Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

The Voice of the Poets

The life and work of an audiobook narrator.

Illustration by Danica Novgorodoff

Listen to the conversation between author Bruce Holsinger and audiobook narrator Simon Vance by clicking on the player below:

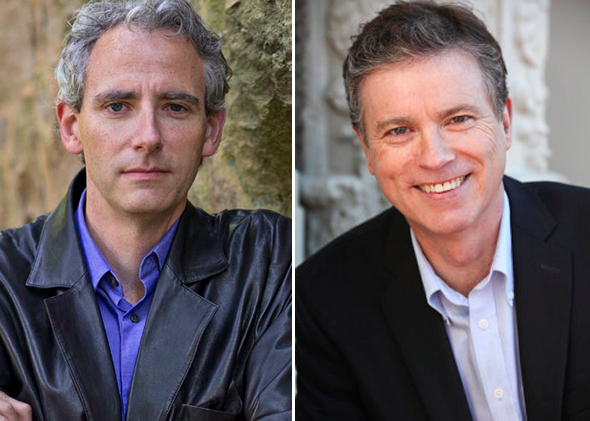

Bruce Holsinger, who teaches medieval literature at the University of Virginia, is the author of A Burnable Book, a debut historical thriller set in Chaucer’s England, out now from HarperCollins/William Morrow. The audiobook is narrated by Simon Vance. Neil Gaiman has called Vance "the gold standard of narrators," while Hilary Mantel writes of his recording of Bring Up the Bodies, "As if by telepathy, he has preserved the rhythm of the text as I heard it when I wrote it." In this conversation, the novelist invites his narrator to discuss sound, voice, and sense in historical fiction, as well as the unique role of audiobooks in bringing fiction to life.

Bruce Holsinger: Simon, you’ve recorded audiobooks for some of the world’s most admired and influential authorial voices across genres and modes: Hilary Mantel, Amitav Ghosh, Anne Rice, Roberto Bolaño. And you’ve also brought literary history to audible life through your recordings of Trollope, Dostoyevsky, Dickens, Bram Stoker, and the list goes on. Listening to your recording of my novel, A Burnable Book, has been a truly transformative experience for me. I only wish I’d been able to hear the story in your voice before submitting a final draft of the book, as your reading helped me hear and see things I hadn’t noticed before and might have decided to push in different directions. But what has your own experience as a narrator taught you about literature? Are there things we can get out of an audiobook that we can’t experience through silent reading?

Courtesy of Daniel Addison and Cynthia Smalley

Simon Vance: There is still a divide between those who think audiobooks are “cheating” and those who swear by them—but I think the distance between those factions is narrowing. I have total respect for people who enjoy the feel of the book (or tablet!) in their hands and the ability to interpret the author’s words in their own way. But I also think it’s possible to view the audiobook as an artistic endeavor in its own right. Many people read to themselves so fast—sometimes scanning the page in apparent moments of not-much-going-on to get to the next bit of action—that the audiobook listening experience can actually be richer for the way it forces one to listen to the book at a narrator’s pace. I have been told so many times by people who have read a book and then listened to my narration of it that they find so many levels they hadn’t realized were there. There is also the need to understand the written text, and here an “educated” narrator can help enormously: I think there’s a large population of people with little time for the sentence structure and archaic grammatical styles used in, say, Trollope. When the work of clarifying the meaning is already done by the narrator, these reader-listeners find a whole new level of enjoyment in those texts.

Holsinger: I imagine historical fiction represents a particular challenge in your line of work. Do you ever develop what you think of as a “period voice”? When narrating Bring Up the Bodies, for example, was there a Reformation voice you tried to invent? Or is voice more determined by the idiosyncrasies of character?

Vance: Definitely the latter. Mantel writes her characters in a contemporary style—they are not prancing about saying “forsooth,” they are talking in a way you or I might (if you or I happened to be a servant of the king). I am not going to research how a mid-16th century landowner might sound, but I am going to give some sense of the class of that character in a way that might identify them as such today. I am aware of some of the changes in vowel sounds over the centuries in British society, but I don’t want to throw up too many extra bells and whistles that will have a listener thinking, “Oh, that’s a very authentic accent,” instead of enjoying what the author is getting across. I will generally contemporaneanize (is that a word?) the dialogue in the same manner that I might give everyone in a book set in, say, Sweden, British-class accents rather than have them all talk like the Swedish Chef …

Holsinger: Ah, the Swedish Chef—one of my own favorite voices, and one my sister and I mimicked excessively when we were kids! So what are some of the most challenging historical voices you’ve narrated in your career, whether from contemporary historical fiction or 19th-century novels?

Vance: I had a huge temptation to give Mantel’s Henry VIII a magnificent British regal voice in the manner of, say, Richard Burton. But Henry actually was ridiculed (in private, of course) for having a rather high-pitched tone, and Mantel mentions this in the novel. So I had to find something that was distinctive enough to be ridiculed by other characters but still not sound cartoonish. I have had nothing but fun creating the voices of Dickens’ and Trollope’s characters. I am an actor, and I rely on my instincts much of the time. I don’t always plan how these people are going to sound. I often absorb who they are and see what comes out when I open my mouth. (Of course, then I have to remain consistent throughout the book.)

Holsinger: Though the voices of characters aren’t the only or even the primary voices you’re responsible for creating, are they? You also have to voice the narrator, and your voice becomes the way listener-readers will experience the landscape, the visual culture of fictional worlds, and the details of everyday life like food, clothing, and so on. In effect you’re creating a complete soundscape for every novel you narrate.

Vance: Indeed, but the work has already been done by the author—I just need to “plug in” to that world, or style, and allow what follows to come naturally. I think it’s a misunderstanding that an actor has to do something to bring a character (or story) to life. No. The skill of acting is in the work beforehand that allows you to absorb the material fully such that you can be open to the influences of whoever has written the piece you are performing—whether on stage, screen, or in an audiobook.

Holsinger: You began your audiobook career recording for the Royal National Institute of Blind People and its Talking Book service. The protagonist of A Burnable Book, John Gower, is starting to lose his vision at the time the story is set, and we know historically that Gower was effectively blind late in his career, when he wrote some of his most arresting poetry—so I’ve been interested in these connections between blindness at the levels of story and sound, and as the Gower series goes on this will become more and more of a theme. Do you imagine a blind audience when you record? Is there a special affinity between audiobook narrators and the blind, who benefit from your work?

Vance: Many of my generation of audiobook narrators began by recording books intended primarily for the blind or partially sighted, and it certainly helps to focus the mind on what exactly it is that we are doing. In a sense I am always reading for the blind. The only goal in my mind is to give my listener the same mind pictures that the author experienced in creating the book in the first place.

Holsinger: The notion of “mind pictures” you’ve suggested is a helpful one, and in fact it’s a very medieval idea that you often find in discussions of memory in the Middle Ages: The mind must create pictures, the more vivid the better, in order to retain and recall the information being stored. I suppose writing is a bit like that, in that an author is drawing on a kind of pictorial reservoir rather than simply a verbal one, and I think soundscapes are also part of this process of invention.

Vance: Although your book is fictional, it is based on certain truths that you must have uncovered about society at the time. Unlike, say, an author of the kind of historical fiction that deals with wizards and dragons, I wonder if you feel an added pressure to get the facts right about the little things in the world of A Burnable Book.

Holsinger: That’s a question that all writers of historical fiction wrestle with in various ways. As I’ve taught historical fiction, I’ve realized that there’s a spectrum of approaches to issues of authenticity and so on, and differing degrees of asceticism or strictness about facts and details. Put a zipper on a medieval bodice, and your novel will be thrown across the room! There’s a whole gleeful genre of anachronism-hunting among readers and even authors of historical fiction that can be quite intimidating for new writers in this mode. I suppose the research has come more naturally to me given my academic work in medieval studies, and I knew a lot of general information about the period going in, of course. But what really surprised and in fact delighted me was my ignorance about a lot of the details of daily life: what a middle-class woman in medieval England would eat for breakfast, for example, or what sorts of items you’d find in a kitchen.

Vance: I particularly enjoyed the process of discovery that came with the part of the story told in installments taken from a letter. These episodes recur all the way through the novel. They’re written in a woman’s voice (though that’s not clear at the start), and it was quite an emotional story, especially toward the end, which made it perhaps the most challenging and yet satisfying part of my own journey as the novel’s narrator.

Holsinger: I’m glad to hear you say that. The internal letter—the story-within-the-story, I suppose you could call it—is one of the shortest parts of the book, just a few thousand words altogether. Yet it also contains the secret to the story as a whole, explaining the background of the manuscript (the “burnable book”) and the emotional investment it inspires on the part of the characters. Originally I wrote this internal narrative as a new Canterbury tale, complete with a prologue in decasyllabic couplets, imagining Chaucer writing it all up after the fact, but I ended up with the simpler solution of embedding it as a letter that tells the crucial backstory. One thing I really loved about your reading of the letter is the distinctive inflections you give to the mysterious narrator’s voice: the high pitch, the slight and indeterminate accent, the moments of hesitation that make us think about what we’ve just heard and learned. It creates just the kind of sonorous atmosphere I heard as I wrote those sequences. So thank you, Simon.

Vance: And thank you for inviting me to join you. John Gower was great company!

---

A Burnable Book by John Holsinger. Read by Simon Vance. Audible.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.