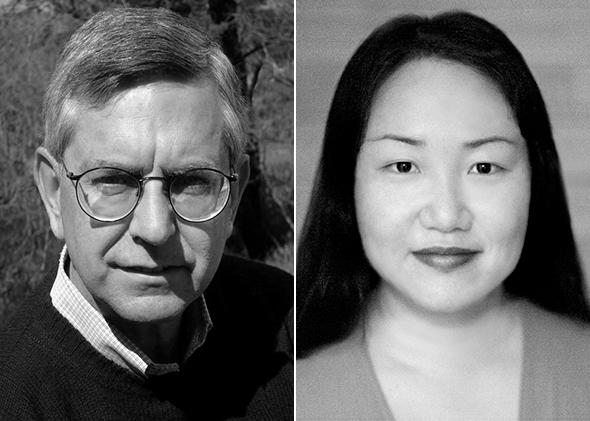

Hanya Yanagihara’s first novel, The People in the Trees—about a doctor in search of the secret to immortality—was published in 2013. Now Doubleday is releasing her second novel, A Little Life, which follows four friends in New York as they come of age together over the course of three decades. Yanagihara has done time on the other side of the author-editor relationship, too: She is editor at large for Condé Nast Traveler and previously worked at Vintage Books. So she and her editor Gerry Howard emailed each other about working with difficult writers, the difference between experienced editors and rookie editors, and A Little Life’s whopping length (more than 700 pages).

Gerry Howard: Your first novel was written sort of in secret over a decade. You don’t have an MFA and you don’t teach writing. Is it really just you and your imagination at work? Or do you have some support system I don’t know about?

Hanya Yanagihara: I do have the sense that, although there may be no one way to write a novel, there are many novelists who are in fact part of some sort of larger literary community, whether in the form of a writing group or an MFA program, to name two of the more common forms. But I think, traditionally, writers wrote alone. Or they had a single reader, often, famously, in the form of their spouse.

As punishing as it can be, however, I’d argue that there’s something precious about working alone, particularly when your career involves fixing other people’s language, as mine does, and as yours does, too. I started writing The People in the Trees when I was 21 and an assistant at Vintage, so this was probably 1996 or so. And you’re right, I didn’t tell anyone until 2007, and then only my best friend, Jared.

I think at first I didn’t tell anyone I was writing something because I found so tedious the people who did. In 1999, when I was working at my first magazine, Brill’s Content, there was an editor there who was forever printing out the manuscript of his work in progress (always, it seemed, when we were in the midst of closing the issue and needed the printer the most). There seemed to me something both admirably confident and, at the same time, shamefully arrogant about this: What gave this editor, gave anyone, the right to think that publication was owed them, that they could say so confidently that theirs was the work that deserved publication? And so my silence began, really, out of embarrassment, out of the intense desire to not want to be the sort of person who announced her hopes and ambitions to her peers.

But there was also something singular about not telling anyone what I was doing. … Once you show [the book] to another person, it becomes less and less yours, in a strange way. This is a necessary process of departure and distancing, but I think that until you know absolutely where you’re going with your creation, you have to keep it close. After you know for certain you can commit to living in this universe—and, more importantly, defend its particular logic—you can and should give it to someone to read. But I don’t think it’s necessary from the start.

All to say: Yes, it’s just me. For Trees, once I’d disclosed to Jared (and I thought of it that way—as a disclosure: This book’s existence was one of my longest-held secrets), I had him read each subsequent chapter as I finished it (I was about halfway through when I told him about it). For Life, he read each section as I completed it. After he did, he’d give me an immediate response—things he thought were working, concerns about logical lacunae, queries about dialogue, copy edits, notes on technical matters—and I’d respond with a list of about 12 to 20 follow-up questions, some of them broad in nature, others pointillist. He’d reply to those, and I’d incorporate the changes I wanted. Then he’d read the next section, and the process would repeat itself.

How do you prefer to work with writers? Do most things come into you the way mine do, as complete manuscripts?

Howard: Despite the fact that I am an only child and terminally involved in my own mental universe, I have somehow managed to train myself to be responsive to my authors and to tailor my responses to their needs—and, of course, to the requirements of the work being presented to me. Being married and responsible to another, much loved person, has certainly helped here. I like editing and enjoy the sense of creative collaboration it affords, but I don’t fetishize the process and am actually delighted when a book comes in and doesn’t need any fiddling. Don DeLillo’s Libra would be a conspicuous case in point, although that did require some delicate interventions of a legal nature. But I am in the quality control business, and if a draft or a partial manuscript is not working, however “working” is defined, it is my duty to say so to the author and to suggest, if possible, some ways that the book might be made to work. Sometimes I have to say, in the kindest yet firmest manner possible, that the writer is mining a dry or exhausted imaginative vein and it’s time to abandon the book and try something else. But usually the problems that present themselves are local and eminently fixable and I can provide some diagnostic insights and advice that prove practical and helpful.

(The one thing I’m not very good on is suggesting plot fixes. My mind doesn’t work that way. I am not a failed novelist; in point of fact I am a failed literary critic. I’d much rather have been Edmund Wilson than F. Scott Fitzgerald. Not that you asked.)

Yanagihara: “A failed literary critic”: what a relief. I honestly don’t know how the authors of people like David Ebershoff and Carole DeSanti—both excellent writers and excellent editors—do it. I’d be far too self-conscious and insecure if I suspected my editor might be a better novelist than I. They obviously tend to a heartier and more generous flock.

As an editor, I’ve always thought it wisest to follow the oath of “First, do no harm,” and I think the difference between an immature editor and an experienced one is that the former actually delights in a big, hot, steaming turd arriving at her desk. Or I used to, at least. When I was starting out in magazines, nothing seemed more excitingly self-punishing than reworking a disaster of a piece beyond recognition. As you get older, however, such experiences lose their thrill, as so they should—you realize that some pieces just arrive beautiful, and that you as an editor don’t need (to continue the scatological motif) to pee on it to make your mark. I still can, and do, overhaul when I need to, but the greatest lesson one learns as an editor is restraint.

Howard: In your case of course, the two novels we’ve worked on together came in as complete manuscripts and by and large the published versions of The People in the Trees and A Little Life do not differ. As you know, I initially found A Little Life so challenging and upsetting and long that I had to work my way through to appreciating it. It arrived on my desk at a time when my wife was going through a difficult health crisis and my soul was raw and troubled, and if ever a book was devised to trouble a soul, it is A Little Life. But the power of the thing was so undeniable that walking away from it was not something I could easily contemplate.

Yanagihara: What was the most challenging part of working on this book for you?

Howard: My first editorial concern with A Little Life was with its length, and my initial opinion was that it would be a better and/or more salable book if 100 or even 200 pages could go. But when I sat down with my pen in hand to edit it, I found that in fact the book justifies its length. So much happens to your four college friends who are the principal characters over such a long span of time that the book gains richness and amplitude as it accrues. (My private little descriptive tag for the book is “miserabilist epic.”) So I was wrong about that. Where you and I parted company was at the places where I felt that too much suffering was being piled onto your main character Jude, the orphan with the baroquely bad backstory, and also at times onto subsidiary characters.

Yanagihara: Now that I look back on it, I can see that most of your notes were of a fairly minor nature. At the time of their receipt, however, they felt insurmountable, epic, and assaultive. Part of this was their sheer physical manifestation: a 1,000-plus-page manuscript made literally shaggy with Post-it notes. I had to leave it under the bed for two weeks until I was ready to face it. Another thing I remember, keenly, is your admission that your first read took place during a very difficult period, when your wife was suffering a series of health problems—which makes it all the more remarkable that, even through many, many, many disagreements on all matter of things, I always knew you loved this book, and would always fight for its place and right to exist.

Loving a book is, as I can recall from my own brief stint in book publishing (and my longer one as a reader), a complicated and rewarding and sometimes punishing thing, as rare as it is heart-racing: You love it even when the writer is a huge pain in the ass. You love it when it’s unsalable.

Now that the book’s in print and I can’t change it, there are in fact things I wish I’d done differently in A Little Life—but they’re not the things I thought I might regret. One of those things I don’t regret is the amount of abuse Jude endures, which, as you say, was your major point of contention. But while you’re right that his level of suffering is extraordinary, it’s not, technically, implausible. (This is true of other aspects of the book as well: Could Jude be a litigator who specializes in both securities and big pharma? It’s unlikely. But it is possible.) Everything in this book is a little exaggerated: the horror, of course, but also the love. I wanted it to reach a level of truth by playing with the conventions of a fairy tale, and then veering those conventions off path. I wanted the experience of reading it to feel immersive by being slightly otherworldly, to not give the reader many contextual tethers to steady them.

Jared once called it an “emotional thriller,” and I think that’s right: the reader should, in part, experience the same terrifying unpredictability and uncontrollability of life, the helplessness of life, as Jude does.*

Howard: In some cases you trimmed things back a bit, but in others you stubbornly held your ground, and I respected that.

Where does that kind of confidence come from, anyway?

Yanagihara: I don’t know. Where does anything come from? I’ve always thought that one of the least successful encounters is meeting a writer one admires. For one thing, writers are generally much kinder, more empathetic, more generous people on the page than they are in person. For another, we tend to be dull, secretive, socially awkward, and likely to be taking notes on you to incorporate into our next work.

You, however, seem to genuinely enjoy authors: the people behind the writing, not just the writing itself. May I ask why? We once discussed whether writers were actually artists or not (I said no; you said yes), and while I’m not sure this is the forum to answer that question, I will say that handling authors is an often infuriating way to make your living and find fulfillment. As I recall from my book publishing years, I found most of them some combination of clueless, demanding, shrill (not a gender-loaded term: The men were as well), and myopic. Oh, and terrifically self-absorbed. All artists are, of course, but the problem with writers is that they can express themselves with words, and often do: long, wounded, self-pitying emails.

So what do you think—are there certain traits or characteristics that many writers share, and if so, is there a particular pleasure to be found in relating to this personality type?

Howard: Stipulate, as the lawyers say, that dealing with authors is not all beer and skittles, whatever skittles are, and further that there are some literary figures, who shall go unnamed here, who are really terrible people. In my own lucky experience I’ve had immense pleasure and satisfaction in working with the writers I’ve published across all forms and genres, and I don’t think that is just a fortunate coincidence.

At bottom and at heart I am a fanboy. Every English major’s dream job, etc., and I mean that. But beyond the matter of their care and feeding, writers are just damned interesting people to interact with and hang out with, you know? They are verbal and complicated and they know all manner of interesting things. Sometimes they even become your friends, although that is fraught with all kinds of peril. I should say, however, that I take a black box approach to the writers I work with, as in I try to avoid getting tangled up in matters of their creative psyche. I’m an editor, not a therapist; I deal with the results and not the process, and who wants to become all involved with transference anyway. When I find myself feeling that a particular writer is beginning to act a bit needy or demanding, which happens from time to time, I remind myself that I’m not the one cudgeling my brain on a daily basis to make something real and convincing and moving out of nothing, and on top of that trying to make a living out of that painful and terrifying process whereas I get a paycheck every two weeks and generous benefits.

Yanagihara: Don’t you think that the very profession of editing, especially fiction editing, slides quite quickly into therapy? This is not a culture that values writers in particular, so I think whenever they find someone who does—who takes them seriously, who takes their work seriously—there’s a sense of relief, as well as deliverance: Finally, someone who understands me. The unfortunate profferer of that understanding is in for a draining and intense ride. (Though I’ll take your word for it and concede that it can probably be rewarding as well.) Personally, I’d rather hang out with visual artists: They just see things so differently; they’re proof that the great questions about what it is to be alive, to be human (and all the littler questions as well), can be explored and answered with images, not words.

Howard: On occasion you can end up working with some of your heroes, and that can be a complicated thing. The aforementioned Don DeLillo, whom I regard as the greatest living American novelist, turned out to be a prince among men in every respect.

On the other hand I took over the Gore Vidal account just as he was entering his cranky phase, and sometimes when he was acting up or out I had to remind myself of the awe with which I regarded his essays and a handful of his novels. … He wasn’t such a good listener and didn’t take many of my suggestions.

Yanagihara: “Cranky phase”—ha! Wasn’t Gore Vidal’s entire literary life one brilliant, dazzling cranky phase? I’m afraid that very phrase shows just how incurably besotted with writers you are.

Howard: He remains, for all that, a hero of literature to me and I would not have missed being his dogsbody and whipping boy for the world.

As for you, you seem to write out of a powerful inner necessity and not any secondary impulse for fame or fortune, although I’m sure those things would be nice and I have a feeling they are coming. When and how did that inner necessity make itself felt to you? (So much for my black box …)

Yanagihara: You’re right—I’m not in it for the money or the fame. One seems impossible, the other seems undesirable. I guess I can only say that I only want to write something when I feel I have something urgent to say. It’s why I haven’t written a word since I turned in A Little Life to you, and why I can’t say with any certainty I’ll ever write another novel again. For one thing, the experience of writing this book was so depleting, so exhausting, so unexpectedly life-altering—as pretentious as that sounds—that I’m still extricating myself from its universe. (Every writer feels like Dr. Frankenstein, but I’ve been feeling so for longer than I anticipated.) For another, I feel this book contains everything I want to say at the moment about so many of the subjects I’ve thought about for so long: love, and friendship, and repair, and salvation. It may have only taken 18 months to physically write, but it took years of consideration prior to that.

Although I don’t believe that novels should be therapeutic, I can only hope that someone will read it and find that it says to them that it understands them, too. Of course I want it to be appreciated for its structure and pacing and show-offy technicalities, but the greatest accomplishment, for me, would be if someone finishes it and thinks, “That’s what I’ve always wanted to say—exactly.” If he does, I’ve done my job.

—

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara. Doubleday.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.

*Update, March 5, 2015: This post has been updated to include more of the conversation between Hanya Yanagihara and Gerry Howard. (Return.)