A Dazzling New D.C. Office Building

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.In the early 1900s, architects such as Daniel Burnham (Union Station), John Russell Pope (National Gallery and Jefferson Memorial), and Charles Adams Platt (Freer Gallery) did some of their best work in Washington, D.C. But with rare exceptions, first-rank Modern buildings in the capital were few and far between; Modern architects seemed intimidated or stymied by the capital. Perhaps that's why for a long time, the most interesting Modern building was outside the city: Eero Saarinen's Dulles Airport. Home-grown D.C. architecture is still uninspired, but buildings by outsiders such as Norman Foster, whose undulating glass roof covers the courtyard of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and National Portrait Gallery, and Moshe Safdie, whose U.S. Institute of Peace is due to open this spring, are raising the bar. Last year, Foster's old partner, Richard Rogers, completed an office building in the shadow of the Capitol dome. In a city overflowing with office buildings, it's a doozy.

-

Image by CREDIT: NCinDC.

Image by CREDIT: NCinDC.Rogers was asked to expand what was originally the headquarters of the venerable Acacia Life Insurance Co. (right), which was designed in 1935 by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, the architects of the Empire State Building. Like the Empire State, the six-story Acacia Building is an example of American early Modernism, a blend of Neoclassical planning—Shreve and Lamb both apprenticed with Carrère & Hastings—practicality, and a touch of Art Deco sensibility. This plain, geometric style, also visible in the late work of Raymond Hood and Paul Cret, is very different from the International Style of European Modernists, who would never have adorned the entrance to a building with a pair of stylized griffins. The sculptures are the work of Edmond R. Amateis, who designed the bronze doors on the west facade of the U.S. Capitol.

-

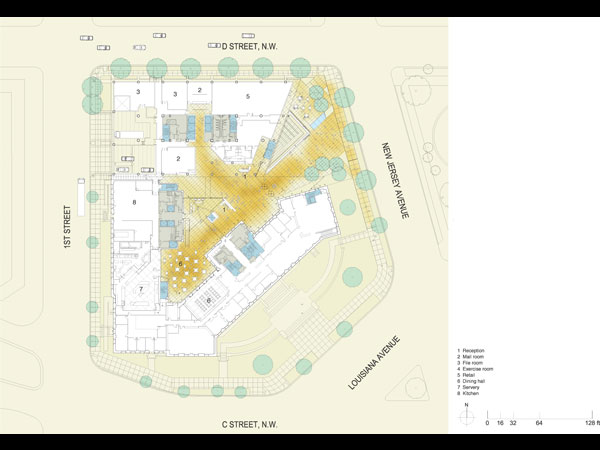

Image courtesy Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners. © Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

Image courtesy Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners. © Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.The floor plan shows how skillfully William Lamb accommodated the Acacia Building (on the lower right, facing Louisiana Avenue) to the odd-shaped site created by the intersection of Louisiana with C Street and New Jersey Avenue. The seven-story wing along First Street is a 1953 addition. The new project involved demolishing a parking structure that stood on the north edge of the site, and replacing it with six levels of underground parking and a new 10-story office building (which is said to command the highest rents in the city). The triangular courtyard between the three buildings was turned into a glazed atrium, housing the lobby as well as a staff dining area. The entrance is across a plaza that also functions as a terrace for a projected café.

-

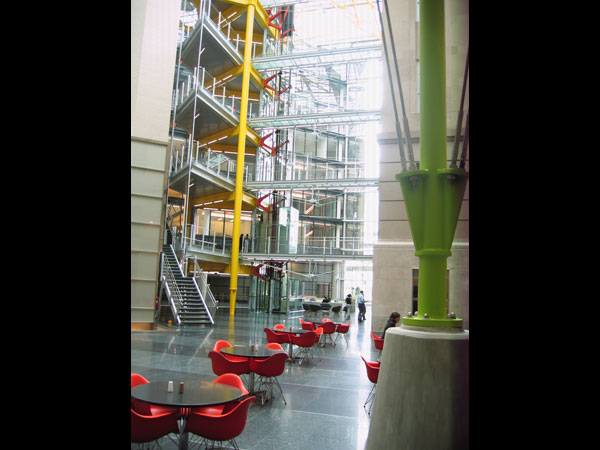

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The Acacia Building, the 1953 wing, and half of the new building are today occupied by the international law firm Jones Day. The staff circulates between the different offices on glass footbridges that intersect in a series of elevated platforms in the center of the atrium. The platforms sit within a yellow structure supporting a glass roof that hovers over the three buildings like a giant umbrella. The idea of high-powered lawyers hanging out in a steel tree house is typical of the laid-back organization of this distinctly non-white-shoe building.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The new building has several energy-conserving features. The bridges and platforms between the buildings have local heating and cooling that don't attempt to control the temperature of the atrium as a whole, which is air-conditioned only in the hottest summer months, and relies on operable glass louvers and old-fashioned fans for natural ventilation during the spring and fall. Since the tall space acts as a thermal buffer to the office building, it gets by with only single-glazing—cheaper as well as simpler. The glass roof of the atrium is made of "low E" coated glass with ceramic frits to reduce heat gain from the sun. A landscaped "green" roof on the 1935 building provides a terrace with spectacular views of the dome of the U.S. Capitol.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.Ivan Harbour was the director in charge at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, and Dennis Austin was project architect. It is 45 years since Rogers and Foster designed Reliance Controls, and more than 30 since Rogers and Renzo Piano worked on the Centre Pompidou , but while Foster and Piano have moved on, Rogers's firm has stayed true to its high-tech roots: structural daring, bright colors, exposed technology (the workings of a glass-cab elevator, right), and an airy sense of lightness. Precision is a hallmark of high tech, but here precision is accompanied by a kind of rough-and-ready brashness that recalls the heroic architectural Modernism of the 1920s. Painted steel, bare concrete, structural struts, and exposed plumbing blended into one kinetic whole.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.Considering that the United States is the world's industrial society par excellence, it has always baffled me that the kind of constructional prowess exhibited by this building is almost entirely the preserve of non-Americans: Rogers, Foster, Piano, Grimshaw. There is something old worldish about this kind of architecture, not simply the exacting way it's made, but also the way it exhibits an abiding faith in the value of craftsmanship. To understand the difference between this attitude and that of most American architects, compare the Rogers project with the nearby Newseum, designed by the Polshek Partnership, whose use of technology seems stagy and contrived by comparison.

-

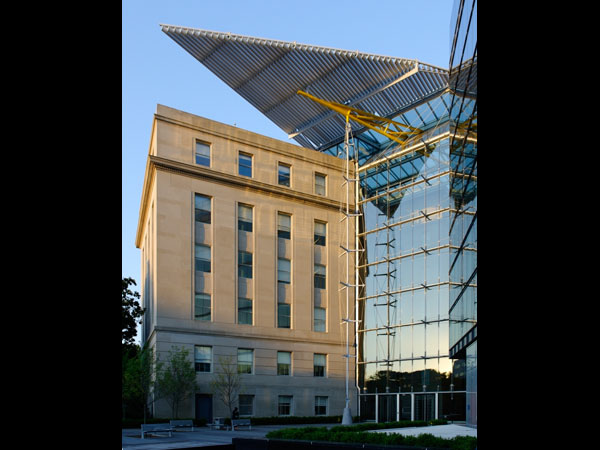

Photograph by Chuck Choi. © Chuck Choi.

Photograph by Chuck Choi. © Chuck Choi.A dramatic projecting sun-shade signals entrance to the building. The triangular roof sits on a projecting yellow truss that is supported, in turn, by what looks like a giant yacht mast. The seven-story, 6-inch-diameter steel pipe is stiffened by outriggers and tensioned cables. (Since this photograph was taken, the mast has been painted bright green.) Such structural high jinks are light years away from Shreve, Lamb & Harmon's orderly limestone facade. "That was then, this is now" seems to be the Rogers philosophy. Contrasting new and old is an architectural cliché that often leaves the old in its dust, but that's not the case here. One comes away admiring both buildings. Much has changed in 75 years, but not the sense of conviction that is the accomplished architect's hallmark.

Next: A Washington Renaissance Part 2: Bing Thom's Arena Stage Theater.