Save the Mount!

Why Edith Wharton's house is an architectural treasure.

Update, April 24, 2008: Thanks in part to contributions from Slate readers, the Mount was able to get its foreclosure deadline extended from today to May 31. Susan Wissler, acting executive director of the Mount, wrote, "Slate had much to do with the extension. The uptick in web contributions from the day the Slate piece appeared was immediate and significant." Keep up the good work. The official site of the Mount has all the details.

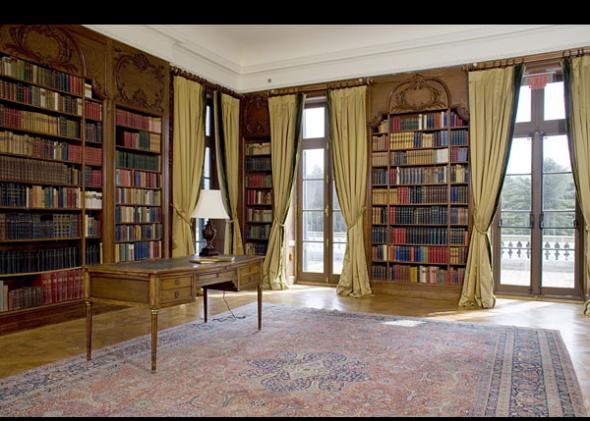

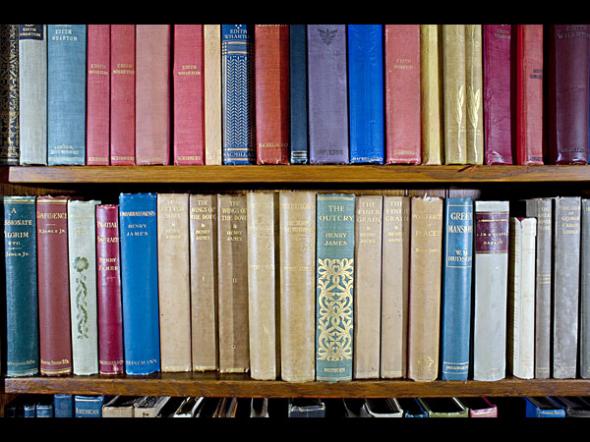

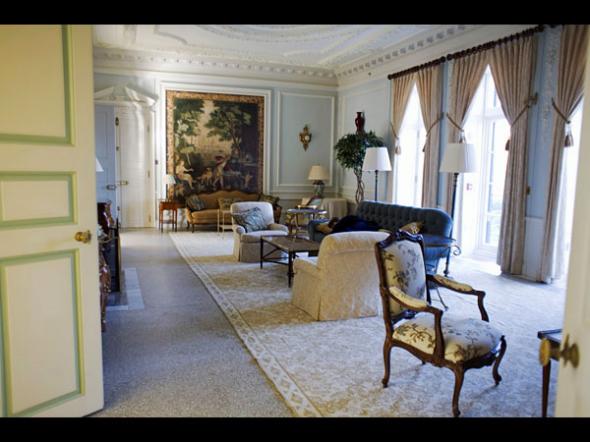

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.

Photograph by Willy Somma.