Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

I Was Burning

Sarah Schulman’s landmark lesbian novel of grief and rage, 25 years later.

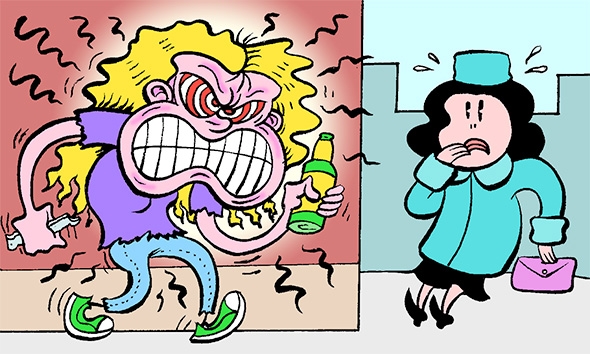

Illustration by Peter Bagge

In 1988 I was living 3,000 miles from my family. We spoke on the telephone once a week, but we didn’t see each other for years at a stretch. We weren’t estranged so much as strange to each other; my gayness was just one more thing we didn’t have in common, yet another topic we didn’t discuss. At the time, the distance between us didn’t even seem peculiar. Among my peers, PFLAG parents were the exception. Coming out was often met with threats of expulsion from the family or worse. I had friends who were institutionalized and knew at least one man whose parents put ground glass in his food when he told them he was gay.

Everyone figured their folks would eventually come around, and most did—even if they always seemed more invested in the lives of their heterosexual offspring. Still, knowing you’re a disappointment at best takes a toll. That year, Sarah Schulman explored the damage families inflict on their LGBT members in After Delores, now freshly re-released in a 25th anniversary edition by Arsenal Pulp Press.

In the novel’s first six pages, the lone wolf of a narrator gets drunk, makes out with a girl, obsesses about her ex-girlfriend, and acquires a gun. It’s an astonishingly efficient establishment of themes, because considerations of booze, sex, violence, and abandonment dominate the rest of the book. There’s a plot of sorts—while nursing some serious ill will against her ex-girlfriend Delores, the narrator tries to figure out who killed go-go dancer Punkette—but it’s a mystery novel only in the loosest sense of the term. Our nameless narrator is no private dick, and her drunken meanderings around New York City barely qualify as an investigation. But she does want justice for Punkette. Somebody has to hold society accountable for her murder, and who better than an unstable outcast?

The cover of the new edition features an unmade bed—a bed the narrator can no longer bear to sleep in after Delores takes off, abandoning their shared Lower East Side walkup so that she can trade up to fashion photographer Mary Sunshine’s Tribeca loft. There was no good reason for Delores to leave—no rational explanation for the narrator to go from being “the person Delores cared about the most [to] the one she most wants to break,” except perhaps her refusal to lie and promise that they’d never break up. “I couldn’t say ‘forever’ unless I knew for sure it was true,” she declares, while Delores’ new girlfriend, Sunshine, said “forever” without a second thought.

Without a good explanation for the terrible treatment Delores meted out to her, the narrator loses her grip, first on her drinking and then on her impulse control. “If I had money, I would have gone to a decent psychiatric hospital,” she says, “but instead I was just another pathetic person on the Lower East Side.” A pathetic person with serious anger issues. As soon as she lays hands on that pearl-handled pistol, she fantasizes about using it to shoot Delores and dreams of cutting Sunshine’s face open with a can opener.

Those violent impulses were always disturbing. When After Delores first appeared, it was one of the first openly lesbian modern novels to be published by a mainstream press. Although the details are now lost in the pre-Internet haze, I remember feminist reviewers observing a pattern in the few lesbian books that caught the eye of big New York publishers: They were all shot through with violence. There was this one, Dorothy Allison’s Bastard out of Carolina (which by no means valorizes the sadism it describes), and at least one other novel whose title I’ve now forgotten, even though I remember once reviewing it. All that violence was undoubtedly present, but with the benefit of hindsight, I now realize it wasn’t that mainstream publishers were seeking savage thrills; it was that lesbian writers needed to express their rage.

In a new introduction, Schulman claims that in writing After Delores, she was “escaping from the tyranny of positive images that had started to dominate grassroots feminist publishing at the time.” In 1988 the notion of a “tyranny of positive images” would have struck me as completely upside-down—like many others, I was convinced that positive images were a necessary corrective to decades of negative portrayals of lesbians in literature. Now I know that anger can be an appropriate response to exploitation and abuse, and besides, there’s a difference between fantasizing about assaulting someone and actually committing the act. About three-quarters of the way through After Delores, the narrator receives a visit from a trio of vigilantes who accuse her of having committed an act of violence against women when she sent a postcard to her ex bearing the message, “I hate you Delores. I walk down the street dreaming of smashing your face with a hammer.” She points out the difference: “I didn’t say I would smash her face with a hammer, I said I wanted to. It’s not the same thing.”

Back then, I saw the narrator’s urge to smash someone in the face as a sign of her brokenness; now she seems like the only one whose moral compass is intact. It’s not that she’s messed up; it’s that the rest of the world isn’t meeting its responsibilities. As she tells her friend Coco Flores, “Some things are just too outrageous to let them go by.” Punkette deserves justice, and no one else in the entire city of New York cares enough to look for her killer. The narrator deserves love and loyalty, but no one is willing to give her those things, or even to use her name.

Nayland Blake

Schulman has returned to the cruelty of abandonment by those who are supposed to love us unconditionally many times since, most notably in 2009’s Ties That Bind: Familial Homophobia and Its Consequences. But even in the middle of the AIDS crisis—when thousands were rejected by their families when they needed them most—her desperate, damaged heroine called out a crime many of us then accepted as our due. When I first read After Delores in 1988, familial rejection was such a common component of LGBT life that I’m pretty sure I didn’t even pick up on Schulman’s point, as undeniable as it is: Abandoning children because they’re gay—which is to say, for no good reason—hurts them, and it damages the rest of society even more. After nonconsensual sex with a lesbian named Charlotte, the narrator has an epiphany: “I could see everything. I was burning. I could see that there was so much more pain than I had ever imagined and I didn’t have to look for it. Those closest to me would bring it with them.”

A special kind of import attaches itself to a book whose cover announces that it’s a “25th Anniversary Edition.” It inevitably becomes a symbol of the year it was released, the epitome of 1988-ness. The New York of a quarter-century ago was a city full of danger and despair, but After Delores reminds us that the homes we left to find refuge there and in other cities like it were infinitely more hazardous to our health.

---

After Delores by Sarah Schulman. Arsenal Pulp Press.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.