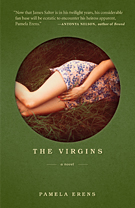

Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

Pure as the Driven Snow

Pamela Erens’ The Virgins and the creepy narrator who remembers them.

Illustration by Dalton Rose

There is a moment in Pamela Erens’ second novel, The Virgins, in which two boarding school kids look out onto a private field in winter. The snow all around the field is “thickly cratered with footprints that cross this way and that and fall into each other,” but the snow on the field itself is unsullied. It is 1979, in that giddy sliver of exploration after the sexual revolution and before the rise of AIDS. The girl is 16. She turns, closes her eyes and falls backward into the field. The boy is there to catch her.

The Virgins is, before anything else, a tragedy. The reality of losing your virginity cannot compare to all the metaphors. If you find yourself in an exquisitely lovely, untouched field with your beloved, you should probably run away.

At least that seems to be the jaded perspective of Erens’ narrator-villain, Bruce Bennett-Jones, a third-generation Auburn graduate half-recalling and half-imagining the high school romance between two of his classmates, Aviva Rossner and Seung Jung. Bruce cops to “sourness” as his defining trait, though there are so many more to choose from: prurience, jealousy, cruelty, loneliness, self-loathing, self-pity. He’s a storyteller, a lover of ancient tragedies and Greek myths. Early on, he tries to rape Aviva in an abandoned boathouse. It is after she shuts him down that he retreats into voyeurism and fantasy, though his obsession never wavers. He speaks from some time in his adult future, in tones of alternating lasciviousness and regret. “I … see my tale as a kind of restitution,” he says. Often, it feels more like an attempt to repossess the girl who got away.

The virgins themselves are tender, flawed, and very likeable. Aviva, a tightly wound Jewish girl from an unhappy family, meets Seung, the laid-back son of Korean immigrants, in music theory class. (Or so Bennett-Jones relates; it’s clear from the beginning he’s an unreliable narrator.) Their liaison is highly visible on a Northeastern campus in the 1970s, though few of their classmates know that their dalliances—“hours of leisurely pleasure”—always stop short of sex.

To read The Virgins is to be reminded of the way that, to young people in a certain state of mind, any small threshold in life can be eroticized: diving into a pool, inhaling from a joint, unwrapping a gift. What comes next? Pleasure, sometimes, or a loss of self, or a faltering sadness: “Afterward, the bright wrapping paper lies on the carpet in long, torn strips and crumpled balls. Yards of ribbon, immaculate bows, the hand-cut kind, like huge hydrangeas, that will go straight into the garbage in the morning.” We mythologize sex until it happens and then we long for the pretty innocence it replaces. Dispelling one mystery only remystifies the way we were.

Which was—how exactly? An act of both memory and invention, Bruce’s story unfolds in pieces, in long and short chapters, as if to underscore the brokenness or irrecoverability of that state. But he can sort of remember/recreate shards and glimmers: “For none of us was it really about asses and crotches, sucking cock or licking pussy,” he says. “We beginners experienced sex as psyche more than body, as vulnerability and power, exposure and flight, being consumed, saved, transfigured. To fail at it—to do it wrong—was to experience … the death of one’s ideal soul.”

That headiness can get a little exasperating. Grow up! I found myself crying at the protagonists, which is of course the point. (Not to mention that a bit more cocksucking might add some needed grit to all the gauzy transcendental longing.) But Erens knows how to temper adolescent portentousness, if not through humor, then through warm evocation. Through the lonely Bennett-Jones viewfinder, she captures teenagers’ receptivity to the world, their desire to lose themselves in it. They are panamorous; having not yet learned to focus their ardor, they fall in love with everything. That suggestibility makes her characters delicate and sympathetic; you worry about them as much as you are annoyed by them. But they also seem to possess a special capacity for heightened experience. In one scene Aviva rides a bus to Boston, noticing the engine sending its “vibrations through the vinyl banquette seats and into her thighs. … Her jeans tighten against her crotch and she feels herself contract to a sharp, sparking point. … It is so simple just to tighten gently inside the way she does when she wants to hold back her pee, channeling the shuddering of the moving bus.” Such is the metaphysics of The Virgins, that the potential eroticism in all things makes them all secretly significant.

Plus there’s the matter of who’s telling us about those thighs and that shuddering. At best, Bruce’s preoccupation with the intimate vagaries of Aviva’s body—the license he gives himself to imagine her pleasure—seems inappropriate and creepy. (And even recounting these details, he is seducing her; Aviva is a reader and consumer of narratives.) At worst, it is predatory. “Over the years I’ve come to understand that telling someone’s story … is at one and the same time an act of devotion and an expression of sadism,” he says. “You are the one moving the bodies around, putting words in their mouths, making them do what you need them to do.” Unlucky with flesh-and-blood Aviva, Bruce relishes his control over hallucinatory Aviva, who also tends to appear when he’s masturbating. Even more dangerous is his talent for conjuring up scenes so achingly innocent, so sweet, that you forget their source. “He [Seung] watches her, always. They go on and on, then rest without talking. They daydream for a long time, and then one or the other begins the touching again. The afternoon is endless. No one will come bother them, no one will knock on the door.” It sounds beautiful at first, this figment from a fallen consciousness. But how does he know? How dare he intrude? Spend enough time with Bruce, and the merest brush of sensation turns tawdry and degraded.

Erens’ young characters are often conducting what seem like cosmic tremors, “channeling” forces of pleasure and danger they don’t quite understand. Take Seung, for instance. He is a stoner with a “passion for intoxication.” He’s discovered “that there is something behind or beyond what ordinary experience presents to him, something he privately calls the inside.” He has arranged his life around this revelation: Even his chosen sport, swimming, requires him to surrender his body to a foreign element. For reasons I won’t reveal here, Seung’s search for tactile, spiritual, and sexual immersion, for loss of self, becomes impossibly wrenching. It takes him to a place where Aviva—a girl who can’t resist checking her reflection in windows “to make sure she is sufficiently vivid, not fading away”—cannot follow. Yet Aviva has a side to her personality that encourages Seung’s journey: “There’s something in Aviva that calls out: Drown.” All sirens have that. Bruce, at least, a reader of Greek myths, must have known in advance how the story would end.

Photo by Miriam Berkley

Rather than a space that feels as though it could actually exist, Aviva and Seung inhabit a separate, sealed-off world—a kind of hypersensory Eden, where everything seems extra rich and lush. All surfaces are strokable. You can feel the weight of bodies moving: the “panting” crew team “crammed tight” in the shell; Seung’s finger tracing a word on Aviva’s hip. (And that bus ride!) So much stimulation can be exhausting. And occasionally, serpentlike, a grubbiness or ugliness creeps in.

That ugliness may or may not be Bruce’s fault. “I’ve spent my adult life among people superlatively aware of how the angle of light in a room illuminates their faces,” Bruce, who notably has grown up to be a stage manager, says. “Who know the trick of drawing attention to themselves by withdrawing theirs from everyone else. Aviva had an instinct for these theatrical techniques.” In other words, she is arranging herself to be seen, placing herself at the center of the drama Bruce is spinning. This sounds an awful lot like rape-apologist blather about “asking for it.” Perhaps it should tell us something about the topsy-turvy, sex-crazed inner life of our narrator. When you hold a hammer, everyone looks like they want to be nailed.

---

The Virgins by Pamela Erens. Tin House Books.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.