A Museum of African-American History

-

Photograph by Andy Dunaway/USAF via Getty Images.

Photograph by Andy Dunaway/USAF via Getty Images.If the Mall in Washington, D.C., is the "nation's lawn," then the institutions that line it must be the national lawn ornaments. It is a motley architectural collection, ranging from standouts such as John Russell Pope's National Gallery of Art and I.M. Pei's East Building to the distinctly pedestrian museums housing natural history, American history, and "air and space." There are at least two garden gnomes (the Smithsonian "Castle" and the polychrome Arts and Industries Building), a concrete birdbath (the Hirshhorn), and even a pink flamingo (the National Museum of the American Indian). This heterogeneous assortment is not what the designers of the Mall, Charles Follen McKim and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., had in mind, but the result is actually appropriate for a large and varied democracy. Two weeks ago, the Smithsonian announced an architect to design the National Museum of African-American History and Culture, the latest addition to this display. Is it a nymph, a gnome, or another flamingo?

-

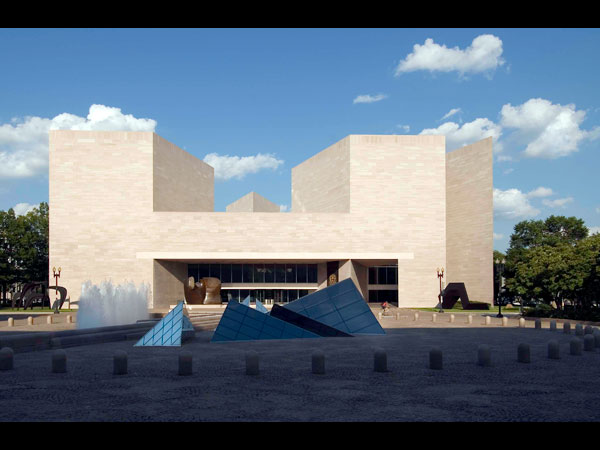

National Gallery of Art, East Building, west facade, 2008. National Gallery of Art, Washington; photograph by Rob Shelley.

National Gallery of Art, East Building, west facade, 2008. National Gallery of Art, Washington; photograph by Rob Shelley.The architect of the new African-American museum was selected through a design competition. By contrast, industrialist Andrew W. Mellon, who paid for—and stocked—the National Gallery of Art, commissioned Pope personally, just as later his son, Paul, with J. Carter Brown, tapped Pei for the East Building. In fact, Pei refuses to enter competitions, for he understands that a great building is the result of an extended process of gestation involving a creative collaboration between architect and client. Still, the popular misperception that architects do their best work under competitive pressure persists. The Smithsonian chose six teams from among 22 submissions and gave them all of two months to solve a challenging set of design problems: a constricted site next to the Washington Monument, a charged subject (slavery, discrimination, race), and the perhaps unanswerable question, What should a museum of African-American history and culture look like?

-

Photograph courtesy Foster + Partners/URS Group Inc.

Photograph courtesy Foster + Partners/URS Group Inc.The winner and five runners-up—models and drawings—were recently on display at the Smithsonian. In some ways, the most compelling design is that of Foster + Partners, which opted for a landscape solution. (The landscape architect is Michel Desvigne.) The oval spiral, which is entered through a sunken entrance court and whose roofs are covered with terraces and gardens, burrows into the ground, reducing the mass—and height—of the building on the small site. The simple shape forms a geometrical bookend to Pei's triangle at the other end of Constitution Avenue. The glass-roofed eye of the oval houses a replica of a slave ship, while the ascending galleries terminate in a glass wall offering a dramatic view of the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. Norman Foster is known for his rational approach to design, and he skillfully resolves many of the planning issues, including a simple relationship to the Washington Monument, although his building is perhaps too inward-looking, like the self-contained Hirshhorn that it slightly resembles.

-

Photograph courtesy Moshe Safdie and Associates Inc.

Photograph courtesy Moshe Safdie and Associates Inc.Moshe Safdie and Associates' scheme is a polygonal building cut through by a top-lit diagonal slot, lined with delicate wood screens that evoke giant basketwork. As in Foster's building, the gently curved atrium opens up to a view of the Washington Monument, which is a device that Safdie used in the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem. Yad Vashem is perhaps the most moving museum of its type built in recent years, but in Washington, Safdie falters. The huge sculptural shapes that frame the view from the atrium are insufficient to enliven what is a rather plain building; moreover, the sculptural forms appear whimsical and arbitrary. It's hard to fathom what they signify: the prow of a ship, a cracked urn, giant bone fragments?

-

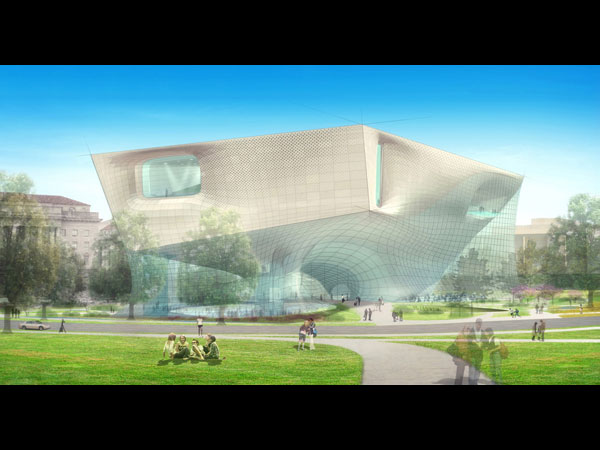

Photograph courtesy Diller Scofidio + Renfro in association with Kling Stubbins.

Photograph courtesy Diller Scofidio + Renfro in association with Kling Stubbins.Architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro allow the public to move under and through their building, an interesting concept for this location, which people approach from all directions. But the architecture is weird. The architects quote W.E.B. Du Bois on the "two warring souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings" of African-Americans, and their building is certainly at war with itself. The solid portion—which appears to be melting—is covered in limestone; the transparent portion—a double-curved, cable-supported glass skin—is draped over the box. This computer-generated architecture looks exciting in drawings, although the model on display at the Smithsonian was crude and gave little assurance that such an eccentric building should—or, indeed, could—be built. Definitely in the pink-flamingo category.

-

Photograph courtesy Moody-Nolan Inc./Antoine Predock Architect PC.

Photograph courtesy Moody-Nolan Inc./Antoine Predock Architect PC.Albuquerque-based Antoine Predock is known for his bold, sculptural designs carried out in an expressive, highly personal manner. In this proposal, he pulls out all the stops; there are exotic materials (mica-schist quartzite, Mpingo wood), dramatic interior spaces, naturalistic forms. It looks as if the building had been pushed up from the ground by some sort of earthquake or eruption. One senses that the architect is trying to uncover an architectural expression for an African-American museum, but in the end it is really more about him than about his subject. I'm not sure whether this confusing building is beautiful or not, and while it might be suitable for certain settings, I am certain that the corner of Constitution Avenue and 15th Street is not one of them.

-

Photograph courtesy Devrouax + Purnell Architects, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners Architects.

Photograph courtesy Devrouax + Purnell Architects, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners Architects.You might think that Pei Cobb Freed & Partners would have had an inside track in the competition—after all, not only Pei's East Building but James Ingo Freed's Holocaust Memorial Museum are a just a stone's throw away. (Pei retired in 1990; Freed died in 2005.) Yet the coy mating of a glass free-form shape with a rectangular, more traditional masonry-clad frame lacks conviction. Twenty years ago, Arthur Erickson tried to combine modern and neoclassical motifs in the Canadian Embassy, and it doesn't work any better for Pei Cobb Freed than it did for him.

-

Ken Rahaim, Smithsonian Institution.

Ken Rahaim, Smithsonian Institution.The lead designer of the winning entry is David Adjaye, an up-and-coming British architect of Ghanaian descent, here teamed with the Freelon Group; New York firm Davis Brody Bond, which is designing the museum at the World Trade Center site; and SmithGroup, a national firm that will oversee construction. At the press conference announcing the winner, Adjaye described his design as "a crown on top of a mound." The metal crown contains the galleries; the limestone-covered mound, or base, houses exhibition spaces as well as a large lobby that is entered from Constitution Avenue (right); and through a wide porch facing the Mall. The roofs will be landscaped terraces. This is the most conservative of the six designs—no curves, no angular planning, no gymnastics.

-

Photograph courtesy Freelon Adjaye Bond/SmithGroup.

Photograph courtesy Freelon Adjaye Bond/SmithGroup.The Freelon Group is one of the largest minority-owned firms in the United States, and Max Bond is considered by many the dean of African-American architects. (Bond passed away while the competition was under way.) The Freelon Adjaye Bond team ranks high on the minority scale, but its members have a much scantier record of distinguished architectural achievement than either Foster or Safdie. I suspect that one of the things that swayed the jury was the simple and effective imagery of the crown. Wrapped in a perforated bronze skin that will reflect different colors during the day, the crown will act as a beacon at night. The memorable form can be interpreted as two baskets, a motif from West African tribal art, a Brancusi sculpture—or an exotic garden ornament. The design manages to appear both primal and modern and, in some ineffable way, seems right for an African-American museum—respectful of the Mall, yet standing slightly apart.