Tiffany the Architect

-

Louis Comfort Tiffany, Tiffany Studios, Wisteria panel (detail), from a frieze for dining room at Laurelton Hall,CREDIT: c. 1910-20. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Louis Comfort Tiffany, Tiffany Studios, Wisteria panel (detail), from a frieze for dining room at Laurelton Hall,CREDIT: c. 1910-20. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.With the possible exceptions of Gustave Stickley and Frank Lloyd Wright, the work of no American designer of domestic interiors is as immediately recognizable—and as popular—as that of Louis Comfort Tiffany. Tiffany (1848–1933) was the son of the founder of the famous luxury-goods emporium, and on his father's death in 1902 he inherited $3 million, a chunk of which he devoted to building a grand country estate on Long Island. The house, Laurelton Hall, burned in 1957. However, several architectural fragments have survived, as well as portions of its decorative fabric and contents, which had been auctioned off some years earlier. This material, including a beautiful Favrile-glass frieze that once adorned the transoms in the dining room, has now been brought together in a major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (through May 20, 2007).

-

Daffodil Terrace, photographed by Joseph Coscia Jr. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Daffodil Terrace, photographed by Joseph Coscia Jr. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.Laurelton Hall, an 84-room mansion, occupied 580 acres overlooking Cold Spring Harbor. The estate encompassed 60 acres of formal gardens, an immense conservatory, a farm, and a private dock for Tiffany's fleet of yachts, as well as its own railroad station. By the exalted standards of the Gilded Age, it was a run-of-the-mill millionaire's spread. Its architecture, however, was entirely atypical. The largest architectural fragment in the Met show is the Daffodil Terrace, an open porch that projected into the garden on the south side of the dining room. Tiffany transformed the capitals of the columns from classical acanthus leaves into bound bunches of daffodils, with dewy petals of annealed glass. This whimsical conceit pays tribute to—and simultaneously undermines—an ancient Greek architectural tradition. The rebuilt porch looks rather stark in a museum gallery, but one must imagine it in full sunlight, filled with cushioned wicker furniture, with a tree growing through the central opening.

-

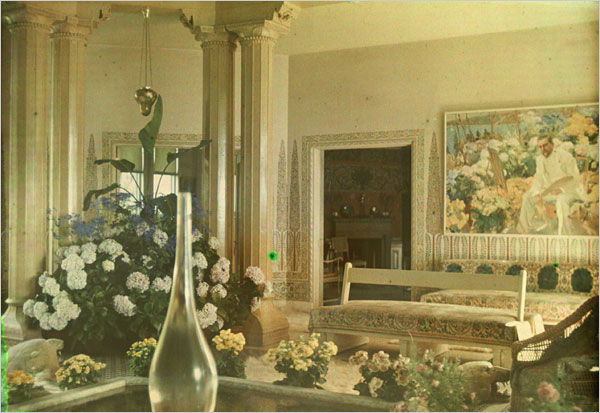

Fountain Court, Laurelton Hall. Image courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Fountain Court, Laurelton Hall. Image courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Metropolitan Museum, New York.Tiffany designed the garden, the house, and everything in it. Like Wright, who was building his Prairie houses at roughly the same time, Tiffany intended Laurelton Hall as an aesthetic challenge to the current practice of designing country houses using historical European styles such as Italian Renaissance and British Georgian. He was no Modernist, however. He simply looked farther afield—to Mogul, Moorish, and Byzantine sources. Tiffany designed his house from the inside out, room by room, giving each a distinctive character. The centerpiece of the plan was an octagonal reception hall, the Fountain Court, shown in an old autochrome slide at right. The three-story space was covered by a translucent blue-purple glass dome, the Hindu-like columns were marble, and the stenciled cypress-tree patterns on the walls were adapted from Istanbul's Topkapi Palace. The overall effect must have been distinctly exotic, an impression that would have been heightened by Tiffany's collection of Chinese and Japanese artifacts, which are also featured in the exhibition.

-

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, Louis Comfort Tiffany, 1911. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, Louis Comfort Tiffany, 1911. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.The crowd-pleasing Met show presents Tiffany as an artiste, but he was also a successful entrepreneur (his Tiffany Studios factory employed 300 workers), a wealthy bon vivant and thrower of legendary parties, an enthusiastic gardener, and a family man (he had eight children). His extravagance is reflected in Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida's over-the-top portrait, which originally hung in the Fountain Court. Indeed, Tiffany's immoderation is a big part of the appeal of his sinuous, stylized natural forms and flamboyant colors. His designs are distinctly excessive (the daffodil capitals at Laurelton Hall alone cost more than $100,000 in modern dollars) but also quite wonderful, in an otherworldly sort of way.

-

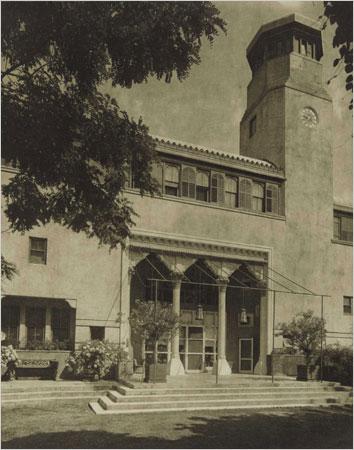

View of loggia, Laurelton Hall. From Charles de Kay, CREDIT: The Art Work of Louis C. Tiffany (1914). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.

View of loggia, Laurelton Hall. From Charles de Kay, CREDIT: The Art Work of Louis C. Tiffany (1914). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.A single Tiffany vase, a leaded-glass lamp, or a Favrile glass panel is a compelling presence. But how did his taste translate into an entire building? Although the Metropolitan Museum has subtitled the exhibition "An Artist's Country Estate," the curators have made little effort to portray or explain the architecture of this unusual house. A reconstruction of the vanished structure in either model or digital form would have helped the visitor to understand Tiffany's creation. And an explanation is needed, for what, exactly, do all the beautiful bits and pieces add up to? An artistic achievement, or a rich man's folly? On the basis of the scant evidence, it's hard to decide. The surviving photographs show an oddly lumpish building, whose makeshift composition reveals the drawback to Tiffany's eccentric design method. The beautiful pieces don't quite come together: The artist-as-decorator is more convincing than the artist-as-architect.

-

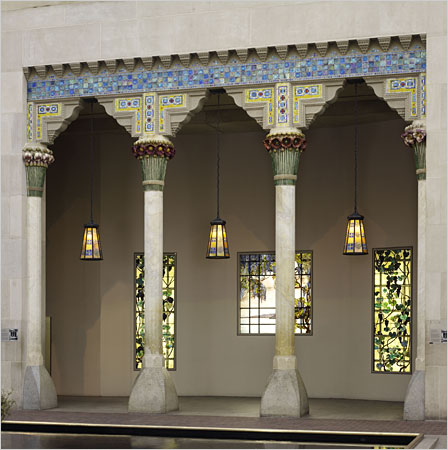

Louis Comfort Tiffany, loggia, Laurelton hall, c. 1905. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Louis Comfort Tiffany, loggia, Laurelton hall, c. 1905. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum, New York.The most impressive surviving fragment of Laurelton Hall, a four-columned portico, is not in the show but nearby in the American Wing. The portico, which led from the garden to a loggia outside the Fountain Court, was modeled on one in the Mogul Red Fort in New Delhi. The capitals are Tiffany's own addition, however, and represent four different flower species: lotus, peony, poppy, and magnolia. Seeing the portico in full natural light, and in a large space, gives a different impression of Tiffany's architectural intentions than do the exhibits in the show: less precious, tougher, but also more strangely foreign. Surely not an "American" architecture, whatever its maker's claim.