Cars, Chairs, and Teapots, Oh My!

-

Tatra T87 Saloon Car, © Lloyd Wolf.

Tatra T87 Saloon Car, © Lloyd Wolf.Ernest Flagg was a Beaux-Arts graduate who designed the Singer Building in New York as well as the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. I wonder what he would have thought of his Tuscan atrium at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., being turned into an automobile showroom. The Tatra T87 Saloon is part of the Corcoran's current exhibition, "Modernism: Designing a New World, 1914-39," which runs until July 29. The Czech rear-engine luxury limousine, which was introduced in 1937, seats six and has a huge dorsal fin, though handling was notoriously unstable when the car reached its top speed of 100 mph. The bodywork, designed by Hungarian Paul Jaray, influenced Ferdinand Porsche's Kdf-Wagen, the precursor to the Volkswagen Beetle. The contrast between the streamlined Tatra and its neoclassical surroundings could not be greater—or more dramatically signal the theme of this show: the advent of a radical new age in design.*

*Correction, July 11, 2007: This sentence originally stated that the bodywork of the Tatra T87 also influenced the design of the Chrysler Airflow. It was the predecessor to the Tatra T87, the T77, that influenced the Chrysler Airflow.

-

Marcel Breuer, CREDIT: chair, model B32 © V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Marcel Breuer, CREDIT: chair, model B32 © V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.The idea that Modernism in the arts was a response to a new world is hardly original. And, as we shall see, the Corcoran curators missed an opportunity to relate European Modernism to what was going on in America. Still, it is fun to see so many objects brought together in one place. An entire room is devoted to furniture. Most people will recognize the classic Cesca side chair, also called Chair B32, designed by Marcel Breuer in 1928. Like many chairs of that period, it is still in production. The bent, tubular steel frame resembles an earlier design by Mart Stam, a Dutch architect who was living in Berlin at the time, but its enduring appeal rests on its combination of traditional and modern materials. The beechwood and cane seat and back are pure Breuer. They give the chair its comfort—and slyly undermine the machine aesthetic of the chromed tubing.

-

Alvar Aalto,CREDIT: Paimio chair © V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Alvar Aalto,CREDIT: Paimio chair © V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.Another Modernist who defies easy categorization is Finnish architect Alvar Aalto. His Paimio armchair, for example, designed in 1930, definitely does more with a lot less. Aalto pioneered the technique of bending solid birch and birch plywood. The result was this beautiful armchair, first used in his famous Paimio Sanatorium, a Modernist icon that continues in use as a hospital today. Aalto's humanist version of Modernism has proved more durable than many of the more orthodox designs of what historian Reyner Banham called the First Machine Age, whose products often looked more functional than they really were.

-

Naum Slutzky, teapot © V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Naum Slutzky, teapot © V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.Breuer taught furniture design at the Bauhaus. Thanks to this arts-and-design school, which was founded in Weimar in 1919 and continued (in Dessau and later Berlin) until 1933, Modernism influenced a wide variety of fields: not only furniture, but also photography, art, graphics, textiles, and the design of a variety of domestic objects and appliances. The Corcoran show includes desk lamps, radios, and the Minox miniature camera, whose design today is little changed since 1936. Naum Slutzky, who taught metalwork at the Bauhaus, designed this chromium-plated brass teapot in 1928. (For some reason, Modernist designers were fascinated by teapots.) Slutzky's model is less well-known than Marianne Brandt's silver tea infuser, or Wilhelm Wagenfeld's laboratory-glass teapot, but it has a pleasant shape and, like many Bauhaus products, emphasizes craft rather than factory-production.

-

Mies van der Rohe, CREDIT: Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper, 1921 © 2007 Artists Rights Society, N.Y./VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Digital image © the Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA /Art Resource, N.Y.

Mies van der Rohe, CREDIT: Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper, 1921 © 2007 Artists Rights Society, N.Y./VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Digital image © the Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA /Art Resource, N.Y.The largest contingent in the Modernist vanguard were the architects. It is always difficult to transport architecture to a museum, and although the Corcoran includes photographs and models of buildings, these are less compelling than actual cars, chairs, and teapots. An exception is Mies van der Rohe's 6-foot-tall charcoal sketch, which towers over the viewer and gives a palpable sense of its subject. The 20-story Berlin office building it portrays was designed in 1921 as a competition entry. American skyscrapers, such as Raymond Hood's 1924 American Radiator Building (on New York's Bryant Park), were usually designed as pinnacles or spires, but Mies' glass iceberg exploited transparency. However, by the time that the German architect actually built a tall building—24 years later in Chicago—he had abandoned poetic expressionism and opted for something more straightforward, and more practical.

-

CREDIT: Frankfurt Kitchen © V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

CREDIT: Frankfurt Kitchen © V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.One of the most effective architectural exhibits in the Corcoran show, because it is the real thing, is the so-called Frankfurt Kitchen. This interior was originally in an apartment building in Frankfurt, part of Modernist architect Ernst May's social housing program of the '20s. Architect Grete Lihotzky worked for May and designed this compact work space, which was built in large numbers. The labor-saving plan, which included a complicated system of storage bins (but no refrigerator) was intended to maximize the small space and to reduce the movement of the homemaker.

-

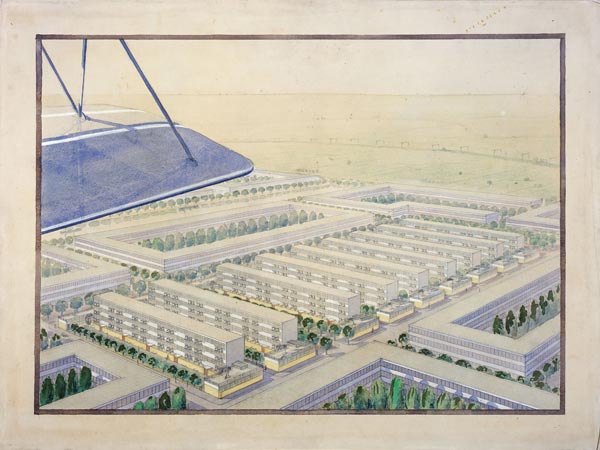

J. J. P. Oud, Design for Blijdorp Municipal Housing, 1931-32. Courtesy Nederlands Architectuur Instituut, Rotterdam.

J. J. P. Oud, Design for Blijdorp Municipal Housing, 1931-32. Courtesy Nederlands Architectuur Instituut, Rotterdam.Modernist architects were preoccupied with mass housing. This development by Dutch architect J.J.P. Oud is a model of the type: standardized, repetitive, and hyperrational in plan (the apartment blocks were lined up to maximize sunlight). It happens to be in Rotterdam, but it could equally well have been in Berlin, Vienna, or Moscow—or (much later) Chicago's South Side. Modernist mass housing projects have been much vilified—and rightly so. They often turned out to be inhospitable, anti-urban, and soulless. This makes Oud's evocative drawing all the more bittersweet. It has the guileless, youthful optimism of all fresh beginnings.

-

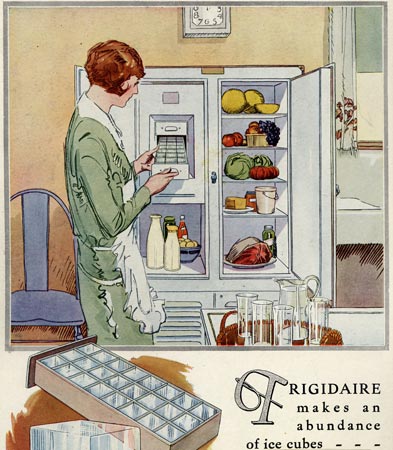

Frigidaire advertisement, 1920s. Courtesy Frigidaire Collection at the Kettering University Archives.

Frigidaire advertisement, 1920s. Courtesy Frigidaire Collection at the Kettering University Archives.The Corcoran show was organized in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. That explains its Eurocentric bias, which gives the unwary visitor the distinct impression that the most advanced industrial societies in the world in the 1920s were Weimar Germany and the Communist Soviet Union. But, of course, they weren't. It was only in the United States that modernity—as opposed to Modernism—was a fact of life. By 1920, nine out of 10 cars in the entire world were Fords. Electrification was widespread. Domestic technology included electric fans and irons, vacuum cleaners and washing machines, as well as central heating. In 1923 there were 20,000 refrigerators in the U.S.; by 1933, 850,000. In the United States, modernity was not an artistic ideology but a marketing phenomenon. American designers were pragmatists. "Design combines good taste, technical knowledge, and common sense," wrote Raymond Loewy, who designed Frigidaire refrigerators, International Harvester tractors, and Lucky Strike cigarette packaging.

-

Richard Neutra, Philip Lovell residence. © Wayne Andrews / Esto.

Richard Neutra, Philip Lovell residence. © Wayne Andrews / Esto.While European architects were making charcoal sketches of skyscrapers, American architects were building the real thing, which pushed construction techniques to the forefront. The European "machines for living," such as Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye (1928), which appears on the jacket of the exhibition catalog, looked "modern," but they were built out of bricks and mortar, plastered over and painted white. On the other hand, a contemporary American house such as Richard Neutra's Lovell House (right) in the Hollywood Hills was really assembled like a machine, its steel skeleton filled with lightweight, prefabricated, industrially produced materials. The architect was Viennese, but his California work shows an edgy, American know-how. Later, Neutra would design Los Angeles' first drive-in church.

-

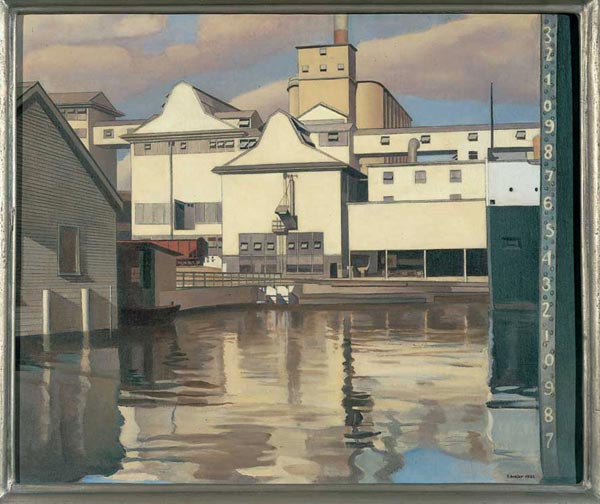

Charles Sheeler, CREDIT: River Rouge Plant, 1932. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Charles Sheeler, CREDIT: River Rouge Plant, 1932. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.European artists and architects were fascinated by Modernism precisely because it was exotic, while in America modernity was simply part of the landscape. The latter sentiment is beautifully conveyed in Charles Sheeler's 1932 painting of the giant Ford automobile plant at River Rouge near Detroit, which is in the Corcoran show. Without the heavy-handed, self-consciously heroic posturing of the European Modernists, Sheeler quietly portrays a new—and as yet unrusty—industrial landscape, with bright sun, puffy clouds, and rippled reflections in the water. This is now our world, he seems to say. So what?