Nice Try

-

Photograph by Matthew Bisanz, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

Photograph by Matthew Bisanz, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2."A work of art, architecture, whatever it is, needs time to finally make a judgement as to whether it's right or not," says I.M. Pei in First Person Singular (1997), Peter Rosen's fine documentary about the architect. It is a cruel irony that after 30 years, what many consider Pei's greatest work, the East Building (right) of the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., has gone seriously wrong. The Tennessee marble panels that cover the exterior are coming loose, and the gallery has announced that all 16,200 panels will have to be reinstalled, at an estimated cost of $85 million. According to the Wall Street Journal, the failure probably has to do with the inability of the extremely thin joints to accommodate the expansion of the marble. It appears that Pei's uncompromising minimalist design pushed construction technology beyond its capacity. Such failures are not unheard of in modern architecture. Buildings sometimes fail because of incompetence or shoddy workmanship, but the examples that follow failed for a different reason: architectural ambition.

-

The Hancock Tower, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

The Hancock Tower, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.Hancock Place in Boston, designed by I.M. Pei & Partners between 1965-72, gives the impression of a minimalist glass sculpture. Even before the 60-story skyscraper opened, the glass proved problematic: Windows started blowing out during high winds. Eventually, so many shattered windows had been boarded up with plywood that Bostonians took to calling the city's tallest building the "Ply in the Sky." The sheets of mirrored double-layered glass, which make the building look like an elongated crystal, were the largest ever installed in a high-rise building. They failed not because of wind but because the outer layer, which had been given a reflective coating to produce the desired mirrored effect, expanded differently from the inner layer. The Hancock is striking because it is extremely narrow, which also turned out to be a problem, one that required adding extra structural steel and a damping mechanism to control the excessive swaying. In the end, the construction cost doubled, and everybody sued everybody. The case was finally settled out of court, another example of the perils of pushing the limits of building technology.

-

Photograph by Elisabetta Carattin. © Elisabetta Carattin. All rights reserved.

Photograph by Elisabetta Carattin. © Elisabetta Carattin. All rights reserved.Pushing technological boundaries has a long history in modern architecture; after all, in the 1920s, even flat roofs were risky. That didn't stop Le Corbusier, who made flat roofs a signature of the International Style. He also proposed hermetically sealed buildings with mechanical ventilation and exterior walls consisting of two layers of glass, with hot or cold air circulated in the space between the panes. Willis Carrier had successfully installed air-conditioning in a Brooklyn building almost three decades earlier, but the technology was still a novelty in Europe. In 1929, Le Corbusier had a chance to test his idea in the Cité de Refuge, a Salvation Army hostel in Paris. The building still looks remarkably modern, but it performed poorly. Budgetary constraints limited the south-facing wall to a single layer of glass, and the air-cooling was so inadequate that during the first summer the interiors became unbearably hot, and the alarmed public health authorities ordered openable windows installed.

-

Photograph by Jack E. Boucher, via Wikipedia. This image is in the public domain.

Photograph by Jack E. Boucher, via Wikipedia. This image is in the public domain.Frank Lloyd Wright also experimented—with underfloor radiant heating, skylights made of welded glass tubing, and ingenious low-cost construction systems of wood and concrete. Some of the experiments worked; many didn't. Wright had briefly studied civil engineering, but his ideas about structures were intuitive rather than formally learned. According to architectural historian Franklin Toker, Wright's assistants often beefed up the reinforcing steel in his designs without his knowledge. Wright had structural successes, like Tokyo's Imperial Hotel, which withstood a large earthquake, but also many failures, usually evidenced by drooping cantilevers. The most dramatic example is his famous house Fallingwater (right), whose "floating" balconies, which provide the building its drama, started to sag almost immediately after the building was completed in 1937. In 2002, ultrasonic testing revealed that the design of the reinforcing steel in the cantilevered structure was inadequate and the balconies would eventually collapse. The floors were removed, and the beams were reinforced with post-tensioned cables.

-

The Pruitt-Igoe project, via Wikipedia. This image is in the public domain.

The Pruitt-Igoe project, via Wikipedia. This image is in the public domain.The most notorious failure of modern architecture was not structural but ideological. In the 1950s, when federal funds became available for urban renewal and public housing, architects and planners thought they had the answer—what Le Corbusier called the Radiant City: megablocks with standardized apartment buildings surrounded by parkland instead of traditional streets and rowhouses. Soon tens of thousands of poor people were housed in these utopian communities. Except they weren't utopian at all. Not only did putting poor families in high-rise apartments prove to be a bad idea, so did concentrating poverty. Vandalism, crime, and drugs flourished. The housing agencies, which had done a poor job of managing, maintaining, and policing the projects, finally simply gave up. In what would become common practice, the 33 apartment buildings of the Pruitt-Igoe project in St. Louis (right), which had been conceived by Minoru Yamasaki, who would later design the twin towers of the World Trade Center, were dynamited. The buildings were less than 20 years old.

-

Photograph by Mikhail Klassen, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

Photograph by Mikhail Klassen, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.The design of a successful modern concert hall depends on a creative collaboration between the architect, the acoustician, and, of course, the client. When Lincoln Center's Philharmonic Hall opened in 1964, it was evident that something had gone seriously wrong. In short, the acoustics were exceedingly poor. Max Abramovitz, the architect, had paid more attention to the exterior than the interior; Leo Beranek, the acoustician, did not make himself sufficiently heard; and the Lincoln Center building committee acted wilfully and ignorantly in making budget cuts and last-minute changes to the design. After five attempts to solve the acoustical problems, drastic measures were taken: In 1976 the hall was gutted and rebuilt. Philip Johnson worked with acoustician Cyril M. Harris to lower ceilings, change the slope of the floor, and alter the stage enclosure. The result, renamed Avery Fisher Hall (right), was an improvement—at least the musicians could hear themselves play—but hardly a resounding success. In 2005, Lincoln Center approved plans by Foster + Partners to redesign the hall, yet again.

-

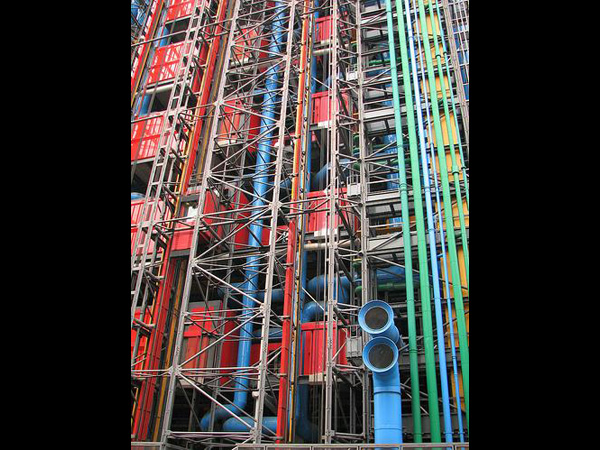

Photograph by Francesco Dazzi. © CREDIT: Francesco Dazzi. All rights reserved.

Photograph by Francesco Dazzi. © CREDIT: Francesco Dazzi. All rights reserved.The Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris opened in 1977 to great acclaim, yet less than 20 years later the building was closed for a major overhaul. The French authorities claimed that it was just a question of normal wear and tear due to intensive use of the extremely popular museum. But the refurbishment took three years and cost almost half of the original construction cost, so it's hard not to see this as a major building failure. The neophyte architects, Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, created a strikingly novel design by exposing not only the structural trusses and beams but also elevators, stairs, and a maze of pipes and ducts. That turned out to be not such a good idea, even in the relatively benign Parisian climate. Neither Rogers nor Piano, who went on to have distinguished careers, ever did anything quite so rash again.

-

The Millennium Bridge, via Wikipedia. This image is in the public domain.

The Millennium Bridge, via Wikipedia. This image is in the public domain.The team that designed the competition-winning entry for the Millennium Bridge across the Thames included not only architect Norman Foster and sculptor Anthony Caro but also Arup, the world's leading engineering firm. The design was required to have an extremely low profile, resulting in a sort of horizontal suspension bridge. Yet only three days after it opened, the footbridge had to be closed. The problem was that bridge designers are used to dealing with simple moving loads such as cars or trains. A person walking (and this bridge carries up to 2,000 people at a time) transfers his weight from one foot to the other, creating a sideways motion. The flexible Millennium Bridge picked up this motion, and as the bridge swayed, pedestrians swayed in step with it, which further accentuated the movement. It took almost two years to design and install the dampers that solved the problem of what Londoners were now calling the Wobbly Bridge.

-

MIT's Stata Center, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

MIT's Stata Center, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.When the Stata Center at MIT opened in 2004, Frank Gehry's idiosyncratic design reminded many people of a building coming apart at the seams. Three years later, that impression was reinforced when the university sued the architect and the contractor for design and construction failures, citing not only persistent leaks but also a cracking outdoor amphitheater, moldy brick, and snow and ice cascading dangerously from sloping surfaces. Robert Campbell, the Boston Globe's architecture critic, pointed out that MIT should have known what they were getting into: "You know if you hire Frank Gehry there are going to be new kinds of problems," he pointed out. But aren't architects—even great architects—supposed to solve problems, not create them?

-

Photograph by Ray Tsang, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 2.0.

Photograph by Ray Tsang, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 2.0.The $110 million addition to the Denver Art Museum was intended to attract attention, and it has, not because of its outrageous shape, designed by Studio Daniel Libeskind, but rather because of its outrageously leaky roof. The leaks—a serious problem in an art gallery—started immediately after the building opened in 2006, and repair work has continued every summer for the last three years. The work has included resurfacing parts of the roof, rebuilding parapet walls, and modifying skylights. According to a local television station, the city, which owns the building, and the contractor are currently engaged in a mediated negotiation to decide who will pay for the repairs—and who is to blame. You might have thought that Denver's heavy snowfall would have tempered the architect's penchant for unusual—and untested—forms, but the search for novelty, encouraged by an admiring public and indulgent clients, evidently prevailed over caution. Yet building remains intrinsically conservative in nature, the tried and true taking precedence over the untried and new. Experiments belong in the laboratory, not on the construction site.