Pacific Rim

Monster-walloping made fun again.

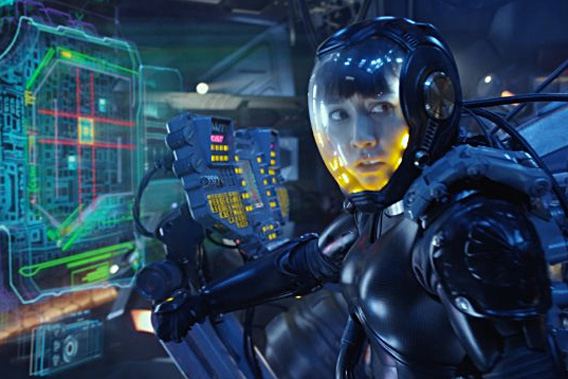

Courtesy of Warner Bros.

After you’ve seen Pacific Rim, come back and listen to our Spoiler Special:

I’m not sure how to justify my sense that Guillermo Del Toro’s Pacific Rim is a cut above your average summer blockbuster in which monsters and giant robots cause major damage to iconic city skylines against a post-apocalyptic landscape. This 132-minute movie certainly has its share of long, hard-to-follow battle sequences, thinly developed human characters, and grating comic relief. Yet somehow coming out of Pacific Rim I felt energized rather than enervated, excited to describe certain nifty details of the film’s wacked-out imaginary world to friends, maybe even ready to … sit through certain parts again?

Pacific Rim is unashamedly a film for little kids—at times it feels almost like a very well-made “look at my toys” YouTube video by a little kid, albeit one with a staggering collection of action figures. But where the Transformers franchise has the soul-deadening effect of an extended toy infomercial, Pacific Rim offers at least some sense of watching an imagination at play. It’s based on an original story by Del Toro’s co-screenwriter Travis Beacham—original not just in the sense that it isn’t based on any pre-existing movie, comic book, TV show, or line of toys, but in the sense that it’s sort of weird. In this movie’s near future, the Earth has been attacked by creatures known as the Kaiju (the word in Japanese means “strange beast,” and is also the name of the genre of giant-monster movies launched by 1954’s Godzilla). The Kaiju—whose rapid evolution means that they can easily appear either as serpentine sea monsters, dinosaur-like land reptiles, or insectoid flying horrors—came from deep within the Earth’s core, but also somehow through a portal to another universe located in an underwater passage called “the Breach.” Humanity’s only defense against these invaders (other than a short-lived experiment at a peaceable “Wall of Life,” which the monsters tear through like so much cookie dough) are gigantic fighting robots called Jaegers (German for “hunters”). Because of their enormous size—we’re talking 25-plus stories high—Jaegers can only be operated by pairs of specially trained pilots, each in command of one-half the robot’s body, their brains locked into a state of intimate connectedness known as “neural drift.”

All this terminology is swiftly laid out in a kind of pre-credits tutorial, in which we also learn that the voiceover provider (and nominal, if cypher-like, main character) is Raleigh Becket (Charlie Hunnam), a once-cocky Jaeger pilot who’s lost his beloved brother and co-pilot to the monsters as a result of disobeying a direct order. That’s not a wise thing to do when your commander is a legendary ex-Jaeger pilot with the glorious name of Stacker Pentecost (Idris Elba). Crushed by his brother’s death, Becket leaves piloting behind and takes a job at the ill-fated Wall of Life, but he’s coaxed back into the cockpit—or rather, the enormous robot torso—by Pentecost, whose embattled Jaeger fleet is making a last stand before it’s phased out by the UN (which in a decade or two will apparently unilaterally arbitrate all worldwide disputes—congrats in advance to whoever turns that organization around!).

To achieve the state of “neural drift” with a co-pilot requires not only a familial sense of closeness—the teams we meet include an Australian father and son, a Russian brother and sister, and a set of Chinese triplets—but an ability to share memories and sense impressions. These inward journeys are also witnessed by the audience, in the form of trippy neural-pathway-cam montages that sometimes morph into legitimate flashbacks. I loved Del Toro’s confident shifts in between psychedelic, vaguely touchy-feely Matrix territory (“Don’t chase the rabbit! Stay in the drift. The drift is silence.”) and introspection-free monster-on-robot action, though I might have wished for a little more world-building in place of the world-destruction. The sheer scale and design of the creatures remains thrilling even when, for those not versed in the kaiju and mecha cultures that inspired the beast and ’bot designers, their sessions of whaling on each other get a little confusing and redundant. At least Del Toro mixes up the look and staging of the fight scenes—one in midair, the next (spectacularly) underwater, the next a semicomic encounter with a hungry baby Kaiju just burst from the womb—so that we never know what to expect next from these rapidly mutating world-marauders.

The human stories that take place in the interstices between Kaiju/Jaeger battles and neural-drift freak-outs are the Achilles’ heel in Pacific Rim’s ingeniously designed armor. Idris Elba is effortlessly charismatic (not to mention knee-meltingly handsome) as the authoritative Pentecost, and he gets off one good laugh line when a subordinate dares to invade his well-policed personal space. But Pentecost’s longstanding paternal relationship with the young female pilot Mako Mori (Babel’s Rinko Kikuchi) is sketched far too hastily to resonate with the audience, as is Mori’s partnership-turned-romance with Hunnam’s Becket. Becket has to be one of the most unprepossessing male leads in an action movie since Ryan Reynolds in The Green Lantern. Not that it’s entirely Hunnam’s fault, given that his character description can be reduced to “blandly attractive guy who’s sad because his brother died.” I didn’t mind Pacific Rim’s sometimes hokey dialogue, like the once-more-unto-the-breach oration in which Pentecost inspires his Jaeger team with the promise that “Today, we are canceling the Apocalypse”—it all seemed like part of the movie’s genial Saturday-afternoon-matinee vibe. But I wish those cheesy lines had been spoken by characters I’d had at least one more scene to get to know.

Opinions will be divided on the comic-relief segments featuring Charlie Day and Burn Gorman as two bumbling scientists with conflicting theories as to how to approach the study of Kaiju. Day’s character, whose obsession with procuring an intact Kaiju brain eventually gets him mixed up with black-market organ dealer Hannibal Chau (Ron Perlman), has a high-pitched voice and manic demeanor that frayed at my nerves, but I suspect the character’s broad humor and insatiable curiosity will appeal to young viewers—it’s a role Rick Moranis could have played back in the day. (Come back to the movies soon, Rick.) Perlman, a constant in Del Toro’s filmography long before his stint in the Hellboy movies, gets little to do with his enormous screen presence other than snarl at underlings while wearing steampunk goggles and gold-plated shoes (I wanted an extended Perlman-led tour of the Kaiju-organ-harvesting underworld, with all the rad props that would no doubt entail). Perlman does appear in a goofy mid-credits stinger that, refreshingly, drops nary a portentous hint at a sequel. But Pacific Rim’s ability to make monster-walloping feel fun again will no doubt make Atlantic Seaboard (or maybe Mediterranean Coastal Region) as inevitable a follow-up as the return of the Kaiju through that pesky underwater portal.