The Memorial of Washington, D.C.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.What makes a good memorial? Since memorials have only one function—to commemorate people or events for posterity—a simple answer might be "A good memorial is one that endures." But even a durable memorial can become obsolete. Many consider the innumerable statues of Civil War generals on plinths that dot our nation's capital to be out of date. We've forgotten the men's names and their achievements; the heroic figures no longer move us. These large chunks of bronze have become invisible. Even old-time Washingtonians look blank when I ask them about the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial (at right). When it was dedicated in 1922, the group of statues, which occupy a 252-foot-wide plaza at the base of Capitol Hill, was the most expensive art project in American history. Grant is one of only four presidents to be given pride of place on the Mall. There he sits, on his favorite horse, "Cincinnati," gazing at the distant Lincoln Memorial, imperturbable, rock-steady, the wind at his back—forgotten.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.Yet the Grant Memorial is good. The sculptor, Henry Merwin Shrady, labored 20 years—most of his professional life—on the project and died only weeks before its dedication. The composition is simplicity itself. The mounted general is raised on a tall pedestal decorated with bas-reliefs of marching troops. At the base, four reclining lions symbolize victory. There are no inscriptions, no dates, no battle names, just a single word: "GRANT." Flanking the main figure, which is one of the largest equestrian bronzes in the world, are two groups representing charging cavalrymen, and an artillery unit hauling a caisson and a gun (at right). While Grant exemplifies taciturn calm, they are all explosive action. Flying mud churned by the horses' hooves, the straining soldiers urging their mounts forward, hurtling recklessly ahead. The effect is cinematic; imagine Sam Peckinpah in bronze.

-

Photographs by Witold Rybczynski.

Photographs by Witold Rybczynski.The grandest—and oldest—memorial on the National Mall is the Washington Monument. It commemorates another general-president, but it does not do so with an equestrian statue, as Pierre-Charles L'Enfant indicated in his original city plan, but with a giant obelisk. The tapered form is an ancient type of memorial, like the column, the triumphal arch, or the stele. This mute sentinel does not include Washington's name, and there is no iconography explicitly referring to him. The monument is huge—555 feet high. When the architect Robert Mills designed it in 1845, the tallest obelisk in the world, at St. John Lateran in Rome, was only 106 feet high. The Washington Monument is both excessive in scale and very moving. It seems to stand not so much for the man—though he was exceptionally tall, too—but for the revolution that he led, and for its lofty ideals.

-

Photograph by Andy Bowers.

Photograph by Andy Bowers.The power of a memorial lies not only in what it is but also in where it is. The Washington Monument is at the symbolic center of the capital, hence at the center of the nation itself. The Lincoln Memorial, which terminates the west end of the Mall, likewise gains importance from location. It was designed by Henry Bacon in the form of a Greek temple, but with a top-lit cella, or sanctuary, and a broad opening to the exterior. There are other nontraditional features. The building is entered through its long facade, and it sits on a mound, reached by a tall flight of steps. The custom in contemporary memorial design is to place everything at ground level, as if that were more democratic. But there is nothing like climbing up to produce a sense of having arrived at somewhere important.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.A good memorial does not need to be a great work of art: One thinks of the rousing Marine Corps War Memorial, which is an overscaled copy of a celebrated news photograph of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima, or of the endearing Central Park monument to Balto, the heroic Alaska sled dog. But Daniel Chester French's seated Lincoln is very good, indeed. Placing the image of a president inside a temple risked hollow hagiography, but French and Henry Bacon pull it off. Experimenting with full-size plaster mock-ups in the finished building, they produced a perfect spatial relationship between the marble statue and its architectural surroundings; the 19-foot-tall figure is neither too small nor too big. French depicts Lincoln as gaunt and somewhat tired, which makes the seated giant appear all the more human.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The Jefferson Memorial was dedicated two decades later, in 1943, and it, too, is in the form of an ancient temple containing a large statue. Franklin Delano Roosevelt commissioned the memorial and ensured its prominent location on the cross-axis of the Mall. The architect, John Russell Pope, conceived it as an open colonnade, but he died before construction began. An earlier design of his, based on the Pantheon in Rome, was built instead. It was greatly vilified by modernist critics, for by then the International Style was all the rage, and Ionic columns seemed old-fashioned, if not downright retrograde. I don't mind the Classical design—after all, Jefferson was an admirer of Roman architecture. But while the marble temple looks well enough when seen across the Tidal Basin, close up it appears overdone and slightly pretentious.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The statue of Jefferson inside the temple is by Rudolph Evans. Unfortunately, Evans was no Daniel Chester French, and his sculpture does little more than offer up the popular image of a wise statesman. There is not a hint of Jefferson's intellectual restlessness, his far-ranging interests, or of his mercurial energy. He gazes benevolently across the Basin to the White House. (Curiously, the White House's architectural design was selected in a competition in which Jefferson was a runner-up.) The orientation is doubly odd for a man who did not greatly value his service as president and famously penned his own epitaph: "Author of the Declaration of American Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom, and Father of the University of Virginia."

-

Photograph by Andy Bowers.

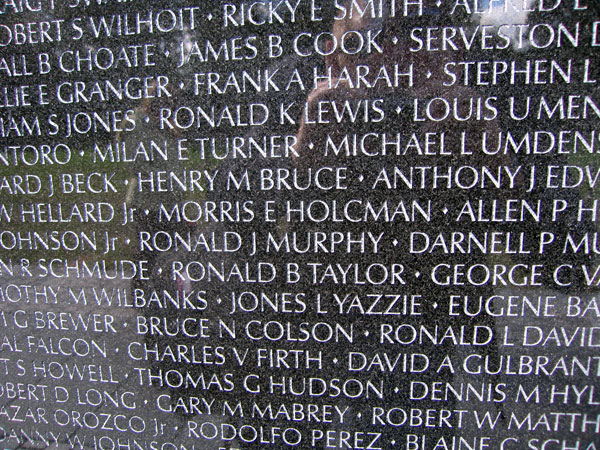

Photograph by Andy Bowers.Lewis Mumford once said, "If it is a monument it is not modern, and if it is modern, it cannot be a monument." But that was before the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. It's the first memorial on the Mall that was conceived (1980-84) in an entirely modern style, without figural sculpture or references to antiquity. Its popular success—if that's the right word—spurred an interest in building memorials. The result has been acres of walls with words on them, as if that (and abstraction) were the secrets of Maya Lin's achievement. But the key to her exquisite design is something else. Like all good memorials, this one functions at different scales, as a large-scale earthwork, and as an intimate experience of loss: It invites you to bend closely to read the names. And while it is resolutely minimalist—as minimalist as the Washington Memorial—it is not abstract. The 58,000 names engraved on shiny black granite make it a giant headstone, while the descending path is a clear reference to the underworld, reinforcing the theme of death.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The Vietnam Veterans Memorial has the advantage of compression: two walls, a path, columns of names. Another modern monument, the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, which was dedicated in 1997, is anything but concise. Designed by the landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, it is a sprawling 7½-acre garden. Massive granite walls enclose four distinct areas—one for each of FDR's terms. These areas are called "outdoor galleries," and artworks evoke the Depression, the New Deal, and World War II. We encounter Eleanor, as well as the president in a wheelchair. The walls are inscribed with FDR quotations. It is all, finally, too much. Despite its thoughtful design, and the intricate fountains that are a leitmotif of the garden, the memorial sinks under the weight of so much information, more like an exhibition than a monument.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.Contemporary memorials are bedeviled by the storytelling impulse, as if their makers had seen too many Ken Burns documentaries. The Korean War Veterans Memorial is a case in point. There are 19 larger-than-life sculptures of servicemen on patrol; there is a Pool of Remembrance honoring the dead, wounded, missing, and POWs; there are the names of the other nations that participated in the UN action; and there is a granite wall with etched images of veterans. Unlike the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the busy Korean War Veterans Memorial, which was dedicated in 1995, looks as if it were designed by a committee (one group of architects won the competition, and a second revamped the design). The other problem with this, and many similar modern memorials, is that they assume an educational rather than merely a commemorative role. We are not only asked to remember, but we are also told what and how to remember.

-

Photograph by Andy Bowers.

Photograph by Andy Bowers.When the design of the World War II Memorial was unveiled, there was opposition to its location—situated between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial—and criticism of its neoclassical design. The former objection, it seems to me, has proved baseless; like the Jefferson Memorial, the World War II memorial is well-integrated into the overall composition of the Mall, and it has already become a successful and lively gathering place. The detailed design of the memorial, by Friedrich St. Florian, is less-accomplished. The chief feature is a colonnade of pylons, or pillars, representing the individual states and territories that took part in the conflict, though the significance of this symbolism is unclear. The division of the memorial into two parts, representing the Atlantic and Pacific theaters of the war, likewise seems fortuitous rather than meaningful. As at the FDR Memorial, there is a profusion of water. Fountains and cascades are traditionally used to create a festive and celebratory atmosphere, and their presence in a memorial to the fallen is distinctly odd.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The World War II Memorial might have been successful had it been satisfied to be merely a public place, an American version of Trafalgar Square, say. But the storytelling impulse surfaces here as well. The memorial is dotted with uplifting quotations by military and civilian leaders, names of battles, and gold stars representing the dead. The communication of information is handled best in a series of bronze bas-reliefs, by sculptor Raymond Kaskey, that portray aspects of the war, at home and on the battlefield. They resemble movie stills and, thankfully, are bereft of captions. One of them shows American and Russian soldiers meeting and shaking hands at the Elbe (at right). Apart from a vague Truman quote that refers to "nations that fought by our side," it is the only reference to the fact that the war was won with allies.

-

Photograph by Andy Bowers.

Photograph by Andy Bowers.Near the World War II Memorial is a small monument commemorating the citizens of the District of Columbia who served in World War I. Hidden in the trees, it is not easy to find. The work of an unknown architect, Frederick H. Booke, the little structure is nothing like its neighbor. At first glance, the circular marble temple looks like a miniature version of the Jefferson Memorial, but it's actually a bandstand. It was designed to accommodate the entire Marine Band, which played there, under the direction of John Philip Sousa, when the memorial was dedicated in 1931. The 500-odd names of the dead are inscribed on the base. (This happens to be the first place on the Mall where women and African-Americans are honored side by side with white males.) Though, sadly, no longer used for musical performances, the memorial is an appropriately modest, compact, and wonderfully cheerful commemoration of personal sacrifice. It is also a reminder of what a good memorial shouldn't be. It doesn't pontificate. It is neither therapeutic, nor didactic. It simply bears witness—forever.