Drunk on His Own Jazz

Mike Figgis' One Night Stand.

One Night Stand

Directed by Mike Figgis

New Line Cinema

The Jackal

Directed by Michael Caton-Jones

Universal Pictures

One reason I haven't ventured back to a jazz club since I stopped drinking is that I always want to drink when I listen to jazz, the way I always want to drink when I see a Mike Figgis movie. At heart, most Figgis films (they include Stormy Monday, Internal Affairs, and Leaving Las Vegas) are about surrendering to the music of the moment--usually bebop, moody and free-floating, composed by the director himself--and drinking simply comes with the territory. Leaving Las Vegas, ostensibly a tragedy of alcoholism, seems more like an ode to it: The terminal bender of its hero (Nicolas Cage) ends not with the man choking on his vomit in an alley, but in a lyrical death rattle at the end of a physiologically improbable session of intercourse with a miniskirted blond hooker (Elisabeth Shue). The drama in Leaving Las Vegas is the tension between succumbing to the romance of oblivion or soberly clinging to one's horror at a fellow human's self-destruction. In a Figgis movie, though, it isn't much of a contest. Oblivion always has better legs.

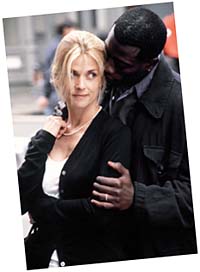

It's even less of a contest in One Night Stand. Like Cage in Leaving Las Vegas, the hero (Max, played by Wesley Snipes) confronts the bs of his life in showbiz and seeks transcendence, only here it's in the form of an affair with a radiant blond, ahem, rocket scientist (Nastassja Kinski). A prosperous director of arty commercials, Max has traveled from Los Angeles to New York City to see his estranged buddy and business partner, Charlie (Robert Downey Jr.), a gay choreographer who is HIV-positive. Facing death in the form of a haggard friend, listening to the Juilliard Quartet perform that most transcendentally death-obsessed of all the final Beethoven quartets (No. 13 in B flat), and fending off a pair of spooky Eurotrash muggers would be enough to drive you into the arms of Klaus Kinski, let alone Nastassja.

P retentious singers sometimes call themselves "song stylists." I think of Figgis as a "film stylist," and he's one of the world's most engaging. Anything goes. One Night Stand begins with Snipes walking along a midtown Manhattan street and explaining his situation to the camera, which goes on to do a lot of illustrative swirling and whip-panning, although Snipes never talks to it again. It stays busy, though: Now it's up in a helicopter with a traffic reporter, now back on the ground fastening on the assorted exotic multinationals who seem to constitute, for Figgis, the population of New York City. At a table in a hotel lounge, Snipes can't keep his eyes from drifting to Kinski, and as they do, the camera makes furtive, zoomy, in-and-out-of-focus moves, the way a real human eye would shift and refocus and look away, the image streaking. When the camera comes to rest, Kinski is breathtaking--not because she's lovely (although she is) but because she has gotten slightly drawn and toothy, and is starting to resemble her late dad. The faint suggestion of a death's-head makes her even more alluring.

Figgis lives for semilit hot kisses with bebop underneath. He fades out on the lovers as they hover over each other in bed, and fades back in on them without any time having elapsed. He must be doing this fade-out, fade-in thing for its rhythm alone, or else he's trying to induce in the viewer his characters' delirium. If it's the latter, it's a mistake. This romance could use less distant flicker and more close-up, uninterrupted interplay. Figgis does induce a subjective state, but less that of his hero and heroine than of a drunk-on-his-own-jazz virtuoso movie maker.

I t turns out that Max's wife, Mimi (Ming-Na Wen, of The Joy Luck Club), is drop-dead beautiful but brittle and shallow. Worse, she chatters in the sack, issuing orders to her studhorse husband in a manner that clearly clashes with his yearning for nirvana. Max's job directing commercials seems like an odd one for such a beacon of integrity, but it is consistent with Figgis' '60s sensibility. In all those comedies about turning on and dropping out, the heroes were ad men who smoked a little dope; had the scales fall from their eyes; and told off their square, racist bosses. This era's variation is having an estranged buddy dying of AIDS: Your life snaps into focus; you realize that existence is fleeting, etc.; and you rail against television as a "frontal lobotomy" and say "fuck you" to your homophobic boss and materialistic friends.

The more abstract Figgis stays, the better: As soon as you see clearly what he's up to, the air of profundity dissipates and you're left with an awfully conventional weeper tricked out with the newest cinematic syntax and self-consciously unself-conscious attitudes toward miscegenation and homosexuality. The picture's only unresolved dimension is its gay one. In a lot of ways, One Night Stand is a coming-out movie manqué. Early on, Max's estranged friend refers to Mimi as "your beard--er, wife," and Figgis seems to be setting us up for Max to get real by falling for a guy. We anticipate an artier In & Out and get Cousin, cousine.

No, that's unfair. We get something rather less canned. The dialogue has an improvised quality--a description that usually means it sounds like a bunch of actors doing improvs, but here means that it sounds like the not-so-lustrous things that people actually say to one another. There are pinpoint glimmers of truth, looks or gestures that you never see when a camera is rolling, when behavior is subtly and not-so-subtly altered by actors' Heisenbergian responses to lights and cameras. These are small, inconsequential things, like the look Wen gives Snipes to re-establish intimacy after a couple they've just had dinner with gets into a taxicab, or when she accidentally whaps him in the face during sex. Figgis brings his full attention to such moments, lingering proudly, and he's right to be proud.

Snipes does the groping-for-words thing as if he studied the Method under Christopher Walken, and it's actually charismatic. This Walken-Snipes Method isn't tentative or thoughtful. It's arrogant, declamatory: Never let them see you mumble. Across a table from Snipes, the wiry Downey begins to do Walken, too, but this grows more difficult as the disease progresses and he runs out of breath. (Note to filmmakers: When a dying man tells a long joke--with great wheezes in an effort to get the words out--it's even more of a drag when the punch line isn't good.) I was glad to see Downey again, even if I wasn't ennobled by watching his character die of AIDS, because he's a whip-smart actor, heroically unsentimental.

I t was Mike Figgis who helped to liberate Richard Gere from the depths of third-rate De Niroisms in Internal Affairs. Playing a sleazebag cop and seducer of other people's wives, Gere introduced some salt and pepper into his hair and the suggestion of dirty secrets into his persona. He continues to ripen well. He's one of the only things to like about The Jackal, Michael Caton-Jones' pompous and coarsely stupid inflation of what remains a superior thriller, Fred Zinnemann's The Day of the Jackal (1973).

I saw Zinnemann's film three or four times at age 14, and loved its low-key, one-step-at-a-time devotion to process--both of the ghostly hired assassin (Edward Fox) out to kill Charles de Gaulle, and of the police on his vaporous trail. It's not hard to track the Jackal (Bruce Willis) in the current incarnation, despite his showy wigs and accents. He leaves corpses splattered all over the place. Since he looms so large in the consciousness of half the world, the Jackal's ingenious techniques for staying invisible seem a tad superfluous. Inspector Clouseau couldn't miss him.

Gere plays Declan Mulqueen, an Irish Republican Army soldier sprung from prison by FBI man Carter Preston (Sidney Poitier) to help take out the Jackal before the Jackal takes out a prominent American political figure. Gere has personal reasons for wanting the Jackal caught, which means that Poitier gets to utter standard thriller warnings such as: "Don't make it personal." Gere, whose features are rather Slavic for an IRA gunman, has a good time bouncing off Poitier's bluster, and at moments he might be doing a good-humored sendup of Brad Pitt's idiotic Irish turn in The Devil's Own. One other performer walks boldly through this minefield of clichés: Diane Venora. As a disfigured Russian major, she speaks in low tones from a chest like a small tank, and her demented intensity blows everything else--including the Jackal, including his weaponry--off the screen.