In the Belly of the Beast

Woody Allen's alter ego; Steven Spielberg's slave ship.

Deconstructing Harry

Directed by Woody Allen

Fine Line Features

Amistad

Directed by Steven Spielberg

DreamWorks Pictures

Ever since the faux-Swedish era of Interiors (1978), Woody Allen has been squeamishly inching his way back toward the kind of unruly Jewish humor with which he made his name. There were movies that featured increasingly long and wandering takes, then the hand-held camera/inquisitor of the penetrating Husbands and Wives (1992), and then such off-the-wall devices as a Greek chorus (Mighty Aphrodite, 1995) and slap-happy musical production numbers (Everyone Says I Love You, 1996). With Deconstructing Harry, his most determinedly unpolished work since Annie Hall (1977), Allen engages in what a shrink might label "regression therapy": The film is smutty-mouthed and jumpy and free-associative, and Allen does everything but hurl his feces at the audience. The result is more rambunctious--and more fun--than any movie he has made in years. What puzzles me is why it still adds up to something so anemic and coldly distasteful.

Perhaps because Mia Farrow and Claire Bloom published memoirs about their respective monster mates at the same literary moment, Allen seems to have forged a psychic bond with Philip Roth, and has merged himself and Roth into Harry Block (played by Allen), an author whose stories and novels juggle aspects of his own life and the lives of people he knows. Ex-wives, ex-lovers, and would-be ex-siblings are driven to a frenzy by the way he vampirizes their experiences for material and exposes their most embarrassing secrets. And yet, in the face of their rage, Harry affects an oblivious demeanor, looking tender and helpless in a cotton sweatshirt that hangs from his scrawny frame. Meanwhile, he confesses to wanting to "fuck every woman" he sees, and dismisses sundry belligerent exes as "world-class meshuggeneh cunts."

Megastars pop up to help Allen illustrate vignettes from Harry's past and fiction. Robin Williams appears in a surreal identity-crisis short about an actor who finds himself literally out-of-focus, on-camera and off. Judy Davis, Kirstie Alley, Amy Irving, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Demi Moore, and Elisabeth Shue--all acting their little hearts out in a vacuum--are seen either screaming at or nuzzling Harry, or else screaming at, nuzzling, or fellating one of Harry's fictional alter egos (Richard Benjamin, Stanley Tucci, Tobey Maguire). Harry displays little interest in the world-class meshuggeneh cunts he has left behind, but he writhes in anguish when he learns that a gorgeous young blonde (Shue) whom he mentored, and for whom he abandoned his third wife, will soon marry an old friend (Billy Crystal). This jolt--along with the prospect of receiving an honorary degree from the college that once threw him out and having no one to tote along to share the experience--sends him into an orgy of self-pity that masks itself as self-examination.

Deconstructing Harry rattles along, leaping back and forth in time, swerving sideways into Harry's fiction and hellward into his fantasies. An extended sequence features Harry journeying to the lowest floor of Hades (lower even than where book critics reside) to confront the devil (Crystal), who has stolen his fair young thing. In another sequence, Harry, making a pilgrimage to his former college, girds himself with the presence of an agreeable colleague (Bob Balaban); his own son (Eric Lloyd), whom he kidnaps from school; and a tall, sassy black prostitute (Hazelle Goodman) who dispenses bits of street wisdom. The Godardian profusion of jump-cuts feels like a painter hacking at the surface of the canvas with an X-Acto blade to give it sharper edges and texture. The surface of the film is rough-and-ready and frequently hilarious; as a gag-man, Woody lives! It's the thinking underneath that's moldy and embarrassingly adolescent.

Harry's big problem, we're told, is that he "can't function in life, only in art"--which is where he takes refuge when everything collapses, much like the protagonist (Mia Farrow) of The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985). Here, however, the retreat into fantasy is more hopeful, because the fantasy is of Harry's own making--and how about those marvelous stories and characters! Harry, who has learned what a shit he is for an hour and a half, realizes that he's not such a shit as long as he litters the world with literary jewels.

This seems dodgy and off-the-mark. The film is confessional right up to the point where the protagonist has to say something incisive about himself, and then it lapses into what I call the "Amadeus Fallacy," which holds that life and art are poles apart, and that a great and moral artist can also be an amoral baboon. I propose that the separation is not so clear-cut. Philip Roth might well be a lousy human being, but no one could mistake him for an oblivious one: The greatness of his fiction lies in how he holds up every aspect of his lousiness for pitiless dissection. Allen's Harry, meanwhile, is busy leaving one young woman for another even younger, and then failing to attach much meaning to it, or to connect his obsessive fear of death to his tenuous regard for the living. In his heart he still believes that anyone who leaves him is going to the devil. Allen misses the most obvious punch line, the one that might have saved Deconstructing Harry from being so much less than the sum of its parts: that when Harry goes down to meet the devil, he discovers that the devil is himself.

A rtistically, if not commercially, Steven Spielberg has often been the victim of his own virtuosity--an artist whose crackerjack technique is forever running away with itself. I didn't have a clue what he was trying to do in Schindler's List (1993) when he cross-cut between Nazi Ralph Fiennes molesting a Jewess in the wine cellar and Liam Neeson carousing among the Aryans (Was he comparing or contrasting them?), but the sequence was formally brilliant. Wild lapses in taste and judgment have been the rule in Spielberg pictures since his Twilight Zone (1983) episode and The Color Purple (1985). That's why I found the evenness of Amistad a pleasant surprise. After an electrifyingly feral opening, the movie settles down into a cogent courtroom drama, with no real cinematic highs but no jaw-dropping lows, either.

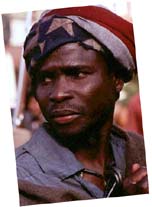

The opening reminds you once more of why Spielberg is where he is. Janusz Kaminski's camera is tight on the blue-black flesh of a slave called Cinque (Djimon Hounsou)--so tight that his rivulets of sweat seem like glittering silver ponds and streams. He's on a slave ship bound for America in 1842, and as he tugs and tears at the spike that holds his chains in place, stroboscopic bursts of lightning make the crimson of his bloodied fingers leap out of the screen. The melee that ensues is death in chiaroscuro--the slitting of throats in the darkness, the gun-muzzle flashes, the waves that sweep over the deck and carry off the gore-drenched crew members. Spielberg must be aware that the shot of Cinque roaring in triumph as he pulls a sword from the belly of the ship's sadistic captain evokes King Kong, that most primal of all white xenophobic movie fantasies. He has set out to make the King Kong that actually happened.

B ut Amistad (the film--and the actual incident--is named for the ship that carried the Africans to America) doesn't stay with the slaves' point-of-view, which is too bad. Spielberg jumps back and forth between showing their perceptions of the New World and viewing them as exotic pictorial objects, at one point evoking Goya's Third of May, 1808 as Cinque holds out his arms, his puffy shirt glowing white, and appeals in primitive English for freedom. Spielberg's work is most vivid when he's in the Africans' heads, as in the flashback sequence that telescopes Cinque's barbaric voyage from Africa, and in the shot of Cinque heading toward the New Haven courtroom where he and his countrymen will be tried for murder. He stares at the masts of a great ship--much like the Amistad--passing over the rooftops of the city. Hounsou is terrific, but so impossibly gorgeous that it seems as if the slave-traders have snatched an African spokesmodel.

Amistad is basically one trial after another, as various parties struggle to take possession of the Africans, from the representatives of the 11-year-old Queen Isabella of Spain (Anna Paquin), to the sea captains who captured the ship, to the abolitionists who hope to use the case to turn public opinion once and for all against the splendid institution of slavery. The film is more or less factual (click for a rundown of the ways it departs from the historical record)--and spends much of its running time on minutiae, both legal and interpersonal. It takes half the movie for the abolitionists (led by Matthew McConaughey and Morgan Freeman) to find someone who speaks both English and Mende.

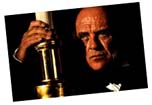

T hat this part of the picture is carried by McConaughey is one of the reasons it sags--not because he's a bad actor, exactly, but because he's a lightweight one, and his features recede under his curly blondish hair, spectacles, and fringe of beard; you might forget at times that you're not watching Woody Harrelson. The film picks up again with the arrival of Anthony Hopkins as John Quincy Adams, the elderly ex-president who is finally prevailed upon (largely due to his loathing of President Martin Van Buren, played to mingy-spirited perfection by Nigel Hawthorne) to mount the Africans' defense before the U.S. Supreme Court. Hopkins might be an overrated actor but he is one inspired ham. It helps when the characters he plays are ham actors themselves--as Hannibal Lecter was, and as Adams is here. The deep voice he developed for Nixon (1995) serves him well: He drops it down and makes it rumble, and like all great orators, relishes the very sound of the words. When he stands before a bust of his father, his forehead sloping back into the frame, you might feel a surge of patriotism, and that the legacy of dead white men isn't always to be shunned.

John Williams' score is a euphonious pastiche of African and Western musical history. Beyond the requisite chants, cries, and tub-thumps comes a bit of bass lowing that resembles the barbed-wire emissions of Buddhist monks. When Hopkins is center-screen, the trumpets and strings recall vintage Aaron Copland. It is a lovely, lovely score, and there isn't a moment when it doesn't tell you how you're supposed to feel about what you're watching. For better and for worse, Spielberg is the best filmmaker alive at giving an audience its bearings.