A Memorial for Ike

-

Photograph by Eric Wind for the National Civic Art Society.

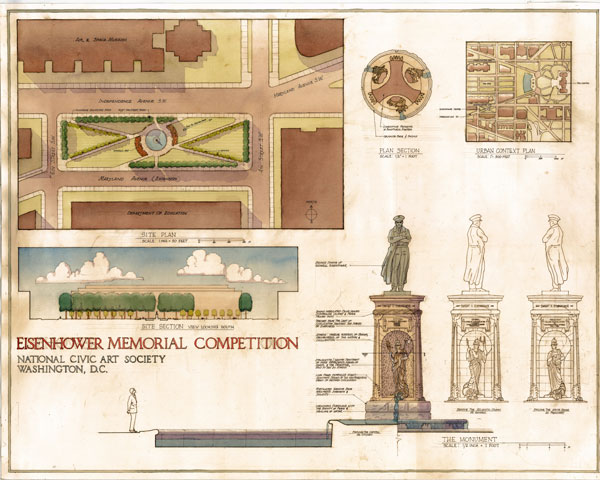

Photograph by Eric Wind for the National Civic Art Society.An Eisenhower Memorial: Milton Grenfell’s design

This spring, the National Civic Art Society and the Institute for Classical Architecture held a competition for a memorial to Dwight D. Eisenhower. Since an Eisenhower memorial is currently being designed by Frank Gehry in Washington, D.C., the competition was intended as a counterproposal, more specifically, a classical counterproposal. Milton Grenfell’s entry, for example, consists of a sculpture of the president in military garb, standing on a three-sided limestone pedestal. Each side of the pedestal represents one aspect of his life—citizen, general, and president. The three Athenas hold different symbolic objects, a hoe, a spear and a laurel wreath, and the Constitution. Water falls from the cornucopias below the statues into a pool surrounding the pedestal; the rest of the site is treated as a green square. While the symbolism may strike some as excessive, the memorial has an attractive small scale. The common objection to such a design is that it is not modern. Eisenhower was a modern man, shouldn’t he be remembered in a modern way? And what would that way be?

-

Courtesy of www.eisenhowermemorial.org.

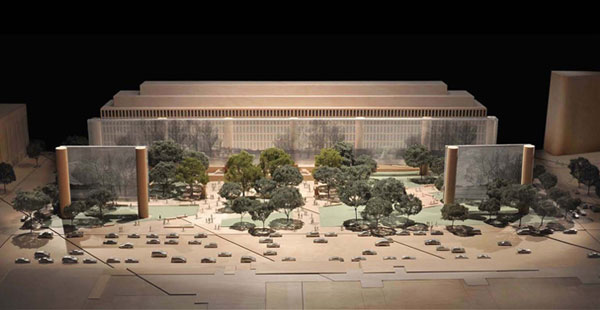

Courtesy of www.eisenhowermemorial.org.An Eisenhower Memorial: Frank Gehry’s design

Gehry’s answer to that question (his design is still evolving) is grander than Grenfell’s. Two rows of massive limestone columnlike shapes define the edges of the 4-acre site between the Department of Education building and the Air & Space Museum. Columns are a traditional memorial device, although 80-foot columns are big, even for Washington, and seem out of keeping with Ike’s plainspeaking character. More controversial are the woven stainless-steel mesh screens—Gehry calls them tapestries—carrying as yet to-be-determined images, stretched between the columns. Eisenhower will likely be remembered a long time; a Wikipedia aggregate of presidential rankings has him at No. 8 (higher than any president since), and as a World War II military leader his position in history is secure, but what will be the impact of the enormous screens, 50 years from now—or 100? Will they help people recall the five-star general who became president, or will they merely remind them of a billboard?

-

Witold Rybczynski/CREDIT: Slate.

Witold Rybczynski/CREDIT: Slate.WWI Memorial

“It’s a risky thing to try and speculate on what future generations are going to think,” Susan Eisenhower, the president’s granddaughter, told the members of the National Civic Art Society, “because we simply don’t know.” She’s right. Over time, old memorials often lose their meanings—or acquire new ones. Most visitors to the Mall don’t immediately recognize this little tempietto (left) as a commemoration of the 499 citizens of the District of Columbia who gave their lives in World War I. Or that this little structure is a bandstand, designed to hold the entire Marine Corps Band, which (conducted by John Philip Sousa) played at the memorial’s dedication in 1931. You can learn some of this by reading the inscriptions, but whether you do or not, this is still a handsome structure that communicates an important message: We Cared. Perhaps that is enough.

-

Photograph by Sue Beaumont for ADAM Architecture.

Photograph by Sue Beaumont for ADAM Architecture.Atlanta’s Millennium Gate

The District of Columbia Memorial is 80 years old, but its architecture still speaks to us. That is the advantage of traditional commemorative forms such as obelisks, columns, and statues—they have been around a long time. Roman triumphal arches, for example, which date back to the Arch of Titus and the first century, have proved remarkably durable. Nineteenth-century versions were built in London, Munich, and, of course, Paris. The first American memorial arch was built in Hartford in 1879, and others followed in New York’s Washington Square and Valley Forge. Famous gates include the Brandenburg Gate (1791), the Gateway of India (1924), and the Gateway Arch in St. Louis (1965). The latest version is the Millennium Gate in Atlanta (left), completed in 2008. The 73-foot limestone structure was designed by Hugh Petter of the British firm, ADAM Architecture. The allegorical bronze figure in the foreground, representing peace, is one of an eventual six created by the Scottish sculptor Alexander Stoddart.

-

Witold Rybczynski/CREDIT: Slate.

Witold Rybczynski/CREDIT: Slate.Henry Merwin Shrady’s Ulysses S. Grant sculpture

Statues work well as monuments since they can be appreciated aesthetically, even after their commemorative function has receded. For 16th-century Florentines, for example, Michelangelo’s David was a political allegory of the republic’s defense of civil liberties; for us it’s strictly art. Ulysses S. Grant’s star has dimmed since his large memorial at the foot of the U.S. Capitol was dedicated in 1922. (Wikipedia ranks him lower even than Nixon.) Yet Henry Merwin Shrady’s equestrian sculpture remains a moving work. The man on the horse sits gazing at the distant Lincoln Memorial, imperturbable, rock-steady, the wind at his back—ignoring the tourists below, as they ignore him.

-

Witold Rybczynski/CREDIT: Slate.

Witold Rybczynski/CREDIT: Slate.Korean War Veterans Memorial

The Korean War Veterans Memorial on the Mall includes larger-than-life stainless steel sculptures of servicemen on patrol. The figures represent each branch of the military: GIs, Marines, a Navy corpsman, and an Air Force forward air observer. All are correctly depicted and carry a variety of weapons and equipment. Yet the figures are more like mannequins than art—inexpressive, lumpish, and crude. I doubt that the Korean War will loom large in the national memory 100 years from now, and unlike Shrady’s memorial, this one will offer little in the way of aesthetic satisfaction.

-

Chris Greenberg via Wikipedia Commons.

Chris Greenberg via Wikipedia Commons.Pentagon Memorial

Future visitors to the Korean Memorial will at least recognize the figures as soldiers, but what will they make of the Pentagon Memorial? The challenge for abstract memorials is to make sure that the language of today communicates with the future. Traditionally, monuments used widely accepted conventions: Palm branches signified peace, a spear stood for war, a horse for nobility. As long as this language survived, so did the commemorative messages. But the Pentagon Memorial follows no universal conventions. The 184 benchlike objects—why benches?—each commemorates a victim, and are arranged parallel to the trajectory of Flight 77; some face one way and some the other, signifying whether the individual died on the plane, or in the building. They are further organized according to the birth dates of the victims, their ages being reflected in the height of the encircling wall. This memorial language is entirely private, an invention of the designers, and its obscure meanings are unlikely to endure. The only conventional image that comes to mind is of a rather bleak cemetery.

-

Hu Totya via Wikipedia Commons.

Hu Totya via Wikipedia Commons.Vietnam Veterans Memorial

“Lest We Forget” has appeared as an epitaph on many memorials since Rudyard Kipling wrote it in a poem in 1897. President Obama was less tentative when on the anniversary of 9/11 he told his audience, “When we say we will never forget, we mean what we say.” But we do forget. The 58,000 names on the wall of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, for example, will always be a reminder of personal sacrifice, just like the memorial to the missing World War I dead at Thiepval. But will the Vietnam Memorial sustain its current emotional power when the war itself, like other distant wars fought for obscure reasons, recedes from memory, or will it acquire a new meaning? When the Washington Monument was completed in 1884, it was criticized for its lack of imagery and inscriptions—it does not even bear the president’s name. This ambiguity turned out to be an asset, although exactly what the giant obelisk symbolizes is hard to say: a presidential memorial, an urban landmark, a national icon, or all three?

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski/CREDIT: Slate.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski/CREDIT: Slate.Ivor Roberts-Jones statue of Winston Churchill

What about Ike? Columns and woven screens aside, it’s difficult to commemorate an individual without a figural representation—that is, a statue. The designer of a memorial to Eisenhower could do worse than look at a British memorial to another significant Second World War figure: Winston Churchill. The 12-foot bronze by Ivor Roberts-Jones in Parliament Square, Westminster, portrays a brooding wartime prime minister, enveloped in a military-style great-coat that emphasizes his stubborn immobility. While the idea of a monumental figure is traditional, the pose with a walking stick is demonstrably modern, as is the simple stone plinth, which carries a single inscription: “CHURCHILL.” No dates, no quotations, no explanations, no symbolic reminders of his many achievements. Most recent American memorials are both too large and laden with too much information. This relatively modest monument feels just about right.