When I signed up for an Instagram account last week, my colleagues told me what to expect. “Your feed will be 50 percent pictures of food, 25 percent selfies, and 25 percent sunsets,” they said. (There were variations: “Twenty-five percent pictures of food, 25 percent urban flotsam, 25 percent people hanging out, and 25 percent sunsets,” predicted one editor. Or “20 percent selfies, 60 percent dogs, and 20 percent sunsets.”) Amid the shifting ratios of glamour shots to guacamole to Great Danes, sunsets were a constant.

After my first few times logging onto Instagram, I could see why. The sun setting over Manhattan. The sun setting over the ocean. The sun setting over a lake. The sun setting over a field. The sun setting over a mountain. The sun setting over trees. I got used to the crepuscular shades shimmering in my photo feed every time I clicked. A Martian anthropologist peering over my shoulder would probably conclude that our civilization saw something unutterably holy in day’s passage into night (though I don’t know what he’d make of all the omelets and Bundt cakes). If Facebook is where we plaster wedding and baby pictures, and Twitter is where share links and quips, think of Instagram as the last refuge of that much-maligned photographic cliché: the sunset shot.

Maybe we shouldn’t be surprised. The colors of dusk and daybreak have entranced us since Homer first warbled about rosy-fingered dawn almost 3,000 years ago. In folk tales, sunsets are times of metamorphosis and possibility. The Jewish day begins and ends with them. Claude Monet, John Constable, and J.M.W. Turner painted them over and over. As Paul Fussell writes in The Great War and Modern Memory, the chroniclers of World War I were especially drawn to sunsets, in part because they broke up the monotony of the trenches, resembled a more beautiful version of artillery fire, and captured something about life’s evanescence.

But the sunset has always been a troubled subject for photographers. One co-worker recalled taking a beginning photography class in which rule No. 1 was no sunset pictures. (“Wow! Another sunset! Who’d have thought?” she remembers the teacher scoffing on the first day, examining the cirrus-heavy clips her students had brought in.) Although the impulse to snap a sunset is understandable—it is probably the loveliest thing one sees all day (unless one wants to wake up at 5 a.m. for the sunrise)—the resulting photographs often disappoint.

The genre has turned into a commonplace—a grab at easy beauty. My friend, an amateur photographer, likened shooting sunset pictures to “eating Lucky Charms for breakfast.” “What do you mean,” I pressed, speaking as someone who faults Lucky Charms only insofar as they aren’t Fruit Loops. She elaborated: “They’re sweet and anodyne. The effect is like a sugar rush that disappears.” Buried in her objection is the hoary philosophical distinction between the beautiful and the sublime, between prettiness that doesn’t challenge us and sights that fill us with awe and terror.

Romantic writers expressed a preference for sublimity over attractiveness in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Edmund Burke wrote, “For sublime objects are vast in their dimensions, beautiful ones comparatively small: beauty should be smooth and polished; the great, rugged and negligent … beauty should not be obscure; the great ought to be dark and gloomy: beauty should be light and delicate; the great ought to be solid, and even massive.” The experience of watching a sunset usually counts as sublime. The scene unfolds on a grand scale, loud with color and radiance; you get a shivery feeling of time passing as you sip your G&T; death draws just a bit nearer. Sunset pictures, though, reduce and tame that sublimity. Instead of your mortality rising to meet you, you see pretty colors, locked in a small and tidy moment. It’s as if putting sunsets on film magically relegates them to the same cloying aesthetic category as wildflowers and blonde children—other people’s.

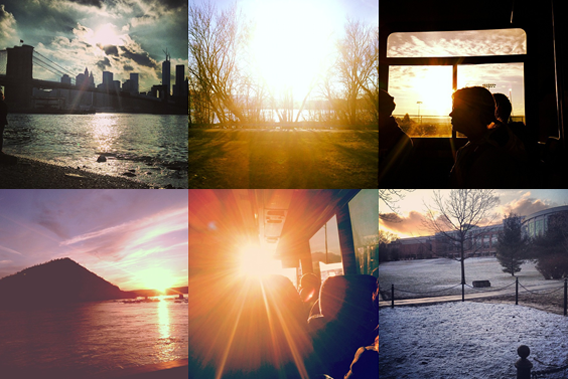

Yet, even though capturing a sunset in all its glory is a difficult proposition, people will try, and sometimes they score some pretty nice shots. Scroll through any Instagram feed: Some photos have a restful, pensive mood; others makes you sad; others would set Burke trembling with their apocalyptic fury. A single orb floating in the center of the frame can evoke the artist’s lonely consciousness (sunset pics: Just another type of selfie!), or it can remind you of the terrestrial vantage point we all share. Perhaps the real problem with the sunset shot is that it can be tricky to pull off. That’s where the experts come in.

“I have nothing against sunsets,” says Robert Caplin, a professional photographer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, National Geographic, the Wall Street Journal, Time, and elsewhere. Caplin is also an avid Instagrammer. “Photography means recording beautiful light. And sunsets are all about beautiful, colorful light.”

For him, the challenge of the sunset Instagram inheres in learning to maximize that light. (A self-professed “Instagram purist,” who sees the site as creating “a diary of your life through your iPhone,” he rejects the idea of Instagramming shots taken from a stand-alone camera.) Many would-be photographers simply point their devices in the direction of the sunset and press the shutter button, he says. The cellphone automatically exposes for the darker regions of the shot—the shadowed area below the horizon—and floods the entire frame with illumination, washing out the subtle colors of the sky. Caplin recommends avoiding over-exposure by tapping the brightest part of the picture before you shoot. This will adjust the amount of light falling on your phone’s image sensor so that the area below the horizon remains dark, while the colors in the sky pop out. “You’ll get that saturated, contrast-y, exposed look, which is key,” he explains. (For those with fat fingers, or those in search of a more virtuosic alternative, Caplin suggests pointing your camera phone at the heavens; then quickly framing and snapping your shot before the phone can recalibrate for shadows. Sneaky!)

But tackling exposure is just the beginning. “To take your sunset to the next level, throw in other details,” says Caplin. “Add silhouettes of people; background elements like statues, lampposts, buildings.” In his twilight photos, he says, he likes to “give the viewer more information about where I am and my surroundings,” because “different lines make your eye wander around.” Slate photo editor Juliana Jimenez echoes Caplin’s praise for secondary elements. “Add in a silhouetted city skyline in the background, a reflection off a window, the round organic shapes of sunglare in contrast with rectilinear sunray spires, and the combinations and possibilities for beauty are endless,” she writes.

(As for filters, “Sure, I use them,” Caplin says. “But even better is the contrast button, which can really bring out the brightness of the clouds against the sky.”)

And then? Post away. Or go for the homerun: you, your pet, and a homemade berry crisp, all under a quaintly bent street sign, with the sun sinking like a jewel in the background. Sunsets may be like snowflakes—no two are alike—but at least they afford you plenty of opportunities for practice (365 a year!). And anything’s better than baby pictures.