Houses Made in Factories

-

Richard and Su Rogers. CREDIT: Zip-Up Enclosures No. 1 and 2, 1968-71 Model. On behalf of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

Richard and Su Rogers. CREDIT: Zip-Up Enclosures No. 1 and 2, 1968-71 Model. On behalf of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.The subject of the current Museum of Modern Art exhibition "Home Delivery" is historic and contemporary factory-produced housing. The most emblematic object in the show is a model of a prefab house designed in the late 1960s by Richard and Su Rogers. It is emblematic because it is a striking design (a yellow tube of aluminum panels on spindly pink legs), has a trendy name ("Zip-Up Enclosure"), and, while placing second in a competition, was never built. Prefabricated houses have remained an elusive goal for architects, and the MoMA show is a stylish litany of second-place finishers, also-rans, if-onlys, and downright losers. A corner of the exhibit is devoted to a (only slightly rusty) section of the legendary Lustron house, an all-metal 1940s prefab of which 2,500 were built—before its maker declared bankruptcy. Perhaps realizing the somewhat discouraging message of this historical retrospective, Barry Bergdoll, chief curator of architecture and design at the museum, added an arresting fillip: not just photos, models, and drawings of prefabs but also the real thing.

-

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.Immediately next-door to the museum, on a vacant lot that is the site of a future skyscraper being designed by Jean Nouvel, are five full-size model houses commissioned especially for the exhibition. Don't look for Nouvel or Richard Rogers, though. After considering some 500 firms, the museum chose younger, lesser-known architects, and the range of solutions demonstrates both a sense of enthusiasm and a variety of novel prefabrication technologies. Among these are computer design and digital fabrication, in which the architect's computer is directly linked to an automated production machine such as a laser cutter. Both techniques figured in the house by Jeremy Edmiston and Douglas Gauthier (foreground right), a version of a summerhouse they have built in Australia. The rather crudely built structure looks out of place here—or, I suspect, anywhere.

-

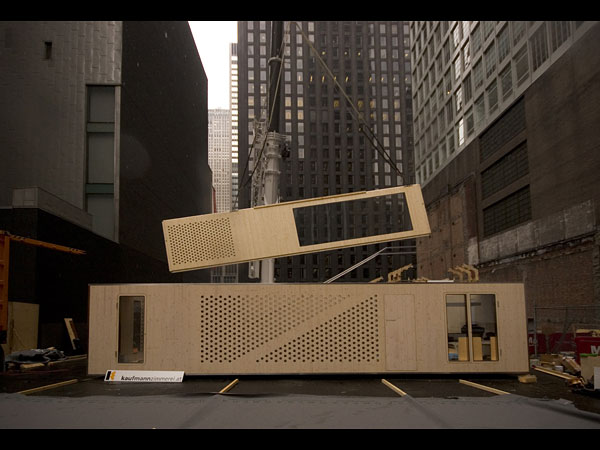

System3, as designed for MoMA's Home Delivery exhibition. Oskar Leo Kaufmann and Albert Rüf. Photograph by Richard Barnes © 2008 the Museum of Modern Art.

System3, as designed for MoMA's Home Delivery exhibition. Oskar Leo Kaufmann and Albert Rüf. Photograph by Richard Barnes © 2008 the Museum of Modern Art.System3 is a more conventional sort of prefab. Designed by Austrian architects Oskar Leo Kauffmann and Albert Rüff, it is assembled out of panels and three-dimensional components that arrive to the building site in a shipping container. Several finished modules are combined or stacked to make a house or can be piled up to create a multistory apartment building. System3 is most people's idea of contemporary prefabrication: It's elegant, stylish, and rather austere.

-

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.The Holy Grail of prefabrication is a house that is inexpensive as well as easy to build. The Instant House, designed by Lawrence Sass and a team of students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, combines these ambitious goals in the service of a lofty ideal: rebuilding New Orleans. The result resembles the Katrina Cottage, a traditional-looking small house developed two years ago as an alternative to FEMA trailers. Although the MIT cottage looks like an old-fashioned shotgun house, it is anything but. The house is built out of plywood sheets whose laser-cut grooves and joints enable the pieces to be connected without nails or screws. A portable laser cutter, controlled by a computer program, is brought to the site and purportedly can transform a stack of plywood into a building "at breakneck speed."

-

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.The Instant House seems like an ingenious and very complicated answer to the wrong question. Why make a house entirely out of exterior-grade plywood, which is an expensive building material? Why go to all that trouble merely to get rid of nails? Why leave all those edge joints exposed to the weather so that they can shrink and swell? The first thing an owner will have to do is cover the jigsaw-puzzlelike surfaces with vinyl siding on the exterior and sheetrock on the inside, which will significantly add to the cost—and the construction time. The laser-cut decorative fretwork on the porch is nice, though.

-

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.Most of the prefabs in the show come under the category of "bright ideas," but the Micro Compact Home has actually been on the market for three years. It is sold as a ski shelter, beach cottage, temporary quarters, or student housing. Designed by London-based Richard Horden, with Haack + Höpfner Architects of Munich and London, the 2.2-ton cube is delivered from a factory in Austria fully furnished; just plug in and play. The interior, which is a cross between a Volkswagen camper and railway sleeping compartment, contains a kitchen, shower, toilet, broadband Internet connection, two fold-down double beds, and two flat-screen televisions. Nothing revolutionary here, but a very nicely designed package.

-

Airstream Sport, 2008 model. Courtesy Airstream Inc.

Airstream Sport, 2008 model. Courtesy Airstream Inc.The Micro Compact Home sells for between €25,000 and €35,000 (roughly $39,000-$55,000). Even taking into account our diminished dollars, that is steep. The vexing thing about architectural prefabs is their price; whatever the promises of mass production and standardization, they always seem to end up costing a lot. But if you do have $30,000 to spare, you'd be better off getting an Airstream Sport. The Airstream trailer, invented in 1936 by Wally Byam—an entrepreneur, not an architect—is not in the MoMA show, but it should be (the museum actually has one in its collection). This remarkably long-lived product, which put aircraft technology on the road, continues to deliver on the promise of the factory-produced home. And you don't need a crane to move it from place to place.

-

House in the Museum Garden, 1949. Courtesy Ezra Stoller. © 2008 Esto. All rights reserved.

House in the Museum Garden, 1949. Courtesy Ezra Stoller. © 2008 Esto. All rights reserved."Home Delivery's" five houses join a long tradition of model homes at the Museum of Modern Art. The first full-scale exhibition house, designed by Marcel Breuer, was built in the Modern's sculpture garden in 1949. Breuer (1902-1981) is probably best remembered for his classic Cesca armchair, a tubular steel and caned seat and back design that is the most popular chair of the early Modern period, but he also designed exceptional houses. His pragmatic take on the International Style combined clean, simple lines with nonindustrial materials such as fieldstone and wood. There is an unself-conscious quality to this comfortable and livable house that is still compelling, 59 years later. (The house is now part of the Rockefeller estate at Pocantico Hills, N.Y.)

-

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.At 1,800 square feet, the house designed by Stephen Kieran and James Timberlake of Philadelphia is the largest of the five. It comes closest to the spirit of the Breuer house, since it's a real home, with bedrooms, bathrooms, closets, a roof terrace, even a carport. But while Breuer was clearly designing for the suburbs, this five-story structure is intended for a small urban lot. The miniskyscraper seems just right for its Midtown location, with the Saarinen-designed CBS Building in the background. (Full disclosure: Kieran and Timberlake are both adjunct professors at the University of Pennsylvania, where I teach.)

-

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.

Courtesy Witold Rybczynski.Kieran and Timberlake prefer the term off-site fabrication to prefabrication, and their building method resembles the 2-by-4 frame of a traditional stick-built house, in the sense that standardized factory-made bits and pieces are assembled on the building site. The big difference is that the off-the-shelf aluminum frame is bolted together and filled in with a variety of screw-on and snap-in components: polypropylene sheet walls, glazing, exterior skin, and a thin-film wrapper with embedded photovoltaic cells (hence the overly cute name, Cellophane House). The house is a combination of three-dimensional modules, panels, and frames. The design, fabrication, and construction are seamlessly integrated, and the various pieces are automatically ordered from the fabricator to suit the design as it is entered into the architect's computer. If there is a Next Big Idea in prefabrication, this may be it.