Bug-Out Scenarios

How do climate scientists cope with existential dread?

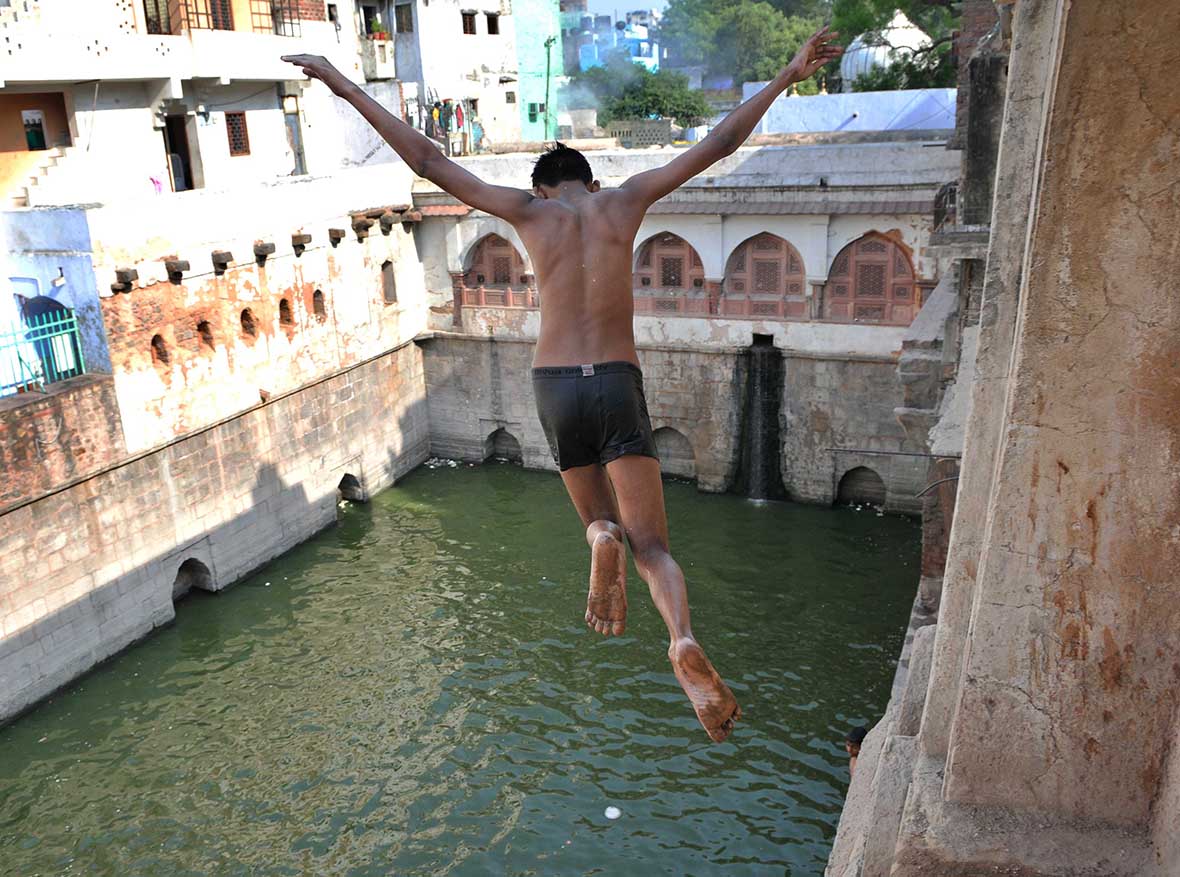

Photo by Herman Verwey/Foto24/ Gallo Images/Getty Images

There’s been a rush of dystopic news on climate change in the past week or so. An off-the-charts burst of west winds in the Pacific Ocean is locking in one of the strongest El Niños on record, virtually guaranteeing that 2015 will be the hottest year in human history. The weather system has spawned a rare triplet of China-bound typhoons. All-time temperature records were set in Spain, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany in a crushing heat wave. Widespread wildfire in Alaska is burning through permafrost, and lingering smoke from huge Canadian fires gave Minneapolis its worst air quality in a decade. In the Pacific Northwest, under intensifying drought, even the rain forest is on fire.

If this is what climate change looks like already, the future is pretty much screwed, right? Well, maybe. Despite a few memorable moments of intense realism on the global stage, world leaders have essentially done nothing. Existential dread is fairly common among those who work on climate change on a daily basis.

That’s the theme Esquire’s John H. Richardson explored this week in a fascinating and frank discussion with Jason Box and other climate scientists. I’ve had my own run-ins with climate change despair, and this article strikes me as a fascinating insight into the psychology of an increasingly apocalyptic science. You should read the whole thing, but here are some highlights. Richardson describes Box as “oddly detached from the things he’s saying, laying out one horrible prediction after another without emotion, as if he were an anthropologist regarding the life cycle of a distant civilization.”

But that doesn’t mean Box is unfeeling. In a photo caption, Richardson reveals the money quote highlighting Box’s ever-present malaise: “The customary scientific role is to deal dispassionately with data, but Box says that ‘the shit that’s going down is testing my ability to block it.’ ”

In the face of all this, Box and his family relocated from the United States to Denmark. Richardson explains their decision:

His daughter is three and a half, and Denmark is a great place to be in an uncertain world—there’s plenty of water, a high-tech agriculture system, increasing adoption of wind power, and plenty of geographic distance from the coming upheavals. “Especially when you consider the beginning of the flood of desperate people from conflict and drought,” he says, returning to his obsession with how profoundly changed our civilization will be.

In fact, Box often thinks about the profound planetary changes that are already underway:

His home state of Colorado isn’t doing so great, either. “The forests are dying, and they will not return. The trees won’t return to a warming climate. We’re going to see megafires even more, that’ll be the new one—megafires until those forests are cleared.”

But the real success of the Richardson piece is the way he depicts the internal struggle Box deals with on a daily basis.

“But I—I—I’m not letting it get to me. If I spend my energy on despair, I won’t be thinking about opportunities to minimize the problem.”

His insistence on this point is very unconvincing, especially given the solemnity that shrouds him like a dark coat. But the most interesting part is the insistence itself—the desperate need not to be disturbed by something so disturbing.

In a moment of candor I hadn’t seen before, Box revealed to Richardson that he’s already preparing for the worst:

“In Denmark,” Box says, “we have the resilience, so I’m not that worried about my daughter’s livelihood going forward. But that doesn’t stop me from strategizing about how to safeguard her future—I’ve been looking at property in Greenland. As a possible bug-out scenario.”

Despite what the Esquire article says, Box, whose work I have previously covered on Slate, is a bit of an outlier among climate scientists. Most of them aren’t as willing to talk about the plausibility of nightmare scenarios. Still, his frankness on climate change is welcome.

Ultimately, what scientists are after is truth, even if that truth is personally devastating. For that reason, being a climate scientist is probably one of the most psychologically challenging jobs of the 21st century. As the Esquire article asks: How do you keep going when the end of human civilization is your day job?

I reached out to a few well-known climate scientists for their reactions to the article.

Michael Mann, a Pennsylvania State University meteorologist whom Richardson quotes, told me, “I would emphasize that it isn’t too late to act, despite the sense one might get from the article. Our only obstacle at present is willpower.” When asked about how many climate scientists struggle with psychological dread over their studies, Mann said, “I honestly don’t know how many of my colleagues reflect on the matter. But those who don’t ought to. What we’re studying and learning is more than just science. It has ramifications for the future of humanity and this planet.”

By far the most engaging response was from Katharine Hayhoe, a rising star in the climate science community after her work engaging evangelical Christians on the issue was profiled in a Showtime documentary last year. Time named her one of the 100 most influential people on the planet for 2014.

Hayhoe now lives in Texas, precisely because of its climate vulnerability. Hayhoe said Texas’ “strident political opposition to the reality” makes it “ground zero for climate change,” which her work embraces. “If I personally can make a difference, I feel like Texas is where I can do it.” But she’s quick to applaud Box’s work and doesn’t criticize his family’s decision to relocate.

In the back of her mind, Hayhoe said she has also factored in humanity’s lack of progress on climate change in her family’s future plans. Like Box and his family, Hayhoe also has a bug-out scenario: “If we continue on our current pathway, Canada will be home for us, long-term. But the majority of people in the world don’t have an exit strategy. … So that’s who I’m here trying to help.”