The Godfather of American Architecture

-

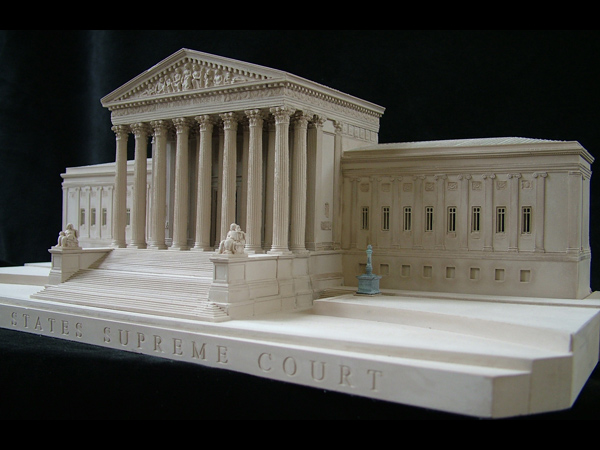

United States Supreme Court. Model by Timothy Richards, Bath, England.

United States Supreme Court. Model by Timothy Richards, Bath, England.Like so many public buildings in the nation's capital, the U.S. Supreme Court has fallen victim to the cultural vandalism of security consultants. To accommodate the space needed for visitor screening, the court recently announced that the grand main entrance in the portico at the top of 34 marble steps would be closed. Access will now be via a side door. Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, objected and expressed the hope that "the public will one day in the future be able to enter the court's Great Hall after passing under the famous words EQUAL JUSTICE UNDER LAW." This architectural icon—for once the word is apt—was designed by Cass Gilbert in 1935, but the inspiration for its columned portico is several hundred years old—the work of the Renaissance master Andrea Palladio. A model (right) of the Supreme Court is included in the Morgan Library’s current exhibition on Palladio, who turns out to be the godfather of American civic architecture.

-

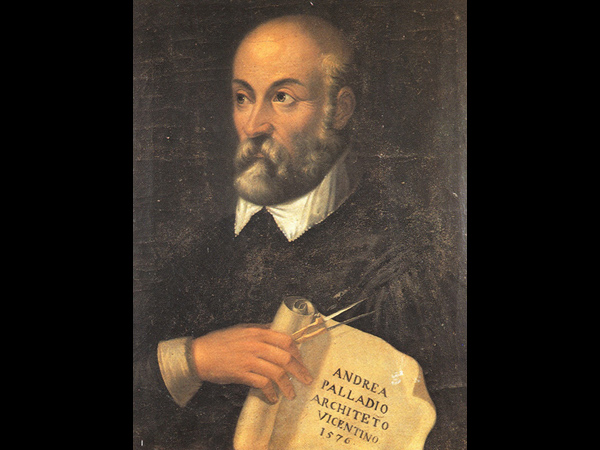

CREDIT: Ritratto di Palladio, G.B. Maganza, 1576. This image is in the public domain.

CREDIT: Ritratto di Palladio, G.B. Maganza, 1576. This image is in the public domain.Andrea Palladio (1508-80) lived and worked in the Venetian Republic. He designed several prominent churches in Venice, notably San Giorgio Maggiore, whose tall marble facade is visible across the water from the Piazzetta near St. Marks Square. Palladio began his career by designing villas on the Veneto mainland, and it was in these relatively modest buildings that he first used his signature architectural device, a Classical temple front. Thanks to Palladio's genius, and his widely distributed handbook, The Four Books on Architecture, the designs of his country houses greatly influenced architects in England, from whom his ideas migrated to America.

-

The West Building of the National Gallery of Art. Photograph by Gryffindor, 2007, via Wikipedia. This image is in the public domain.

The West Building of the National Gallery of Art. Photograph by Gryffindor, 2007, via Wikipedia. This image is in the public domain.The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., is much larger than anything Palladio ever built, but it likewise owes a debt to the 16th-century architect. Not only is the portico marking the entrance Palladian but also the flat dome that recalls the architect's reconstruction of Roman baths as well as his famous Villa Rotonda. Since the galleries of the museum are lit entirely by skylights, the architect, John Russell Pope, pulled off the not-inconsiderable trick of designing a block-long building without a single window. A big box, indeed.

-

The New York Stock Exchange. Photograph by Kowloonese, 2004, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

The New York Stock Exchange. Photograph by Kowloonese, 2004, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.By 1941, when the National Gallery opened, the tradition of using Classical porticos to indicate important buildings was already well-established. When George B. Post designed the New York Stock Exchange in 1901, he adopted a technique pioneered by Palladio: If you didn't have space—or the functional need—for an entry porch, you could create the illusion of a portico by pasting a temple front onto the facade. As Palladio often did, Post also played with building scale, in this case making the giant columns rise the full height of the nine-story building. The effect was to magnify the scale of the Stock Exchange and create an imposing presence within the narrow confines of Wall Street.

-

View of the North Portico and North Lawn of the White House. Photograph by Ed Brown, 2005, via Wikipedia. This image is in the public domain.

View of the North Portico and North Lawn of the White House. Photograph by Ed Brown, 2005, via Wikipedia. This image is in the public domain.The White House is the most iconic building in America. Designed by the Irish architect James Hoban in 1792, the design was based on a mansion in Dublin. The composition, proportions, the projecting portico (which Hoban added later), and the minimal decorations, mark it as Palladian. Because the porous sandstone walls of what was originally known as the President's House were painted with a protective coating of whitewash, people started calling it the "white house," a name formally adopted by Theodore Roosevelt in 1901.

-

Jefferson's design for the President's House. Model by Timothy Richards, Bath, England.

Jefferson's design for the President's House. Model by Timothy Richards, Bath, England.George Washington, no mean architect himself, selected Hoban's design for the President's House in a competition in which Thomas Jefferson also participated. Jefferson's design was based on the Villa Rotonda, one of Palladio's most copied works: a square block with four identical porticos and a domed central room. Jefferson enlarged the plan to accommodate the needs of an executive mansion and added a dramatic feature: glass panels in the dome. At night, they would have made the house into a presidential beacon.

-

Monticello. Model by Timothy Richards, Bath, England.

Monticello. Model by Timothy Richards, Bath, England.Like Washington, Jefferson was an accomplished architect. He owned a copy of The Four Books on Architecture, and when he began designing his house at Monticello, he incorporated the two-story portico of the master's Villa Cornaro. This type of portico was a favorite Palladian motif of Colonial American builders and was familiar to Jefferson, who had never been to Venice, from the Capitol at Williamsburg, Va. The model at right shows the house that he started to build at Monticello in the 1770s, before he changed his mind, demolished the upper floor, and built the familiar domed structure that appears on the reverse of the 1946 American nickel.

-

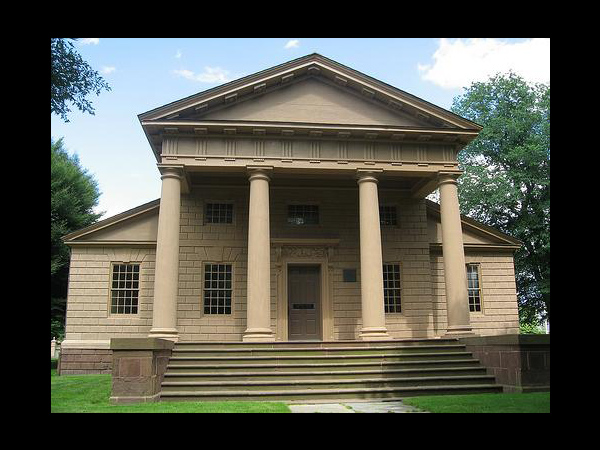

CREDIT: Redwood Library, a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial Share-Alike (2.0) image from herzogbr's photostream.

CREDIT: Redwood Library, a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial Share-Alike (2.0) image from herzogbr's photostream.The first American public building to incorporate the Palladian temple front is generally considered to be the Redwood Library in Newport, R.I., designed by Peter Harrison in 1749. Harrison, a part-time architect, found his model in a pirated edition of The Four Books on Architecture that was widely used by Colonial builders. The central pediment (or gable end) over the portico and the flanking half-pediments are a motif that Palladio invented and used in churches such as San Giorgio. The material of the library is wood made to look like masonry, which may seem odd until one remembers that many of Palladio's buildings were plastered brick scribed to resemble stone.

-

Mount Airy, main house. Image courtesy CREDIT: Jeffrey E. Klee, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Mount Airy, main house. Image courtesy CREDIT: Jeffrey E. Klee, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.Palladio's country houses provided useful examples to Colonial America. The grandest plantation house in Virginia was Mount Airy in Richmond County, built by John Tayloe in the 1750s, architect unknown. Mount Airy is based on an early design of Palladio's, in which the temple-front portico is more hinted at than fully expressed. Tayloe was wealthy enough to build not in wood (as Washington did at Mount Vernon) but in sandstone.

-

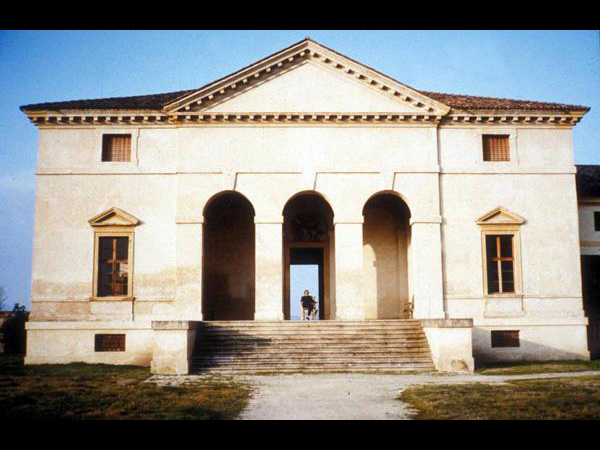

Villa Saraceno. Image courtesy Witold Rybczynski.

Villa Saraceno. Image courtesy Witold Rybczynski.What is it that has made Palladio so attractive to Americans over the centuries? Initially it was the desire of Colonial builders to adopt the latest British fashion—Palladianism—and the availability of plans in architectural handbooks that could be easily copied (since there were few trained architects). But it was more than that. Palladio combines practicality with grandeur (as seen in his Villa Saraceno, right), which particularly appealed to American sensibilities. Since Palladio's designs could be achieved in a variety of materials, and with a variety of means—grand and modest—they particularly suited a democracy. And Roman allusions fitted the new republic. Lastly, Palladio's architecture is never shy; it speaks directly and loudly but always in a humane voice. That appealed, too. It still does.