Beards, Theft, and Other Peculiar Factors That Turn Images Into Icons

A new book traces how images become universally recognized icons.

-

St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai.

St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai.How Christ Got His Beard

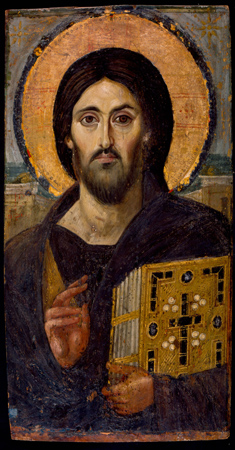

Images of Christ did not always have a beard or even a face. Initially, Christ was portrayed simply with symbols. When images in his likeness were finally introduced around the late third century, they depicted Christ as a youthful, nonbearded Apollo figure. Finally, during Constantine's rule of the Holy Roman Empire, Christ's image morphed into the modern one. "You needed an image that looked more ruler-like," Kemp explains. So Christ was painted to look more like a mature commander—hence the beard. This painting of Christ on Mount Sinai, created around the sixth century, is the standard image we recognize today.

-

Photograph courtesy Martin Kemp.

Photograph courtesy Martin Kemp.Cross Your Heart, Wonder Why?

Talk about a good PR spin: Every day, people around the world wear this symbol of violent death and sacrifice around their neck. The cross became an icon both because of Christ’s crucifixion and because it represents the four cardinal directions. The religious propagation didn't happen immediately, Kemp says, "because early Christianity [the first three centuries] didn't think that the image of a crucified figure was very promotional." But in the 300s, Roman Emperor Constantine developed the narrative of the cross as a symbol of power and faith after it supposedly guided him through battle. Kemp took this photo of crosses used in a funeral ritual near Santa Fe, N.M.: As mourners carry a coffin on the way to the cemetery, it's customary to stop at this resting place and stick a wooden cross into the ground.

-

Wellcome Library, London.

Wellcome Library, London.Queen of Hearts

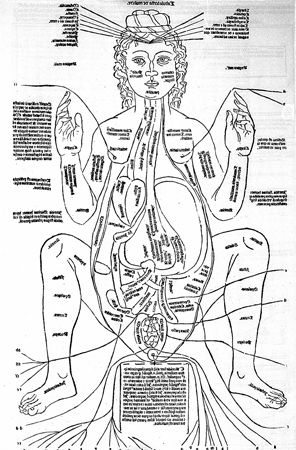

What does this squatting pregnant woman have in common with Milton Glaser's “I Heart New York T-Shirts?” Anatomical illustrations like this one (created in 1491 Venice) helped introduce the outline of today's heart shape. But the image really took off with playing cards, Kemp says; the modern suits of spades, diamonds, hearts, and clubs were first used in 15th-century France.

-

Sergey Skleznev/Alamy.

Sergey Skleznev/Alamy.Hollywood Loves Scary Lion Goddesses

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer didn’t put a roaring lion in its logo because the CEO liked jungle cats. It’s because the image of the lion is associated with power and royalty. That association originated with Sekhmet, a lion-headed goddess, in 1400 B.C. Egypt. Sekhmet (depicted by the statues here) was the most formidable of deities. She was "the mistress of dread, fierce and implacable," Kemp says. But reasons behind the lion’s grip on generations of imaginations “comes from something less tangible,” Kemp writes in the book. The Lion’s swagger, mane, and personality “all strike some kinds of deep-seated chords.” The cat’s spirit lives on in Beijing's former imperial palace in the Forbidden City, Disney’s The Lion King, and Edwin Landseer’s lions of Trafalgar Square in London.

-

Pascal Cotte.

Pascal Cotte.Why Theft Can Be Good for Stardom

How did a portrait of a bourgeois Florentine woman achieve such prominence? "I don't know of any painting which communicates in such an uncanny and strong way the sense of another person," says Kemp. "And it helps that it has an extraordinary story attached to it." When the artwork was stolen from the Louvre by Italian house painter Vincenzo Peruggia in 1911, the theft was a global news story. "That pushed the trajectory upwards pretty sharply," says Kemp.

-

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2011; image © ADAGP, Banque d'Images, Paris 2011.

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2011; image © ADAGP, Banque d'Images, Paris 2011.Black and Red All Over

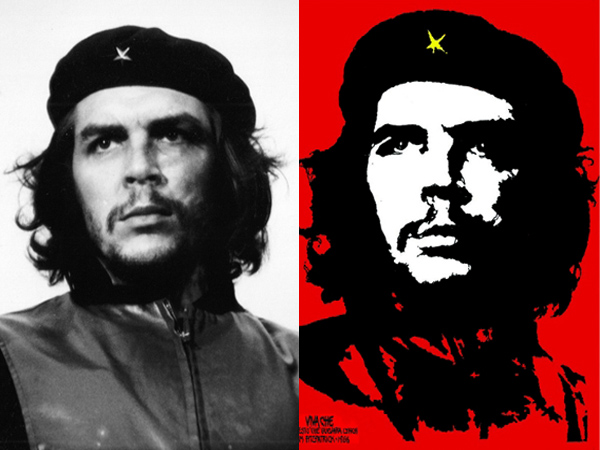

At first, the local Havana newspaper didn’t want to print photographer Alberto Korda’s picture of Che Guevara. Korda was photographing a memorial service for victims of the La Coubre freighter explosion in March 1960 when he took what would become the iconic shot of the Argentine revolutionary. Editors wanted a picture of Cuban President Fidel Castro and the French philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, also at the event. It wasn’t until Guevara’s martyr-like demise that the image took off internationally. In 1968, Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick famously converted the image into a black silhouette against a red background, transforming Guevara’s profile into a Christ-like image. But religious iconography wasn’t enough to make the picture omnipresent. “It entered at exactly the right time … during the youthful rebellion of the 1960s [in America and Europe],” Kemp says.

-

Press Association Images.

Press Association Images.The War Child

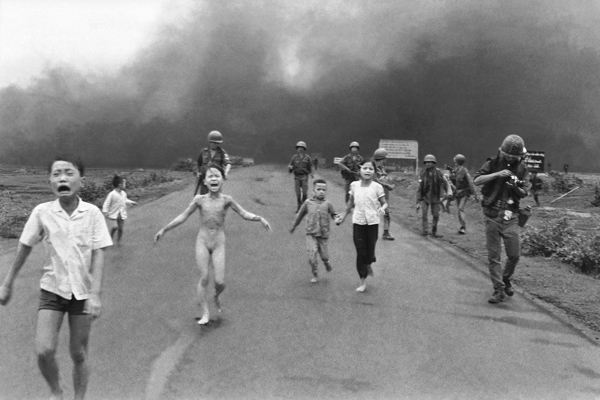

The naked girl in this image, Kim Phuc, is another Che Guevara, Kemp says. In other words, it’s a picture that became famous not only because of its extraordinary visual qualities, but also because of the story of its subject. Associated Press photographer Nick Ut took this Pulitzer Prize-winning shot during the Vietnam War in 1972 of 9-year-old Kim Phuc following a napalm attack. After attempting to hide from the photograph, Phuc ultimately embraced her iconic status. She even set up a trust for children victimized by war, and became a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador.

-

GV Art, London.

GV Art, London.I Pledge Allegiance to Human Skin

A century ago, Kemp says he would’ve chosen the British flag as the world’s most potent abstract symbol. But now, the British professor concedes that the award for most iconic banner design goes to the Yankees. The American flag is universally recognizable due in part to its complex design and because of the nation’s exponential rise to global superpower status during the 20th century, he says. Icons would not be icons if they weren’t constantly getting referenced and re-imagined. Here is a controversial interpretation of the flag by artist Andrew Krasnow. Made from human skin in 1990, it was meant to spark conversations about the napalmed girls and Native Americans who suffered so America could become a juggernaut.

-

Courtesy Norman and Linda Dean: image from Community Archives, Vigo County Public Library, Terre Haute, Ind.

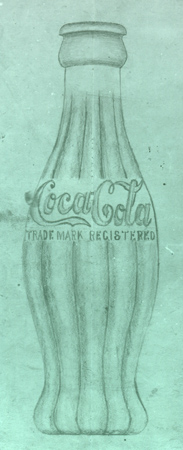

Courtesy Norman and Linda Dean: image from Community Archives, Vigo County Public Library, Terre Haute, Ind.Unmistakable Any Time of Day

When the Coca-Cola Company began brainstorming bottle designs for the eponymous beverage, they set two goals for the final product: It had to be recognizable in the dark and broken into pieces. The result? A svelte, ribbed-glass bottle, designed by Earl R. Dean for the company in 1915 (the original drawing is pictured here). The drink, which at one point contained cocaine, was a huge commercial success. “You would expect in normal commercial operation that the logo would change, the bottle would change,” Kemp says. “But it became such a symbol of Coca Cola that nobody would now dare change it. For a product design and logo to survive a century is just fantastic.”

-

A. Barrington Brown/Science Photo Library.

A. Barrington Brown/Science Photo Library.Double the Helix, Double the Fun

Unless you’re a scientist, chances are there aren’t too many diagrams you still remember from 10th grade biology. Except, of course, for the DNA double helix. In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick published an article in the journal Nature describing the double helical structure of DNA. The article sparked some discussion, but the structure didn’t achieve iconic status until Watson and Crick’s 1962 Nobel Prize. Today, “its ubiquity has been cemented by the search for the human genome, which has had a huge public impact,” Kemp says, pointing to the groundbreaking Nature article from 2001, which announced a draft of the human genome sequence. Here, the two men pose with their DNA model.

-

From CREDIT: Time magazine (July 1, 1946). 2011 Time Inc.

From CREDIT: Time magazine (July 1, 1946). 2011 Time Inc.A Scientific Formula Catchy Enough for Pop Culture

It’s on coffee mugs, T-shirts, and tote bags. Albert Einstein’s formula ascended from the annals of science to commercial pop culture because of the atomic bomb, and this 1946 Time magazine cover, Kemp says. This issue, published after the bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, transformed Einstein into a scientific saint and made his formula legendary. “He represented America as the home of free thinking, of people who were great pioneers of science,” says Kemp.

Jesus Christ was originally depicted without a beard. The heart symbol didn’t get its two round lobes until the 1400s, and the Coca-Cola bottle hasn’t changed in almost a century.

These are just a few of the interesting facts that Oxford University professor Martin Kemp encountered in the process of researching his latest project, Christ to Coke: How Image Becomes Icon. The book, which will be released Nov. 10, examines the stories behind the most famous pictures in the world.

"Where does the notion of an iconic image come from?" is the driving question behind this work. To find out, Kemp chose 11 of the world's most recognizable images in areas as distinct as biology and product design. The slide show above reveals his 11 picks, and a few of the most interesting factors that propelled their rise from obscurity to fame.