP3 file, or you can subscribe to the Spoiler Special podcast feed in iTunes by clicking here.

Synecdoche, New York (Sony Pictures Classics) is a very sad movie for two reasons. First off, the story, about a theater director who's sucked into the vortex of his own impossible artistic ambitions, is unremittingly bleak, making for one of the most depressing nondocumentary films you're likely to see, well, ever. But secondly—and in the long run, more movingly— Synecdoche is sad because it's a constant reminder, a ghostly double, of the great movie it could have been.

Synecdoche (the title is a pun on the place name Schenectady and the rhetorical device) is the first movie directed by screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, who wrote four films—Human Nature, Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind—that have established him as the Kafka of Hollywood. He's the only major screenwriter with a distinctly literary voice. In fact, he may be the only "major screenwriter," period; how many movies do you go see because of who wrote them? The near-universal plaudits for Eternal Sunshine tended to treat it as a "Charlie Kaufman film," while only mentioning the actual director, Michel Gondry, as an afterthought. And looking back on Kaufman's body of work, it's hard at first to remember which of his two collaborators, Gondry or Spike Jonze, directed which movie. These four films are tied together not by their look, their sound, or their pacing—elements a director controls—but by the writerly virtues they share, their mix of labyrinthine imagination and absurdist wit.

Given all that, the prospect of Kaufman's directorial debut was really exciting—which makes the lugubrious result that much more disappointing. Fittingly, "disappointment" is a key concept in Synecdoche. In an early scene that recurs later as a flashback, Adele Lack (Catherine Keener), the unhappy wife of regional theater director Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman), packs her bags to move to Berlin without him, reassuring him that it's not his fault: "Everyone's disappointing once you get to know them." It's a dispiritingly cynical assessment of human relations, one that we assume the rest of the movie will, at least in part, attempt to refute. But over the next two hours, we'll get to know Caden Cotard very, very well—his desires, his frustrations, his neuroses, and his unpleasant bodily emissions—and, sure enough, as time goes on, he'll interest us less and less.

And time does go on in this movie, with a haphazard, vertiginous motion that splits the difference between Proust and Philip K. Dick. Caden resists the advances of Hazel (Samantha Morton), a sexy employee at his theater's box office, on the grounds that his wife has only been gone for a week. "She's been gone a year," Hazel replies. Later, Caden will fly to Berlin to track down his daughter, Olive (Sadie Goldstein), who's fallen into the clutches of his wife's scary best friend, Maria (Jennifer Jason Leigh, hilariously riffing on the scary-best-friend role she's specialized in ever since Single White Female). "She's 4 fucking years old!" Caden screams, upon learning that Maria has covered the girl's body in tattoos. But Olive, Maria tells him in her newly acquired German accent, is nearly 11.

The movie's sense of temporal dislocation is profound and pervasive and very skillfully done—walking out, you have no idea how long the whole experience lasted (though you're pretty sure it was much too long). Still, Synecdoche contains moments of beauty so aching, you find yourself mentally scrambling to fill in the movie that should have existed around them. Many of these high points involve the main character's relationship with his absent little girl, who pops up in brief, nostalgic tableaux. (If you've seen Eternal Sunshine, you know how brilliantly Kaufman can evoke the sharp pain of childhood remembered.)

But I'm getting ahead of myself, Caden Cotard-style. I haven't even described the theater piece at the movie's center, an untitled Gesamtkunstwerk that Caden undertakes upon receiving a MacArthur "genius" award. After renting out a vast warehouse in Manhattan, he attempts to construct a scale model of his own life, complete with actors playing his wife, his ex-lovers, his neighbors, and eventually himself—a kind of shadow figure (Tom Noonan) is hired to follow Caden everywhere and pretend to be directing his play. The distinction between reality and simulacrum disappears down the rabbit hole: The fake Caden falls in love with the real Hazel, the real Caden has a fling with the fake Hazel (Emily Watson), and an actress hired to play a maid (Dianne Wiest) angles to take over the whole show. Which, by the way, is a "show" only in the most abstract sense; as one disgruntled extra points out during a rehearsal, nearly 17 years have passed without the work ever being performed for an audience.

All this talk of doubling and simulacra sounds terribly cerebral, and at moments, the movie can be—when we hear characters eulogizing Beckett or see Caden cracking the first volume of Proust, even the most bookish viewer may permit herself a roll of the eyes. But Synecdoche's main problem isn't that it overintellectualizes; in fact, one of Kaufman's chief tricks is the punch-to-the-gut emotional scene that comes out of nowhere. The problem is that the movie's worldview, in the end, isn't expansive enough to justify the (quite literal) stage it takes place on. When a takeaway message finally emerges from the film's mad swirl of images, memories, and ideas, it seems to add up to little more than, yeah, people are kind of lame once you get to know them. Or possibly, as an actor playing a priest intones over a fake grave in the play-within-a-movie, "Fuck everybody."

I'm not asking for humanist inspiration here—really, I'm not. I love a glum take on the human condition as much as the next guy. But Beckett was Beckett because he managed to write about what my endearingly depressive brother once called "the slow conveyor belt towards death" in a way that made you glad you were along for the ride. It's wonderful to be allowed once more inside the many mansions of Charlie Kaufman's brain—I hope he never stops writing and never stops grappling with the big questions, the corny embarrassing ones about why we live and love and die. I just never want to have to see this movie again.