Where Is Jay Gatsby’s Mansion?

And can I visit it?

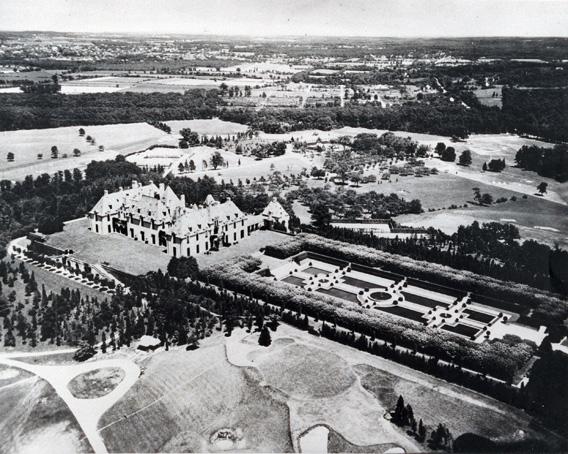

Photo courtesy of Oheka Castle

Citizen Kane’s Xanadu fell into disrepair before it was ever finished. Hogwarts is now a tourist trap in Florida. Even Eloise’s quarters at the Plaza Hotel have recently been relocated to Brooklyn. Of all the fictionalized places to live, there are few that have remained dignified in their power of fantasy for as long as Jay Gatsby’s mansion. Its opulence, raucous throw-downs, and deep metaphors have rendered it one of the sexiest houses ever conjured and the everlasting cathedral of the Jazz Age. Right down to Gatsby’s then-state-of-the-art juicer, Fitzgerald spared no corner from lavishness, and to the scrupulous who may think it all too over the top to ever have existed, guess what—it did. But existed in what sense? What was Fitzgerald’s muse for such a palace? If there is a real Gatsby mansion, where? Take me, let’s go.

Let’s also go ahead and dispel another common perception: Gatsby’s house was not ostentatious. Judgment is in the eye of the beholder, and the eyes that would have beheld Gatsby’s mansion would have belonged to the nation’s most elite subset, whose homes were equally elaborate, if not more so. Between the Civil War and World War II, an estimated 975 estates were built between Manhattan and Montauk, though this number wavers depending on the historian. Approximately one-half remain, so no one can be sure. The stretch of land was a new frontier: undeveloped farmland begging to be converted into polo fields, golf courses, country clubs and gardens—an idyllic playground in which the wealthy could recess when they weren’t holed up in skyscrapers and amassing millions.

The most desirable portion of this stretch was the North Shore, the northern coast of Long Island that borders Long Island Sound, which was nicknamed the Gold Coast (for obvious reasons) and was the de facto location of Fitzgerald’s East and West Eggs. Fitzgerald approximates Gatsby’s property at 40 acres; many estates in the area were hundreds of acres. Gatsby’s mansion was modeled after a Hôtel de Ville in Normandy; some estates literally were châteaux, taken apart on one side of the Atlantic and pieced back together on the other. Play the name game with any of America’s great families—Vanderbilt, Astor, Guggenheim—and chances are they had a Gold Coast residency and perhaps still do.

Back to the Eggs, lest they get scrambled. East and West Egg are Cow Neck and Great Neck, respectively, two peninsulas of Nassau County that border Manhasset Bay. Cruising through this body of water is a lesson in all of the things you should and shouldn’t do, should you ever design a dwelling the size of the White House. They line the water one after another—more shoulds to the east, shouldn’ts to the west—until, like open gates, the land on either side culminates in final, identical tips, marking the end of the bay and the beginning of the Sound. The point to the right is Sands Point East Egg—a village at the end of Cow Neck. This is where Fitzgerald placed Daisy Buchanan's residence with the infamous green light.* To the left: Great Neck—West Egg—Kings Point. Gatsby.

Fitzgerald describes the points as being similar enough to confuse the gulls flying above. At water level, too, they look the same, with each plot of land cascading gently downward into stockpiles of rocks. The difference is at a societal level. Great Neck has a greater number of ethnicities and newly built homes. Manhasset is only slightly wealthier, but it is much more traditional in the privatized way that often accompanies circles with longstanding histories and inheritances; according to the 2010 census, nearly half of its homes were built before 1939. Both are home to the 1 percent, but Manhasset has been so longer.

Fitzgerald moved to Great Neck with his wife, Zelda, in the fall of 1922. Although the “less fashionable” of the two municipalities, it still abounded in the societal glitter he had long craved, not unlike the young Jay Gatsby. Fitzgerald wrote by day and partied alongside Hollywood heroes, Broadway stars, and the “staid nobility of the countryside” (as he wrote in Chapter 3) by night. He drafted three chapters of Gatsby during the year-and-a-half he spent in Great Neck. But too much of his time and income went toward partying, and in 1924, he and Zelda took off for the French Riviera, where the peace, quiet, and exchange rate worked in their favor. There in France, he wrote the remaining six chapters in approximately six months. Sure, he was less distracted, but he also had a wealth of wealth-flooded experiences on which to draw, residences included. Matthew J. Bruccoli, the ostensible expert-in-chief on all things Fitzgerald, found that the word house is the most used noun in the novel—it appears 95 times.

If you Google “Gatsby house,” the first wave of links is to articles about Land’s End, a house once owned by Fitzgerald’s acquaintance, a newspaper magnate named Herbert Bayard Swope. Its bulldozing in 2011 earned many a headline, as it is said to have inspired the Buchanans’ Georgian mansion. But—sorry, New York Times, et al. —this was probably not the case. Sprawling and alabaster, it lacked the Buchanans’ “cheerful red-and-white” color scheme; on the far side of Sands Point, it was hidden from Kings Point’s view; and Swope didn’t buy the home until after the novel was published, so there is no evidence Fitzgerald ever went. However, a background check on Swope turns up definitive links not to Daisy but to Gatsby.

Photo courtesy of Oheka Castle

To give him some credit, Fitzgerald didn’t spend all of his nights going to parties. Some nights, he just watched them. His best friend in town, fellow writer (and drinker) Ring Lardner, lived next door to Swope’s first house, a large gothic-inspired home that Lardner described as hosting a “constant stream of parties.” For reasons unknown, 15 years after writing Gatsby, Fitzgerald scrawled his real-life sources for each of the chapters in the back of his copy of André Malraux’s Man’s Hope. For Chapter 3, the entirety of which is devoted to describing Nick’s first Gatsby party, what name should appear but the “Swopes.” Architecturally, there is nothing château-esque that aligns. But as a Dionysian headquarters, evidently it was wildly inspirational.

Speaking of parties, the most lavish of the Roaring ‘20s was held in 1924 at Harbor Hill, the home of Clarence H. Mackay. Well, home is a relative word. A popular architect of the time, Thomas Hastings, liked to preach that houses are half pudding and half sauce, i.e. half about the abode itself and half about all the accompanying accessories. Mackay really liked sauce. To name a sampling of all that his grounds included, there were two farms, a blacksmith, an auto repair shop, guesthouses, Turkish baths, shooting galleries, and a casino (because, when you have 648 acres to fill, why not?). As for the house itself, it was modeled primarily after the French Château de Maisons-Laffitte but also drew upon a couple of Hôtels de Ville. His pudding, that is, was the same as Gatsby’s—just a larger serving.

Fitzgerald and Zelda attended a party at Harbor Hill in 1923, but they were already in France by the time of the big blowout the following year. Held in honor of the Prince of Wales, the party featured two orchestras, fountains spouting perfume-infused water, and flower arrangements that magically floated in the middle of 300-pound blocks of ice. Rumor has it that the estate was so bright that it could be seen from Connecticut, which probably had something to do with the giant American flag made of light bulbs waving above the roof. Whether Fitzgerald was given the full detailed recap isn’t clear, as most of his published correspondences circa this time are with his editor, Maxwell Perkins, about matters pertaining to the novel. However, nearing the time of publication, Fitzgerald, who despised the title The Great Gatsby and toiled for months to think of something else, wrote to Perkins that he had finally found one: Under the Red, White, and Blue. Unfortunately, it was too late to change. Regardless, revelers reveling under the red, white, and blue in Mackay’s North Shore château seems awfully coincidental, unless Fitzgerald was in touch with his times to a psychic degree.

Harbor Hill was out-done only by Oheka Castle—excusable, considering Oheka is still the second largest private home in America and was conscientiously designed to one-up Mackay. Sitting on 443 acres, the castle was modeled after Maison Lafayette, which is essentially just a bigger version of Maisons-Laffitte, designed by the same French architect. Both even attempted to veil their newness with “a thin beard of raw ivy.” The triangulated roofs, elaborate stonework, and chimneys for 39 fireplaces are quintessentially French and reinforce the “period craze” of the 1910s, during which Gatsby’s house was theoretically built, if you use Fitzgerald’s context clues and do the math. Oheka was so period driven that it moved William Adams Delano, an architect of the caliber that gets immortalized in rare and gorgeous coffee table books (alongside his pithy quotes), to say, “Every owner wants to have a name for the style in which his house is built. I find this both difficult and annoying … [most people] are not satisfied with accepting a good house, well arranged, without a fancy name.”

Delano would have been particularly peeved by Winfield Hall, then, the estate of Frank Winfield Woolworth, an art lover who turned his upstairs hallway of bedrooms into an interior design timeline. Among them was the Ming Dynasty suite, Empress Josephine room, Marie Antoinette room, Napoleon room, and three different Louis—XIV, XV, and XVI. (For visuals, consult the coffee table book.) Gatsby, too, had “Marie Antoinette music-rooms and Restoration salons … period bedrooms swathed in rose and lavender silk and vivid with new flowers.” Woolworth’s library was wood paneled in French Gothic style. Gatsby, too, had a “high Gothic library, paneled with carved English oak, and probably transported from overseas.” And the music room, which occupied the entire west wing of the house, was lit with stage lighting, trimmed with gilded moldings—the humble milieu for a tremendous Aeolian organ. Gatsby, well, he had a piano. (Note: Baz Luhrmann does bless him with a full organ in the upcoming film.) Nevertheless, the men’s puddings had plenty of the same ingredients. Delano probably wouldn’t have been fond of Gatsby either.

Photo courtesy of Gabrielle Lipton

Another scholarly favorite when it comes to the Gatsby house-guessing game is Beacon Towers, originally designed by a widowed Vanderbilt and modeled after Blair Castle in Scotland. William Randolph Hearst bought it later on. Alva (said widow) traveled to see Blair and is said to have remarked, “My dear, my castle in Sands Point, U.S.A., is far more authentic!” Complete with turrets and a façade of off-white stucco so smooth that it looks Photoshopped even in grainy black-and-white pictures, Beacon was also authentic to its nickname, “Cinderella’s Castle,” and looks more akin to the backdrop of a fairy tale stage set than an actual home—an elusiveness that lends itself so well to the narrative of Gatsby. Like Harbor Hill, Beacon no longer exists. Only Oheka and Winfield remain to be visited.

And then there is Kings Point. Located at the end of what is now named Gatsby Lane, the property was first owned in 1851 by John Alsop King Jr., the well-endowed son of New York Gov. John Alsop King. During Fitzgerald’s time, it housed Richard Church of the Arm & Hammer Baking Soda clan. Most recently, the crumbling estate fell into the hands of an elderly widow, Marjorie Brickman Kern, whose family bought the property in 1951 and converted it to a family compound of small houses—not unlike Nick Carraway’s—dotting the property behind a formal manse sitting on the throne of the very tip of West Egg. Marjorie’s two sons, Russell H. Handler and Frederick John Handler, were the last men standing of the Brickman family, and in the mid-1990s, a family feud took shape as the brothers began to battle over their inheritance. Credit cards were exploited; tricks were played to inherit a great portion. And then one day in 2006, Jennifer Eley, the wife of John F. Handler, was found dead in the pool.

Photo courtesy of Gabrielle Lipton

The property continued to deteriorate until it was sold in April 2012 for much below its $39.5 million asking price, a fate similar to so many others of its kind. Nearly one-half of the homes that once gleamed along the Gold Coast were abandoned after the Great Depression and torn down by the ‘70s. Even for American royalty, triple-digit acreage and double-digit staffs were too much to fund forever. Like Gatsby’s “huge incoherent failure of a house,” they drowned in their own sauce. But there’s something sexy about this sad fate, too. The fewer clues left, the more the moneyed mystery of the Gatsby mansion begs to be solved.

Fitzgerald, of course, drew from many sources to create a spectacle that, when pulled apart, really did exist. But the full spectrum of all that the house reflected is still revealing itself, what with the shady pool murders and state of estates continually in flux. As if Fitzgerald was in touch with our times to a psychic degree, too, the recession did not spare the Gold Coast and left many dreamlike mansions ownerless—green lights in their own right that slip back out of reach with a single change of tide. Perhaps it’s not so much which mansion was Gatsby’s; it’s which one is destined to be the next.

*Correction, May 6, 2013: This article inaccurately referred to the village of Sands Point as part of Manhasset.