The Aesthetics of Urban Renewal

-

Photograph ofCREDIT: Emerald Necklace, Boston, © Phil Schermeister/Corbis.

Photograph ofCREDIT: Emerald Necklace, Boston, © Phil Schermeister/Corbis.A little historical perspective is required to appreciate the import of the Museum of Modern Art's stimulating new exhibition "Groundswell: Constructing the Contemporary Landscape." A century ago, if you were building a city park system, a college campus, a world's fair, a suburban community, or a new town, the first person you consulted was a landscape architect. Thanks to Frederick Law Olmsted—who built all of the above and virtually invented the discipline—landscape architects were the pre-eminent land planners of the day. Olmsted's so-called Emerald Necklace in Boston, for example, is a combination of park, parkway, and urban engineering that winds its way through several neighborhoods. That was the American city: a commercial free-for-all, given a human face by Arcadian stretches of parks, boulevards, avenues, and residential Elm streets.

-

Photograph of the demolition of Pruitt-Igoe public housing, St. Louis, © Bettmann/Corbis.

Photograph of the demolition of Pruitt-Igoe public housing, St. Louis, © Bettmann/Corbis.During the post-World War II period, landscape architecture's pre-eminence in urbanism was challenged by the new "scientific" profession of city planning. Riding the coattails of the growing popular faith in technology and progress, planners took control, relegating landscape architects to the sidelines. But during the '60s and '70s, the planners stumbled—badly. Their formulations turned out to be misguided and resulted in such debacles as urban freeways, public housing projects, and urban renewal. The planning profession never recovered from these failures and retreated to the bureaucratic thickets of zoning legislation, environmental impact studies, and community participation. That left an opening for landscape architects to take a leading role in shaping cities once more.

-

Photograph of Crissy Field,CREDIT: San Francisco, courtesy of Chamois Moon/Robert Campbell.

Photograph of Crissy Field,CREDIT: San Francisco, courtesy of Chamois Moon/Robert Campbell.And they did: Landscape architecture is back. The MoMA exhibit (which runs from Feb. 25 to May 16) consists of 23 landscape-design projects that, in the words of curator Peter Reed, "reclaim and transform urban spaces—many derelict and in need of rehabilitation—into public parks and gardens." A typical example is Crissy Field, at the northern edge of Presidio National Park on San Francisco Bay (at right). The 100-acre site was previously a U.S. Army airstrip, which Hargreaves Associates has made into an urban park. The park includes a re-created tidal wetlands, a bayside promenade for joggers and bicyclists, a picnic spot, a restored beach, and an area for windsurfers. The result is an attractive combination of the natural, the naturalistic, and the man-made—like an Olmsted park, but greatly simplified and geared to today's active public.

-

Photograph ofCREDIT: Duisberg-Nord Landscape Park, Germany, courtesy of Atelier 17/Christa Panick.

Photograph ofCREDIT: Duisberg-Nord Landscape Park, Germany, courtesy of Atelier 17/Christa Panick.At Crissy Field, the flat area of the original grass landing strip is still apparent; the new does not obliterate the old. Another landscape park that spectacularly makes use of its history is Duisburg-Nord Landscape Park in the Ruhr region of Germany. The 570-acre site, larger than Brooklyn's Prospect Park, is a disused steelworks. Instead of demolishing the industrial plant, the landscape architect, Peter Latz, retained the mill buildings, gas tanks, coke bunkers, and traces of railroad track and made them part of the park. The juxtapositions are both weird and wonderful: an orchard of cherry trees next to a blast furnace (at right); a salvia garden surrounding a ruined chimney; the walls of an ore bunker adapted for recreational rock climbing. Sewage channels have been cleaned up and made into canals, and retention ponds planted with floating water lilies. Footpaths and bridges traverse and penetrate the old structures. The slag heaps sprout wildflowers.

-

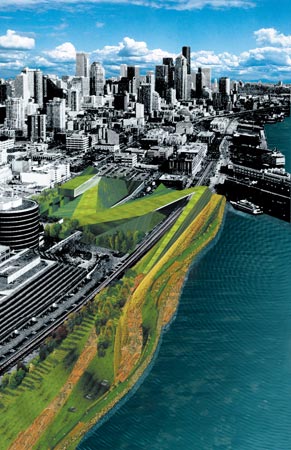

Photograph ofCREDIT: Olympic Sculpture Park Seattle Art Museum, courtesy of Weiss/Manfredi Architects.

Photograph ofCREDIT: Olympic Sculpture Park Seattle Art Museum, courtesy of Weiss/Manfredi Architects.The MoMA show is not really about remediation—despite curator Peter Reed's description—or, at least, it is not only about that. It demonstrates the renewed vigor of landscape design here and abroad. Olympic Sculpture Park (at right), by Weiss/Manfredi, for example, happens to be on the site of a former fuel storage and transfer station in Seattle, but the project (which is under construction) is really about establishing a connection between downtown and Elliott Bay, 40 feet below. Since the park crosses a railroad as well as a four-lane street, it starts as engineering but finishes as a beach along a restored shoreline. Like many contemporary landscape designs, the park incorporates architectural forms, in this case stylish zigzags, but combines them with nature. While Olympic Park fulfills much the same function as Riverside Park in New York City, it does so in an edgy, almost sculptural way.

-

Photograph of the Bordeaux Botanical Garden courtesy of Mosbach Paysagistes/Catherine Mosbach.

Photograph of the Bordeaux Botanical Garden courtesy of Mosbach Paysagistes/Catherine Mosbach.It is the nature of art exhibitions that they are rarely critical. "Groundswell," which is relentlessly upbeat about every project displayed, is no exception. The only implied criticism is of those landscape architects who did not make the cut. Two glaring American omissions are Michael Van Valkenburgh, the designer of Brooklyn Bridge Park, a reclaimed landscape if there ever was one, and Laurie Olin, whose restoration of a Brancusi ensemble in Romania also deserved to be in the show. Nor does "Groundswell" comment on the different and sometimes conflicting tendencies that the exhibits collectively reveal. One is the opposition between landscapes and gardens. The latter have a finer scale and a softer sensibility, as shown by Kathryn Gustafson's heart-wrenching public garden in a bombed-out neighborhood of Beirut. Catherine Mosbach's botanical garden (at right), in a converted industrial neighborhood in Bordeaux, is a research facility, but it may just be the most beautiful landscape in the show.

-

Photograph of Keyaki Plaza, Saitama, Japan, courtesy of Hiroshi Tanaka.

Photograph of Keyaki Plaza, Saitama, Japan, courtesy of Hiroshi Tanaka.A second tension in the MoMA show is between landscape-as-landscape and landscape-as-architecture. The latter, usually designed by architects, tends to be driven by the current trendiness of computer-generated forms—usually extremely complicated ones. This fashionable approach turns out to be constraining, so that several European parks are almost interchangeable in their aesthetic impact. What saves them is that as long as there is greensward to sit on, trees to lie under, and water to wade in, people can enjoy themselves despite the contrived geometry. The same cannot be said of minimalist landscapes. Keyaki Plaza in Saitama, Japan (at right), designed by Peter Walker and Yoji Sasaki, is a rooftop garden that consists of about 200 trees arranged on a grid on what landscape architects call "hardscape." It looks cheerless and monotonous and does not bode well for a comparable design that Walker has proposed for the World Trade Center memorial.

-

Photograph of Invalidenpark, Berlin, Germany, courtesy of Christophe Girot.

Photograph of Invalidenpark, Berlin, Germany, courtesy of Christophe Girot.The third competing aesthetic on view at MoMA is landscape-as-art—a tendency represented in the show by Martha Schwartz's Exchange Square, a pedestrian plaza in Manchester's central shopping district. There are several allegorical features: a water channel with steppingstones that traces the line of Hanging Ditch, an ancient watercourse; grids representing the old and new parts of the city; and benches in the shape of flatcars on illuminated "tracks" that recall the city's industrial past. The effect is Disneyish, in an intellectual sort of way. Ken Smith's roof garden at MoMA can be seen only by the occupants of the surrounding high-rise buildings. The "landscape," which resembles camouflage, is entirely made out of synthetic materials. It's hard to know what to make of it. Invalidenpark, in central Berlin (at right), uses real grass and trees, but Christophe Girot's highly refined design manages to appear artificial, since the park's entire surface is tilted by 1 degree, creating odd junctions where the park meets the surrounding level streets.

-

Photograph of Fresh Kills Lifescape, Staten Island, N.Y., courtesy of Field Operations.

Photograph of Fresh Kills Lifescape, Staten Island, N.Y., courtesy of Field Operations.Since nature does not stand still, man-made landscapes are distinguished from buildings and artworks by the dimension of time, and taking the long view is what landscape architecture can contribute to urbanism. In two impressive industrial remediation projects, one in London's Greenwich Peninsula and the other in Bordeaux, Michel Desvigne shows a plan that extends over intervals of 10, 25, and 50 years. Another project that takes the long view is the Fresh Kills Lifescape, a conversion of the Staten Island landfill to parkland (at right). Instead of a conventional master plan, James Corner of Field Operations has designed a strategy for the next 30 years. Not simply phasing-in an extremely large (2,200 acres) site, it is a dynamic approach related to hydraulic systems, progressive planting, and soil remediation. This is landscape seen not as artifact or as artwork, but as process. Incidentally, Corner's earthwork monument, on the site of the World Trade Center debris, may turn out to be the 9/11 memorial that New Yorkers are waiting for.

-

Photograph of Ground Zero by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

Photograph of Ground Zero by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.The cruel irony of "Groundswell," although the MoMA curators don't mention it, is that only a few miles away is perhaps the best-known degraded urban landscape in the world: the WTC site. If ever there was a place where a long view was required, this is it. Instead, although landscape architects took part in the 2002 competition, decisions about the site were dominated by architects who, encouraged by the public, focused on creating viscerally dramatic forms. Now, as Daniel Libeskind's project unravels, while the gaping excavation remains vacant, the unsuitability of this static approach is evident. The difficult and slow reality of reconstructing such a complex site demands precisely a 50-year plan. A landscape approach to rebuilding would have recognized that something was needed immediately, that whatever this was, it might not be there forever, and that a "plan" should accommodate psychic remediation as well as physical rebuilding. "Groundswell" is three years too late.