The Joy of Gay Cooking

Illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker

Gays have been associated with the decorative and the performing arts—fashion, interior design, hair and makeup, dance, opera, and musical theater—almost as long as the identity label has existed. Whether these stereotypes are still valid or meaningful today isn’t what interests me here. Instead, I want to add something to the list, an art form that has been largely overlooked when considering the specific influence of gay men in our culture: I want to talk about gays and the culinary arts.

To be clear, I am not in the least interested in defining such a thing as gay food—not that many people haven’t tried, usually in less than sympathetic terms. But as a gay man who has been cooking professionally for more than 20 years, I have observed in myself and others what I call a gay approach to cooking, an approach that is rooted in our gay identity. I hadn’t given this much of a thought until fairly recently, when I realized that, even though a large part of America’s food world is, in fact, gay, and the popular obsession with food preparation continues to expand all kinds of notions about the food world, gay cooking has remained firmly in the closet. What follows, then, is an attempt to force a grand coming-out.

My obsession with cooking began long before I knew I was attracted to men. I suppose everyone’s childhood memories involve food in one way or another; in my case, I always wanted to know how it was made. My parents were avid hosts of lavish dinner parties. We were living in Paris then, and it seemed that my mother always served the same classic French menu: an appetizer of baked diver scallops, a roasted leg of lamb with sauce béarnaise, gratin dauphinois and haricots vert, a salad course, assorted French cheeses, and a charlotte russe with crème anglaise for dessert. I remember it so well because I was always in the kitchen with her when she prepared it, eager to help. The morning after, I would get up early to find tasty leftovers on the dining room table and in the kitchen. In those days, the 1970s, adult dinner parties lasted into the wee hours, and by the time everyone left, the hosts were too tired to bother cleaning up before going to bed. Those stealthy morning-after tidbits—sips of stale gin-tonics; cold pieces of lamb in congealed roasting juices; rubbery corners of cheesy gratin; the hardened, tarragon-flavored béarnaise; oozing camembert; and most of all, intoxicating spoons of kirsch-soaked ladyfingers with raspberry jam and vanilla sauce—are forever locked into my brain. I absconded with these morsels not because I was hungry; I just wanted to know how the food I had helped prepare had turned out. I even went as far as to wonder how it could be improved. I was 5 years old and already a prissy snob.

I would spend most of my free time as a child in kitchens—at home, at my grandmothers’, and even at my friends’ houses. Only recently did it occur to me that the draw was not only the cooking itself, but also the fact that it was done by women. Their playful banter, warm energy, and precise-yet-relaxed way of going about the task of preparing family meals was so much more appealing to a sensitive, petite boy like me than the competitive, combative attitude of other boys, who seemed forever engaged in some team sport or war game. And so I began to emulate what these women were doing. I learned fast. By the time I was a teenager, I was throwing little dinner parties for my friends and became notoriously opinionated about anything that related to food. It would be another 10 years before a serendipitous opportunity turned the hobby into a career: But today, I am a successful private chef, working for a growing number of clients in New York City and the Hamptons. My style of food is eclectic, and my approach very different from those shown in most media representations of the food world. I call it the Joy of Gay Cooking.

What distinguishes my approach from the prevailing popular cooking philosophies is this: There are no rules, no repeats, no creative limitations, and no anxieties. There is no competitive spirit, no earnest posturing, and no nitpicking. Just pure, blissful fun, spiced with a healthy pinch of self-mockery and irony. Does it get any gayer than that? Granted, it also calls for diligence, some knowledge, experience, intelligence, fearlessness, a bit of patience, and, of course, curiosity. Come to think of it, it’s very much like the joy of sex—gay or otherwise.

|

The Child, the Bear,

the Queen, and the Artist |

||

|

The Straightening of American Cooking

|

||

|

The Terrible Reign of the Iron Chef

|

||

|

Cozy Lesbians and Colonialist Bros

|

||

|

The Art of Simplisissyty

|

This five-part series will explore how gay men and their particular sensibility have played a major part in America’s culinary awakening, how their legacies have been gradually stripped off their more idiosyncratic and flamboyant elements to suit the increasingly heteronormative and commercial values of the contemporary food scene, and why it would be to everyone‘s benefit to reintroduce resolutely gay voices into the national dialogue on the culinary arts. In fact, if it weren’t for the initiative of three highly distinct gay men, the breathtaking leap America has made in the past 50 years that transformed the country from a culinary backwater into the world’s leading food nation might never have happened.

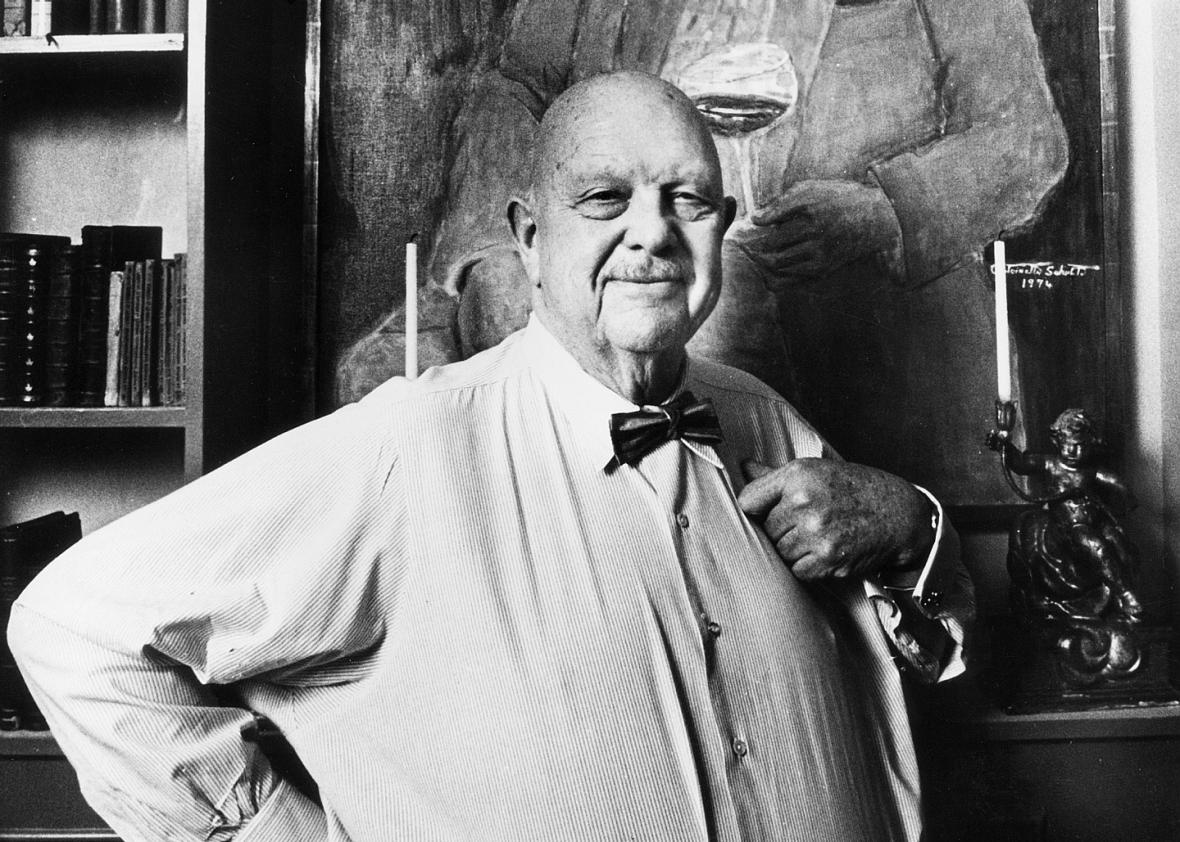

A little known (or at least underappreciated) fact: James Beard, the late, legendary dean of American cookery and namesake of the prestigious James Beard awards, was gay—uncompromisingly and openly gay. A larger-than-life epicure from Oregon who harbored dreams of becoming an opera singer (or at least a musical theater performer), Beard was the first man who showed Americans that food can be a pleasure, that it can be done at home, and that you can either do it yourself or pay someone else to do it for you. It was a crucial cultural shift. By the 1960s, 20 years after the start of Beard’s juggernautical career, the puritan country began to gradually understand that the same principles could be applied to sex—another thing that America’s gay men, typically ahead of the curve, had known for decades.

Photo by Dan Wynn. Courtesy of James Beard Foundation.

A performer at heart, Beard became the host of television’s first ever cooking show when Julia Child was still a student of French cuisine at the Cordon Bleu school in Paris. He wrote a recipe book about hors d’oeuvres 50 years before Martha Stewart, advocated cooking with seasonal and local ingredients decades before Alice Waters opened Chez Panisse, and studied 19th-century American cookery at a time when everyone was still obsessed with French cuisine. He was, by all accounts, an imposing father figure with an insatiable hunger for food, sex, and money; famous for his big temper and even bigger heart; and constantly on a mission to get as much pleasure out of life as possible while inspiring people to cook great, straightforward, preferably American food. Fondly remembered by all those whose lives he touched in his enormous outreach, he was rewarded with immortality when his friends posthumously created the now world-famous James Beard Foundation in his townhouse in the West Village.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The second leading gay figure in the pantheon of America’s culinary world was Craig Claiborne, a man who single-handedly made restaurant reviews a legitimate form of criticism in America during his long reign as the all-powerful food editor of the New York Times. A shy lad from the South, he had smartly used his G.I. Bill benefits to follow his passion for food and study at one of Europe’s premier hotel schools in Switzerland, where he became obsessed with French haute cuisine and the decorum of fine dining. If James Beard had opened the door to make food an interesting and viable subject in America, Claiborne would become the country’s arbiter of good taste, the Truman Capote of food writing who introduced the American palate to worldly sophistication. Exploiting the Times’ considerable clout and expense account with the insouciance of an established Hollywood diva, he bridged the previously separate worlds of restaurant dining and home cooking by writing extensively about restaurant chefs as well as accomplished home cooks. Claiborne was also no stranger to controversy and scandal: In 1975, he rewarded a $4,000 meal (about $20,000 today) at a fancy Parisian restaurant with an unfavorable review, causing a public uproar so intense that even Pope Paul VI felt compelled to publicly denounce his decadence—quite a badge of honor for a gay food writer.

Courtesy of Bricktower Press.

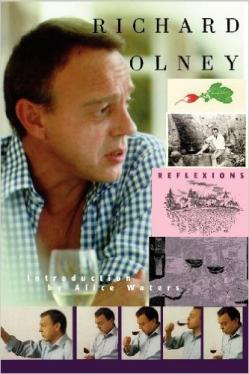

The third player in this holy gay trinity of the culinary world was Richard Olney, a bohemian expat artist and food writer who, though he lived the life of a hermit in Provence, practically invented the then-revolutionary notion that home-cooking could be highly exacting and uncompromising in its traditional technique, yet resolutely modern and casual in its presentation. Often a contrarian figure in the established food publishing world, he never relented in his philosophical, noncommercial, and sensuous approach to food, becoming a godfather of purist chefs in America and Europe. A mentor (and one-time lover) of one of America’s most revered restaurant chefs of the next generation, Jeremiah Tower, he was also the editor of Time Life’s monumentally influential series The Good Cook, the first cookbooks that used minimalist step-by-step photographs to explain traditional cooking technique. I, for one, studied them religiously when I was a teenager.

It’s no coincidence that each of these three men—men who, together with their three female counterparts Julia Child, M.F.K. Fisher, and Alice Waters (and editor Judith Jones, acting behind the scene as the godmother of food writing), paved the way to America’s culinary coming-of-age—was gay. I have no doubt that their obsession with the preparation of food was deeply connected to their gay identity and that their lifelong dedication to it helped them live out related aspects of their respective personalities—the bon vivant bear with a penchant for high drama, the aspiring Southern queen with deeply rooted insecurities, and the radical outsider with a poetic streak.

None of these highly complex men were restaurant chefs, which had been for the longest time the only viable male occupation in the food world—until they changed it forever. Each of them did what gay men do intrinsically: They broke the rules to create interesting lives for themselves in the new field of food writing that, at least in America, had been the domain of women. They did not cook for a living—they lived to cook. What’s more, they lived to please themselves, to celebrate the bounty of nature—and to share it. Their impact on America’s culinary culture was exciting and palpable, but their spiritual legacy would soon be overshadowed by new trends that gradually transformed the joyful kitchens they had carefully built into a circus that treated cooking not as an action, but as an act.

Next course: When did American cooking get so straight?