The Swollen Mississippi

-

Photograph courtesy of Dick Sevier.

Photograph courtesy of Dick Sevier.April-May 1897, southern end of Madison Parish, La.

The town of New Carthage, pictured here, no longer exists. Retired geologist Dick Sevier, who wrote a history of Madison Parish, thinks the flooding wiped it out.

-

Photograph courtesy of Dick Sevier.

Photograph courtesy of Dick Sevier.March-May 1912, downtown Tallulah, La.

The 1912 flood, which caused 250 people to drown and drove 30,000 from their homes, flooded the town of Tallulah even though it’s about eight miles from the closest part of the river.

-

Photograph courtesy of Dick Sevier.

Photograph courtesy of Dick Sevier.April-May 1922, near Madison Parish, La.

Sevier says this photo was taken in Duckport, a site on the Mississippi “just upriver from Vicksburg.” His mother’s family owned the Duckport plantation beneath the water in this photo. The man pictured, M.T. Young, was a well-known entomologist at the time.

-

Photograph courtesy of Dick Sevier.

Photograph courtesy of Dick Sevier.January-May 1927, Tallulah, La.

Until recently, this was the most devastating flood on the lower Mississippi River in recorded history. In some spots, the river’s overflow spanned 80 miles, submerging an area of about 26,000 square miles total. The destruction prompted the creation of the Flood Control Act of 1928, which mandated that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers build stronger levees and spillways to prevent future disasters. Herbert Hoover, then the secretary of commerce, called the flood “the greatest peace-time calamity in the history of the country.”

-

Photograph courtesy the Arkansas History Commission.

Photograph courtesy the Arkansas History Commission.February-March 1937, Hughes, Ark.

The floodwaters in the lower Mississippi River Valley tested the Bonnet Carre spillway, completed in 1931, for the first time. The spillway diverted water from the river out to Lake Pontchartrain. Twelve states, including West Virginia, Arkansas, and Louisiana, were still inundated. The Red Cross maintained camps for thousands of refugees.

-

Photograph courtesy U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Mississippi Valley Division.

Photograph courtesy U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Mississippi Valley Division.March-May 1973, Vicksburg, Miss.

These waters, in which 25 people drowned and another 35,000 were displaced, impelled the Army Corps to open the Morganza floodway—completed in 1954—for the first time. Doing so diverted water from the main waterway into the Atchafalaya Basin.

-

Photograph by Chris Wilkins/AFP/Getty Images.

July 1993, Davenport, Iowa.

This flood killed more than 40, forced evacuations of 54,000, and engulfed more than 20 million acres of land in nine states. The total economic cost was estimated to be about $18 billion, the equivalent of $28 billion in current dollars. Here, floodwaters storm and saturate downtown Davenport.

-

Photograph by Chris Graythen/Getty Images.

August 2005, New Orleans.

Hurricane Katrina’s deadly force breached levees in New Orleans and inundated about 80 percent of the city. It killed 1,836 people and damaged or destroyed 275,000 homes in the Mississippi River region. According to one estimate, the total economic loss could ultimately be more than $100 billion. Katrina remains both the costliest hurricane in U.S. history and the deadliest in 77 years. Canal Street is pictured here a day after Katrina ravaged the city.

-

Photograph by NASA Earth Observatory.

Photograph by NASA Earth Observatory.August 2005, New Orleans.

The surging waters spawned by Hurricane Katrina breached these levees. The top image depicts an 800-foot-long break in the Industrial Canal levee. The bottom image shows a rupture in the 17th Street Canal of about 475 feet. -

Photograph by Joe Raedle/Getty Images.

June 2008, Oakville, Iowa.

A 2008 flood killed two dozen people, injured 148, and forced around 35,000—plus at least three pigs—to evacuate from their homes.

-

Photograph by Joe Raedle/Getty Images.

June 2008, Oakville, Iowa.

The river burst 25 levees in Missouri, Illinois, and Iowa.

-

Photograph by Scott Olson/Getty Images.

May 2011, East Prairie, Mo.

This year, diverted waters from the levee at the convergence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers flooded about 130,000 acres of Missouri farmland and about 90 homes.

-

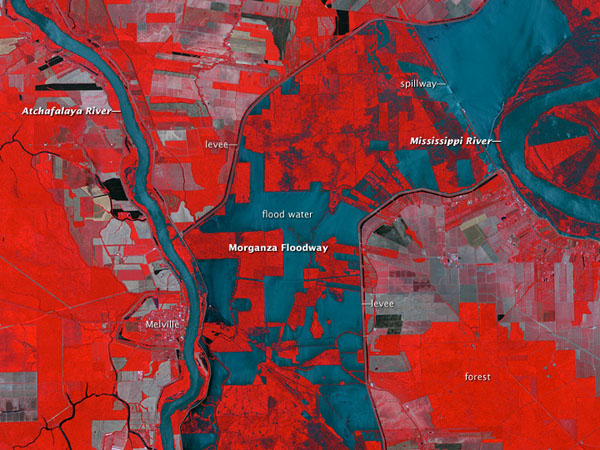

Photograph by NASA Earth Observatory.

Photograph by NASA Earth Observatory.May 2011, Louisiana.

Water gushed into a 15 to 20 mile region five days after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers opened bays to divert water onto the Morganza Floodway. Vegetation is red, clear water is blue, and sediment-heavy water is blue-gray. The gray swaths likely indicate burned or cleared farmland.