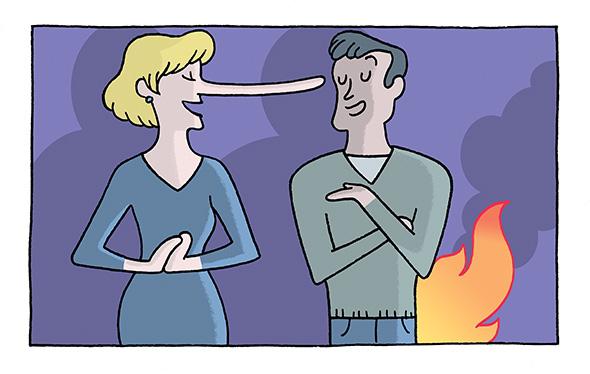

House was a great show, at least for the first few seasons. Hugh Laurie played a cantankerous drug addict doctor with near-mystical powers of diagnosis, powers whet on the stone of an infallible motto: “Everybody lies.”

House was a Mephistopheles figure, but he was telling the truth. A few pages into The Devil Wins, Dallas G. Denery II’s “history of lying from the garden of Eden to the Enlightenment,” we are presented with a study indicating that the average person composes three deceits for every 10 minutes of conversation—“and even more when we use email and text messaging.” Everybody lies. Diogenes the Cynic, lamp in hand under dazzling sunshine, patrolled the agora for evidence of one honest man. He found a bunch of guys who said they fit the bill, which is how he knew they didn’t.

Lying is fretted into human nature. But who put it there: God, the devil, or some natural law? When we lie, are we rejecting divine truth, adapting virtuously to the needs of the moment, making a necessary compromise? Or are we simply casting morally neutral word-feathers into the wind? The Devil Wins aims to upset a popular narrative among historians: that Western society became modern when people decided that lying was OK. In fact, Denery argues, there have always been voices for and against deception, from the time of Moses up until now. What changed was how those deceptions were understood: first as demonic devices, and then as secular inventions. It’s “as if, having lived too long in exile, we one day realized paradise had never existed in the first place,” Denery writes. The devil wins when he exits the stage only to reappear in the mirror.

Is it ever acceptable to lie? Denery examines the question from the perspective of five personas: Satan, God, a human being, a courtier, and a woman. The book spends a lot of time in Eden, going over and over the fatal exchange between the serpent and Eve, teasing out exactly how the one’s seductive sentences worked on the emotions, intellect, and pride of the other. What does a lie do? Denery asks, drawing on the writings of Augustine, Bonaventure, Luther, Calvin, and others. Can it transform the substance of your thoughts or only coax out potentials that are already present? Were Adam and Eve fallen before they tasted the fruit—did Satan just expose their charade?

Addressing these issues means picking over a somewhat inert mass of scholarly and religious minutiae, like whether the temptation occurred on the sixth or seventh day (if the latter, Adam would have more time to fall in love with Eve) and what Eve intended when she told the snake that “perhaps” transgressing God’s command would lead to death. The hair-splitting can, no lie, feel awfully pedantic. Still, Denery weaves a convincing account of the Fall as a metaphor for all subsequent misinterpretations of God’s word, all instances of humans contorting Scripture into the shape of their desires. I was moved by his small addition to the skein of commentary: Noting that Eve appends to the divine prohibition an extra clause—she and Adam aren’t even allowed to touch the Tree of Knowledge, she tells the serpent, though God only ever mentions eating—Denery discovers in the act of lying an unexpected poignancy. Eve yearns for “something more,” he claims. Some “secret reservoir of knowledge” or hidden mystery. She wants to embellish the manifest truth with a little extra—and though her elaboration on divine speech is prideful, it also reveals a creative yearning, a human wish for things to be greater than they are.

So there’s a proleptic shadow on Eve’s lie, something heartsore that points at the brokenness or inadequacy of the world-as-is. In The Devil Wins, deceit becomes not just an effluence of our sinful natures but a response to the loss of paradise, an effort to rebuild the dream. Adam and Eve wear sneaky fig leaves to hide their shame; they want to be pure again, even if they can’t. This ambivalence energizes the book, transforming its dry citations into a debate worth following: Are lies a disease or a symptom, a problem or a makeshift solution?

From Satan, father of lies, Denery then turns to God, wellspring and arbiter of truth. Philosophers like Descartes, equating falsity with imperfection, denied that God was capable of saying a mendacious word. But God fibs his way through the Bible, and Jesus is worse—like the lion in medieval bestiaries, sweeping away his tracks with his tail, the son comes to earth and immediately conceals his divine nature. “Noble dissimulation!” cried the theologians. Jesus’ sacred ruse was a “mousetrap” for the devil, who snapped at the bait only to forfeit his ownership of humanity. Denery uses his God chapter to pivot into more nuanced territory: prudent stratagems and healthy illusions. Christ’s generative lie is categorically different from our fallen bullshit, he concedes. Can humans, too, learn to bend the truth in a wise and useful way?

Here’s where the book gets funny, shuffling through various 13th-century attempts to salvage dishonesty: equivocation, mental reservation, amphibology. These are all not-lies that not-liars tell when they would like to dupe the world without breaking any religious interdictions. An equivocator, for instance, “takes advantage of words with multiple meanings,” such that “if asked by persecutors whether a man they intend to kill passed this way,” he might reply, “He did not pass here,” with “here” signifying “the very spot on which we stand.” A mental reservationist deceives by omission, by withholding the facts he knows. (“Who ate the last holy wafer?” [Silence.]) Amphibology posits that there are many different kinds of language, “purely mental, purely vocal, purely written and a mixture of these,” all of which blend together to produce a true or false statement. Thus, “if a friend asks us for money or for a book, we are free to respond ‘I don’t have it’ even if we do, so long as we silently add, ‘such that I would give it to you,’ ” Denery explains helpfully. Sounds like a brilliant fix (for sophistic psychopaths)!

Photo by L. Fleming

Of course, the theologians who advocated amphibology operated from a religious framework that feels remote to us now. To worry over whether you’d deceived someone missed the point, which was that false language offended against creation, the arrangement of things in their right and perfect order. But while the church fathers equivocated, secular society was dreaming up a new definition of mendacity, one that tallied its wrongs against other people. This, Denery points out, gave liars some flexibility: They could perhaps justify their perjuries with a crop of favorable outcomes—not just for their neighbors, but for themselves too. Enter the courtier, voice four in the quintet, who bequeaths the lie to the early modern nation-state. Where ambitious aristocrats waltzed with care around the throne, flattery and illusion were survival mechanisms, as Darwinian as the cedar coloring on a moth’s wings. Sometimes, lies precluded worse crimes. “The sinews of the Leviathan’s loins are entangled,” wrote one medieval canon lawyer, “and the purpose of his suggestions is entangled with tangled devices. Thus, many commit sins because hoping to avoid one, they cannot escape the snare of another.” Deceit starts to look a lot like a precondition for social harmony. We are so gross, so selfish and vain; we’d never tolerate each other outside of the collective churn of our agreeable facades.

But I want to get to my favorite part of The Devil Wins, which is Denery’s chapter on those inveterate liars, women. Essentially, this strand in the fugue is a collation of the most deliriously nutso misogynist fumigations you will ever read, a cascade of faux-biological explanations for feminine evil and fallaciousness through the ages. Such as: “They are made of bone, while our bodies are fashioned of clay; bone makes more noise than clay. … It is their nature that makes them foolish and proud” (Jehan le Fevre). Or: “Heat purifies and invigorates the man’s semen, transforming it into an active, creative, and ensouling principle. Women … being cooler, their semen is less refined, passive rather than active, the mere material on which the male principle operates … their bodies and intellectual abilities [are] less developed” (Aristotle, paraphrased by Denery). Or: “They are so full of venom in the time of their menstruation that they poison animals by their glance; they infect children in the cradle; they spot the cleanest mirror and whenever men have sexual intercourse with them they are made leprous and sometimes cancerous” (Albert the Great, in his own words). The chapter goes on to unfold the perceived connection between female loveliness and artifice, between Eve and her spiritual daughters, between the lie that tempts the intellect and the womanly shape that beguiles the flesh. And—crucially—it gives fair time to educated noblewomen like Christine de Pizan and Lucrezia Marinella, who in their work exposed the misogynist creed for the veil of lies it was.

But these nuggets of interest are too often buried in starchy erudition that doesn’t do justice to the topic’s seductiveness. Alas, when all is said, and said again, and said again in a slightly different way, and done, The Devil Wins will delight academics and historians a lot more than it will enlighten lay readers. You want to learn about lies? Go to Netflix and stream House.

—

The Devil Wins: A History of Lying From the Garden of Eden to the Enlightenment by Dallas G. Denery II. Princeton University Press.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.