Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

Donna Tartt and Michael Pietsch

The Slate Book Review author-editor conversation.

Beowulf Sheehan / Deborah Feingold

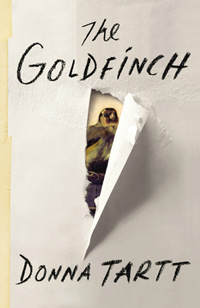

Michael Pietsch, now CEO of the Hachette Book Group, acquired the book that would become Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch in 2008, when he was the publisher of Little, Brown. The Goldfinch marks Pietsch and Tartt’s first book together, after her previous novels The Secret History and The Little Friend were published by Knopf. In this conversation, the novelist and her editor discuss the author-editor relationship, the danger of talking about books before they’re finished, and the “philippic against standardization” Tartt sent her copy editor.

Michael Pietsch: What expectations did you bring to working with an editor on The Secret History?

Donna Tartt: Quite honestly I was frightened and suspicious. I'd been assured, at age 21 or so, by a well-known editor who saw the first part of The Secret History in what was basically its final form, that it would never be published because "no woman has ever written a successful novel from a male point of view." Then too, it was the age of Raymond Carver and minimalism. The Secret History was highly unfashionable, in terms of both style and subject matter. So, even though the novel had received warm support from early readers like Joe McGinnis and Arturo Vivante and Bret Ellis, I was afraid that whoever bought it was going to want to carve it down into something that was more like other literary debuts being published at the time. Happily Gary Fisketjon appreciated The Secret History on its own terms and didn't try to re-mold it into something it wasn't. He's a very hands-on editor but at the same time he really does want you to do what you want to do.

What about you? Tell me about the first book you edited.

Pietsch: Ha! It was a work of medical instruction that had been through two edits before it was given to me. I was nearly fired for my entire lack of understanding of how much work goes into writing a book and how sensitive the writer might be about the tenor of a recent college graduate’s pedantic suggestions. Fortunately I survived to sharpen my pencil another day.

Tartt: Do you work with all writers the way you work with me? (Which is to say, not really commenting until you have the whole manuscript in hand.) Or is it different with different writers?

Pietsch: Every book is different and the editor’s job is always the same: to work with the writer in the way they want to be supported, to understand as well as possible what it is the writer has set out to do, and to point out any places where the editor believes that the author has not lived up to the expectations they have created. It’s an intimate process, and an extraordinary trust to be allowed to see a writer’s work before it goes out into the world.

Every edit is different. Some writers like to show a chapter at a time or even individual scenes, as they go, for comment; I’ve worked with writers who wanted to read a passage over the phone just after they completed it. Others want to write in total privacy, not revealing a single thing until it’s finished. Sometimes editing consists primarily of a letter asking questions about plot elements, or about pacing, or character, and sometimes it’s entirely line-by-line comments on language. I love Nabokov’s Paris Review interview where he describes hurling down “thunderous stets” in response to “suggestions.” Editing is only useful if the writer finds it to be. And some writers really don’t want an editor’s help at all. Martin Amis told me once that he’d rather have his own mistakes than an editor’s fixes—an opinion that any writer is entitled to!

Tartt: I'm with Martin Amis on that. I'd always rather stand or fall on my own mistakes. There's nothing worse than looking back, in a published book, at a line edit or a copy edit that you felt queasy about and didn't want to take, but took anyway. But then again: There's nothing like having a sympathetic reader who asks the right questions, who understands what you're trying to achieve and only wants to make it better. The best fixes are seamless—solutions that are in plain sight but you haven't seen yourself, that someone else has to point out to you.

Pietsch: The editor works in disappearing ink. If a writer takes a suggestion, it becomes part of her creation. If not, it never happened. The editor’s work is and always should be invisible.

Most writers I know have more than one editor, beyond the one who works for the publishing company that has invested in their book—a small cadre whose advice on the manuscript they solicit and listen to. Do you have such a group?

Tartt: No not a group, though I have one or two people whose opinion I trust. It's important—especially in the excruciating middle stage of writing a book, and especially when you write books which take as long to write as I do—to have someone who will tell you midstream the rough truth about whether something works, or doesn't. But I don't show unpublished work around a lot. At school, my earliest and most crucial readers were really just that—readers. They were enthusiastic, they encouraged me, but didn't supply a lot of direction or criticism. I felt that it was enough just to interest readers on the most basic level—I knew that I was on track as long as people stayed interested in the story and kept asking: "Where's the next chapter of your book?"

Do you ever have people showing you very rough drafts? Or running the idea of a book by you before they start writing it? I often long to talk out a book informally, in the beginning stages, before I begin to write—to feel my way towards my story by talking it out to a sympathetic listener—but there's always the danger of talking the book away. Or, of becoming discouraged by one's own ill-formed ideas, poorly expressed.

Pietsch: I don’t see many very rough drafts. Sometimes a writer will talk about a plot idea. Michael Connelly told me his idea for The Lincoln Lawyer’s main character years before he found the story that made the character work.

Tartt: Did he talk about the character as character? Was he trying his way to find a story by talking about the character? That's exactly what I mean, when I say I think it might sometimes be helpful, early on, to talk about an idea or a story before it's committed to paper, before one even starts to write.

Pietsch: Michael was telling me about an idea he had for writing a legal thriller, featuring this unusual kind of lawyer unique to L.A., one whose office is in the back of a car because he needs to get to so many far-flung courthouses. All I could say at the time was: “That sounds great!” The character embodied the place. And writing legal thrillers, in addition to his great police detective thrillers, seemed well worth trying for a writer of his talent

Sometimes a writer will show me a big section early on, to get a sense of how I think the story is going.

Tartt: For me—showing a half-finished manuscript is tricky. Just as a bird will get spooked and abandon her eggs if some outside party comes around and makes too much noise or pokes around the nest too intrusively—well, that's what it's like for me if I show work too early and I get a lot of editorial suggestions at the wrong time. Even if you need, and want, a second opinion, it can be dangerous to have people telling you what they think you ought to add, or cut, before you've even finished telling your story. One loses heart; one loses energy and interest. Or at least I do.

Pietsch: It’s hard to give a response to a partial manuscript. You can’t know what secrets the writer is layering into the early chapters. You may be confused about something, but the writer may intend that confusion. All the editor can do is say what parts you’re enjoying and why, point out any places where it feels slow, and what parts if any feel confusing.

Tartt: With a partial manuscript, I think it's especially important for an editor to say what he's enjoying. For a novelist to be told, midstream, what he's doing right can actually influence the unwritten parts of a novel in a positive way—praise helps a writer know what's good about what he's written, what's interesting and exciting, and what to work for in writing the conclusion. Knowing the strong points focuses one's attention on what's strong, and makes it easier to move from strength to strength. Whereas criticism at the wrong time, even if it's legitimate criticism, can be seriously damaging and make the writer lose faith in what he's doing. It's the timing that's all-important.

Pietsch: Before I began editing your book, you sent a philippic against standardization. You declared that spell-check, auto-correct, and (if I recall correctly) even sacred cows like Strunk & White and the Chicago Manual of Style are the writer’s enemies, that the writer’s voice and choice are the highest standard. Do you have advice for other writers confronted with editorial standardization?

Tartt: Was it really a philippic? I thought it was more a cordial memorandum.

Pietsch: Two-thirds of the way through a set of notes to the copy editor, you wrote:

I am terribly troubled by the ever-growing tendency to standardized and prescriptive usage, and I think that the Twentieth century, American-invented conventions of House Rules and House Style, to say nothing of automatic computer functions like Spellcheck and AutoCorrect, have exacted an abrasive, narrowing, and destructive effect on the way writers use language and ultimately on the language itself. Journalism and newspaper writing are one thing; House Style indubitably very valuable there; but as a literary novelist who writes by hand, in a notebook, I want to be able to use language for texture and I've intentionally employed a looser, pre-twentieth century model rather than running my work through any one House Style mill.

Tartt: Well—I'm not saying that the writer's voice is always the highest standard; only that a lot of writers who are fine stylists and whose work I love wouldn't make it past a contemporary copy editor armed with the Chicago Manual, including some of the greatest writers and stylists of the 19th and 20th century. It's not as if we're the French, with the Academy, striving to keep the language pure—fine to correct honest mistakes, but quite apart from questions of punctuation and grammar—of using punctuation and grammar for cadence—English is such a powerful and widely spoken language precisely because it's so flexible, and capacious: a catchall hybrid that absorbs and incorporates everything it comes into contact with. Lexical variety, eccentric constructions and punctuation, variant spellings, archaisms, the ability to pile clause on clause, the effortless incorporation of words from other languages: flexibility, and inclusiveness, is what makes English great; and diversity is what keeps it healthy and growing, exuberantly regenerating itself with rich new forms and usages. Shakespearean words, foreign words, slang and dialect and made-up phrases from kids on the street corner: English has room for them all. And writers—not just literary writers, but popular writers as well—breathe air into English and keep it lively by making it their own, not by adhering to some style manual that gets handed out to college Freshmen in a composition class. There's your philippic, I guess.

One final question for you: How much of your job is actually editing? Is it the most important part?

Pietsch: The editor’s job has always been a combination of elements, of which actual editing is just one part. The first thing an editor is is an investor: They are trusted by their company’s owners to invest their money in writers. They are publicists for their company and themselves, getting authors and agents to submit great books to them for publication. They are negotiators, working to arrive at contract terms that will, if all goes well, enable their company to make a profit selling the book.

The editor is the first point of contact the publishing company has with the writer, and often the closest relationship, and the core of that relationship is the work of editing. The writer trusts the book to the editor, to read before others and perhaps suggest improvements. If the writer values that advice, the bond can become deep and long-lasting. So after good judgment about what books are worth investing in, editorial skill is the editor’s most important qualification.

In modern publishing, as the business has grown in sophistication, size, and complexity, the editor's other big role has gotten bigger. That is, the editor as product manager—the person who knows the entire length and breadth of the business and can communicate all that complexity to the author and agent at the same time that he represents the author’s work within the company. This is the part of the job that takes up all the time: working with the writer, the publishing company, and the world outside on things like title, subtitle, timing, pricing, positioning, cover art, type design, selling copy, publicity strategy, marketing approach, budgeting, and all-round enthusiasm spreading. So to edit a book is to work on all this and much more, for many books at once at different stages in those books’ lives.

But like editing, all that work is invisible in the long run. The thing that lasts, the miracle at the center of it all, is the string of words that a writer has strung. That's it.

---

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt. Little, Brown.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.