Lame-Duck Soup

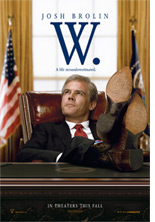

Oliver Stone's cinematic portrait of George W. Bush.

Oliver Stone's W. (Lionsgate) sounds on paper like the worst idea of the director's career, if only because of the timing of the movie's release. The George W. Bush of late 2008 isn't just a lame duck, he's a really lame lame duck. Present in the campaign only as a negative example for both parties, the president has nearly disappeared as an object of popular opprobrium or late-night satire. Our disgust with him is so omnipresent that it's gotten tedious. As late as 2007, it was still possible to marvel at Bush's bottomless gift for malapropism and mediocrity. These days, when you come across a recent statement by the president, your first response is more like, "He's still talking?"

To listen to Slate's Spoiler Special about W, click the arrow button on the player:

The nation's advanced stage of Bush fatigue would seem to make the 43rd president a poor target for Stone's ever-present tone of fevered moral outrage. But what's surprising about W. is the tone that it does manage to strike, which is both lighter-hearted and fairer-minded than you might expect. Neither satire nor biopic, the film is a kind of secular pageant, enacting with dogged literality the well-known stations of the cross of Bush's life: the 40th-birthday hangover-turned-religious-conversion! The near-asphyxiation by pretzel! Mission accomplished! "Is our children learning?" The moments scroll up the screen like the song titles on one of those greatest-hits collections advertised on TV. The movie is done in the broad strokes and primary colors that are Stone's trademark—lest you've forgotten JFK, this is not a filmmaker of nuance—but the net effect is both satisfying and strangely cathartic to watch.

W. is at heart the story of Bush's Oedipal struggle, his lifelong resentment of and identification with his WASPy, upstanding, unsatisfiable father (beautifully played by James Cromwell). Indeed, the movie reads Bush the younger's entire political career as an attempt to avenge Bush père's loss to Clinton in 1992—a psychodramatic interpretation that, according to some sources, is not that far off base. Beginning with an early scene in which the college-age W (Josh Brolin) calls his father from jail in a bloodstained Yale sweatshirt, the movie's chief conflict is not between Bush and his advisers or even Bush and himself (the story of W's internal struggles would be more of a one-reeler) but between this charming, energetic, directionless man and his remote paternal ideal.

There's little that's news at this point in the George Bush bio, so I'll leave the movie to surprise you where it can. Its hectic temporal structure, which crosscuts between Bush's pre-presidential days and the run-up to the Iraq war, is generally legible, though a framing device in which Bush imagines himself alone in the Texas Rangers baseball stadium is predictable and overly symbolic. Many of the performances are fascinating in a wax-museum way, simply by virtue of the actors' resemblance to their Bushworld prototypes. (Rob Corddry as Ari Fleischer is one such visual joke, too quickly thrown away.) Thandie Newton nails Condoleezza Rice's nasal drone and stiff posture with frightening perfection, but her role as written never rises above the level of political caricature (though she does milk a big laugh from her memorably dry delivery of the single word amen).

But a few of the actors, particularly the superb Brolin, go beyond impersonation to plumb the depths of some notoriously unplumbable public figures. Richard Dreyfuss can scarcely conceal his delight at getting to play Dick Cheney, the administration's great mythic villain; he literally lurks in doorways during Cabinet meetings, shoulders hunched and jaw askew, muttering apocalyptic pronouncements straight out of Dr. Strangelove. Dreyfuss' interpretation would seem over-the-top were it not for the fact that (as Timothy Noah documents here), Cheney apparently did lurk around saying stuff like this. All I know is, whenever Dreyfuss sidled on-screen, I was awash with glee. Watching these well-known actors get trotted out one by one in the Halloween costumes of the Bush Cabinet becomes a kind of parlor game: Whom would you cast as Colin Powell? Why, Jeffrey Wright, of course! (Wright, as always, is fantastic, almost too good for the part he's in; he could be starring in a separate, tragic film about a hero's self-betrayal.)

My enjoyment of this film hovered perilously close to camp at times. Stone's musical choices lay it on particularly thick: He accompanies a party scene during Bush's drinking years with the Freddy Fender song "Wasted Days and Wasted Nights" and scores the fall of Baghdad to the marchlike rhythm of "The Yellow Rose of Texas." But if Stone's portrait of George Bush is laid on with a trowel, maybe it's because God seems to have engineered the real Bush's life with a similarly crude sense of irony. W. is a case of biographer and subject being perfectly matched: You really don't want a Bush biopic directed by Jean-Luc Godard (though Robert Altman could have done something interesting with it if he were still around). Like Tina Fey's Sarah Palin, Stone's George Bush gets his best lines straight from the source. This movie was scripted by screenwriter Stanley Weiser (Wall Street) but was ghostwritten by history itself.