Slate’s Best Books of 2015 coverage:

Monday: Overlooked books of 2015.

Tuesday: The best lines of 2015.

Wednesday: The best comics of 2015.

Thursday: Laura Miller and Katy Waldman’s favorite books of the year.

Friday: The best audiobooks of 2015.

***

Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story of books in 2015. No, that won’t work—in this age of diversity and abundance, there are too many parallel, conflicting, and overlapping narratives for one Muse to keep track of. My year in reading—doubtless different from your year in reading—had moments of buoyancy and whimsy as well as toughness and sorrow. It had liars and universal languages. And it began with delicious foods.

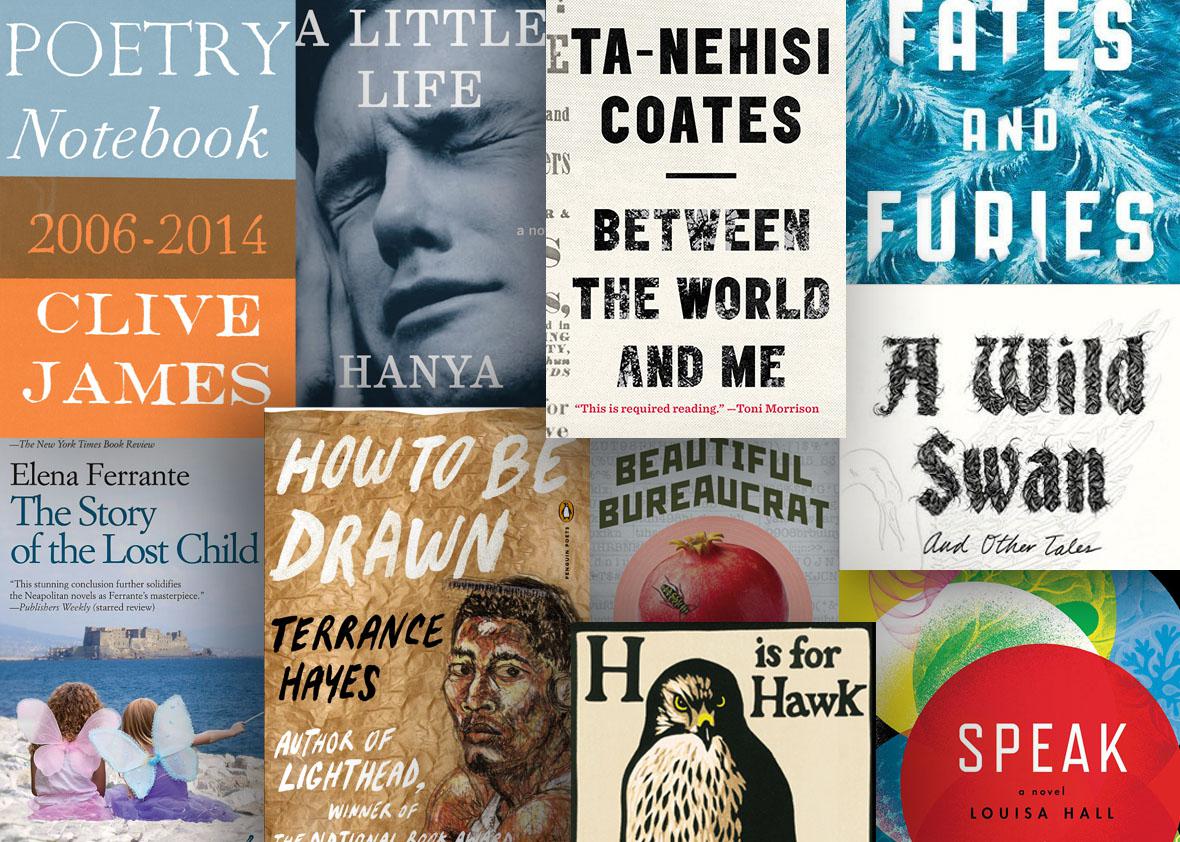

That’s Delicious Foods, by James Hannaham, one of several books this year to explore, unsparingly, Americans’ relationship to race. Hannaham’s horrifying and sonorant account of a widow and her son joins Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, Angela Flournoy’s The Turner House, Mat Johnson’s Loving Day, Tracy K. Smith’s Ordinary Light, Nell Zink’s Mislaid, and a rich slew of others in its attention not just to what seems irrevocable about blackness in the United States, but what seems fluid. Wesley Morris put his finger on the culture’s ambience of fluctuating identity in an essay for the New York Times Magazine. Rachel Dolezal, he writes, “represented—dementedly but also earnestly—a longing to transcend our historical past and racialized present.” Dolezal’s not the only one. According to Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose gorgeous letter to his teenage son turned “the Dream” and “the Struggle” into cultural touchstones in 2015, we are all telling ourselves the stories about race that we most want to hear. With Between the World and Me, Coates mingled memoir and criticism to remind the country of its history, despite his unwillingness to hope that such an education might bring about any kind of transformation.

Which brings us to the biggest books story of the year, Harper Lee’s shady “prequel” to To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus Is Racist. Actually titled Go Set a Watchman, the novel offered up a more complex Atticus Finch for our morally anxious times, yet contained him in a box not half as beautifully crafted. Watchman helped make 2015 an annum mirabile, a year of Lazarus Literature: long-lost works that rose from the mists of oblivion to find readers. Archivists surfaced a forgotten Fitzgerald story and a fresh Faulkner play; Dr. Seuss asked What Pet Should I Get from beyond the grave. As students debated scrubbing Woodrow Wilson’s name from the Princeton campus, we found reasons to interrogate our nostalgia and reassess our idols.

If both our identities and those of our sacred figures went undulating through 2015, maybe that explains the profusion of Big Twists in the year’s fiction. Some of the splashiest novels to soak the past 12 months involved a marriage that is not what it seems (Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies), a workplace that is not what it seems (Helen Phillips’ The Beautiful Bureaucrat) and a memory that is not what it seems (Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train). Groff and Phillips especially share a knack for fabular, dreamlike writing. Even as much of our subject matter stayed rooted in tough realities (death and destiny and prejudice), in 2015 we wanted extravagant and othering prose: prose that soared.

Ha, Laura Miller! I have to take a moment to gloat about my annexing H Is For Hawk for this list, though I know you wanted it for yours. (I hope letting you have Kelly Link’s great Get in Trouble helps.) The standout books of 2015 exhibited a lot of ambition, from the unselfconscious glories of Helen MacDonald’s language to the bifurcated structures of How to Be Both and Fates and Furies. And speaking of ambition, I couldn’t help including Hanya Yanagihara’s massive A Little Life (it’s actually a lot of life!) on my ballot. That grim and magnetic tome was this year’s answer to The Goldfinch, but bleak as a bedraggled crow in an oil slick.

Finally, I just want to note that 2015 was a banner year for short stories, from Link and Michael Cunningham to Edith Pearlman’s luscious Honeydew and Padgett Powell’s hilarious Cries for Help, not to mention collections from Steven Millhauser, Percival Everett, and Marian Thurm. We readers want the steak dinner—the 800 page gonzo novel—but we also want the buffet. Delicious foods indeed.

The Beautiful Bureaucrat by Helen Phillips. Henry Holt.

A gorgeously written and tonally slippery fable/myth/workplace drama about a new wife who finds a job typing strings of numbers into a mysterious Database. (Oh, is that your job too? Enjoy relating to protagonist Josephine Newbury, toiling under the watch of a faceless, genderless “Person with Bad Breath.”) When Josephine’s husband vanishes, she’s pulled deeper into the eerie inner workings of the institution. Meanwhile, connections surface between the digits she’s inputting and births, plane crashes, strokes. This deceptively slim (file-sized!) novel is terrifying and funny. It is also filled with wordplay: sounds and letters that recombine, appropriately enough, like living things.

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Spiegel & Grau.

An obvious choice, but Americans will be singing about this lucid and devastating manifesto on race, truth, self-deception, and fatherhood for years to come. Coates’ incandescent writing as he attempts to tell his teenage son what he knows almost obscures the grit and nuance of the argument—but here is a book that, when you engage deeply, leaves no certainty unchallenged, no solace untroubled. If you haven’t picked up a copy yet, go do that! It’s important.

Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff. Riverhead.

A Janus-headed portrait of a marriage that swings from the destiny-inflected narrative of golden boy Lancelot (called “Lotto”) to the shadow story of his quiet wife, Mathilde. He is naive and complacent, she withdrawn and angry. His guardian spirits are the Fates, hers the Furies. Groff’s are the Muses in all their epic and tragical glory.

H is for Hawk by Helen MacDonald. Grove Press.

Oh God. The last time I tried to write about this book, commenters got mad at me for disgorging “a vomitous outpouring of praise.” So I’ll keep it short. MacDonald weaves into her account of training a feral monster goshawk: the natural history of England, the biography of T.H. White, literary criticism, ghosts, angels, and refrigerated mouse parts. The result is unimaginably enlightening, provocative, and moving. Reeeeeaaaaad it.

How to Be Drawn by Terrance Hayes. Penguin.

A National Book Award finalist, this startling and musical collection of poems ranges from the museum to the street in its examination of blackness, masculinity, and art-making. Hayes is passionate, jokey, jazzy, and wrenching—the perfect Orpheus for our contemporary scene.

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara. Simon and Schuster.

Shudder all you want at the relentless sadism of Yanagihara’s “miserablist epic,” you still won’t be able to put it down. A Little Life—about four friends becoming themselves against a backdrop of horrifying abuse and assault—is singular not only in length, weight, and ambition, but in its resistance to narrative conventions like character growth and catharsis. You will encounter nothing like it all year.

Poetry Notebook: Reflections on the Intensity of Language by Clive James. Liveright.

Hurrah for the great Clive James and his criticism, at once crusty and sparkling, which reminds us how pleasurable it can be to befriend on the page someone garrulous, erudite, and exquisitely eloquent. No writer is more quotable than James, no muscle for poetic appreciation stronger than the one he’s honed over a 50-year career. As he continues his journey with leukemia, it’s worth noting the beautiful and complicated shadow he’s cast on English letters.

Speak by Louisa Hall. Ecco.

Five interlocking stories unfold around the central theme of artificial intelligence and its relationship to memory. A tech wunderkind goes to jail for building “illegally lifelike” robots; a Puritan teenager sails to the New World; a computer scientist surveys the wreckage of his marriage; Alan Turing writes to the mother of his best friend; a child mourns the loss of her robot and confidante. A poet by training, Hall cloaks questions of literary form in sci-fi zaniness. Her thoughtful, probing book is as emotionally complex as it is imaginative.

The Story of the Lost Child by Elena Ferrante. Europa Editions.

The vicious and brilliant Neapolitan series hurtles to its stormy end with this fourth novel, which sees Elena and Lila navigating the social and political upheavals of Italy in the 1960s and ’70s. Ferrante has never wavered in her depiction of two women, one all head and one all gut, inextricably linked. Her achievement is like Lila herself—“terrible, dazzling.”

A Wild Swan by Michael Cunningham. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Delicious, shivery, sophisticated fairy stories as spat from the pen of a Pulitzer Prize–winning author. “Most of us are safe,” Cunningham writes in his astonishing preface. “If you’re not a delirious dream the gods are having, if your beauty doesn’t trouble the constellations, nobody’s going to cast a spell on you.” But Cunningham will, and does. In a market oversaturated by reworked fairy tales, his are the best.

—

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.