Videos Are Better Than Photographs

The rise of short-form video services is going to make the snapshot obsolete.

Photo by Mike Windle/Getty Images for Huggies

For the past few months, I’ve been noodling with the blasphemous idea that photographs are kind of silly and maybe even outdated. I don’t mean professional or artistic pictures. I mean amateur ones: snapshots, pictures of your kids, pets, vacations, Thanksgiving at Grandma’s. A decade ago, cellphone cameras and social networks gave new life to the family photograph. We could take dozens of pictures of everything around us and share them with everyone. This sounds kind of nightmarish, but it turned out to be a boon for both photos and the Web. Facebook is as big as it is thanks to snapshots, and snapshots are as big as they are thanks to Facebook.

But the same technology that reinvigorated pictures is threatening to outclass them. Now that our phones can do video, and our networks are fast enough to transmit and display video, why take snapshots anymore?

In the nearly three years that I’ve had kids—they just showed up on my doorstep one day—I’ve taken thousands and thousands of photographs of them. (According to Picasa’s face-recognition algorithm, I have 3,500 pictures of my nearly 3-year-old son, which is an average of three a day.) I love these photos dearly. Yet when I go through the huge stash, I often find myself skipping past the photos to look at one of the few hundred videos instead.

It’s not just that videos contain more stuff: movement, dialogue, facial expressions, and consequently, more emotional resonance. The more important thing is that videos are truer. As Jenna Wortham wrote recently in the New York Times, “Instagram isn’t about reality—it’s about a well-crafted fantasy, a highlights reel of your life that shows off versions of yourself that you want to remember and put on display in a glass case for other people to admire and browse through.” Wortham likes this about Instagram’s pictures, and she worries that Instagram’s new video feature ruins the fantasy. And I agree that sometimes creating a fantasy of your life can be nice—and a nice way to make other people feel bad about themselves.

Most of the time, though, I don’t want fantasy. I want authenticity. When I’m trying to capture my kid’s birthday party, I don’t want the best moments. I want the truest moments—I want to remember exactly what it felt like, what it sounded like, how frustrated and stressed-out and over-the-moon I was all at once. And for authenticity—or, better authenticity—videos handily beat photos.

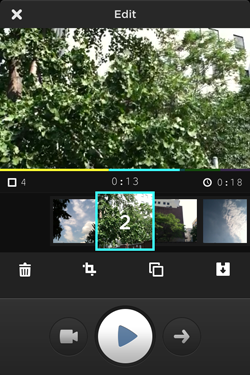

Courtesy of MixBit

Until recently, the only problem with video was that it was too hard to do it well—or, rather, it was too easy to do it terribly. Taking a good photo was easier than taking a good video, so when you wanted to act fast, it was easier to snap. But that’s changed. The rise of short-form video services like Vine, Instagram Video, and now MixBit—the last of these founded by Chad Hurley and Steve Chen, who started YouTube—has given video an edge over photos.

Each of these apps works slightly differently, but they all have the same effect. They all make it easier to capture better videos than you could in the past. First, they all use an interface that requires you to hold down a button while you’re shooting; because you don’t click once to start shooting and click again to stop, you stay focused while you’re capturing video, which results in better clips. Instagram and Vine also limit the length of your videos. (Vine’s videos are six seconds; Instagram’s are 15 seconds.) This prevents your videos from droning on. (MixBit is trickier—each cut is limited to 16 seconds, but you can string together multiple cuts to create videos that are as long as an hour.) These improvements sound slight, but I suspect they will prove deadly to photos. Now that it’s easy to shoot videos that aren’t crap, it usually makes sense to go for clips instead of snapshots. Most of the time, videos are just better.

Yeah, I know this sounds arrogant and overly general. Who am I to proclaim the death of one form of expression in favor of another? And why should they even have to battle it out—can’t they both take off? After all, some situations are better suited to photos and others better captured in motion, and you can always just shoot both.

Yeah, all that’s true. But look at this Instagram Video that Kobe Bryant posted earlier this week:

The video is boring, but if you know the backstory, the clip packs a wallop. In April, Bryant tore his Achilles tendon, an injury that had been projected to take six to nine months of recovery. With this video, in just a few seconds, he can convey to his fans that he’s getting much better much faster than they might have hoped. Bryant could have posted this as a picture, but a picture would have given the wrong impression. Looking through Bryant’s feed, you see that most of his pictures suggest a rich baller’s fantasy life—here he is visiting the Philippines, here he is practicing Chinese calligraphy, etc. The video isn’t color-filtered, and it isn’t artistically edited. It’s not pretty. But it is accessible. It tells a story that feels real.

The Bryant video reminded me of something Kevin Systrom, one of Instagram’s co-founders, told me during an interview last week. “The things that end up being important for video are the moments where it's not really the aesthetic of the moment that matters as much as it is the moment itself,” Systrom said. He pointed out that people often use Instagram as a way to communicate with their friends. “The reason you take a picture of your latte is not because you think your latte looks really good, even though there are lots of beautiful lattes out there. But there are lots of unbeautiful lattes, too. I think the reason people take photos is a way to send a message saying, Here's what I'm doing, here's who I'm with. Instagram allows you to do that, and I think people can do that really effectively with videos. It's a status update in a visual form.”

Courtesy of Vine

You might argue that people don’t want to be authentic in their updates—that we want to present a fantasy rather than reality, and that this desire accounts for Instagram’s popularity. But I think that oversells the case. When I pull out my camera, I’m aiming to record the moment for myself as well as for other people. I want to show off, but I want to create a document that lets me remember what was happening, too. I think that video allows for more nuance in the trade-off between presenting fantasy and capturing reality. With a 15-second video you can show off more of your vacation than just the cliché of a beautiful sunset. You can show off the fantasy of eating at the French Laundry and the horror of being presented with the bill, the joy of taking a Venetian gondola ride followed by the horror of being stuck in a plane with a toddler.

There’s one more reason I think videos are bound to eclipse photos. Technically, there’s a lot more room for improving amateur videos than there is for improving amateur snapshots. Today—thanks to Instagram-like filters, autofocus, and super fast, super high-res cameras—the best amateur photos can be as good as the best professional ones. Our photos are as good as they’re going to get. But that’s not true of videos. Professional videographers have access to much more expensive and sophisticated tools than the rest of us. “There are things that Hollywood has been doing for quite some time that aren’t intuitive to users,” says Hurley of MixBit. “I think we have ways to lightly introduce those concepts in our apps.” And once those tools become more widely available, they’ll produce stunning results that will push a lot more of us to choose clips instead of pics.

Let me end with one such example. Last Friday, a woman named Alexandria Stack was driving along Interstate 96 in Michigan. She had her smartphone out. She captured this Vine, something that would have been impossible with a photo:

The driver is expected to make a full recovery.