What Do Where the Wild Things Are and Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address” Have in Common?

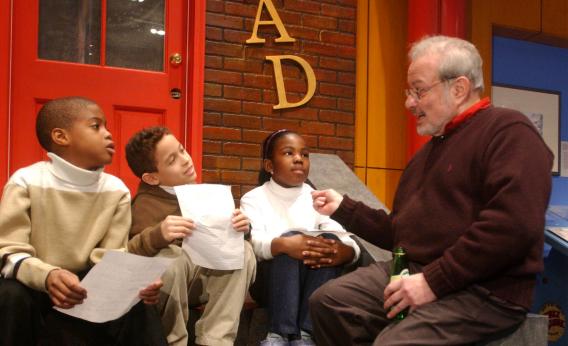

Photograph by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Also in Slate, see Emily Bazelon’s tribute to Maurice Sendak’s particular type of genius. Katie Roiphe admires how Sendak understood that children need to be terrified.

I don’t write for children. I write. And someone says, that’s for children.

When Yeats died, Auden wrote that his poetry “survives/ In the valley of its making.”* That’s what I feel about Maurice Sendak; his words and drawing survive in a valley of their own making, and I am sometimes lucky enough to get invited there. You feel that if Sendak visited your house for a while all the chairs would start developing their own (quiet, amicable but distinct) rules about where they would sit in the kitchen. And that maybe your dog and cat and 4-year-old would have organized a small club that met out in the backyard and had its own flag and its own cosmological constant.

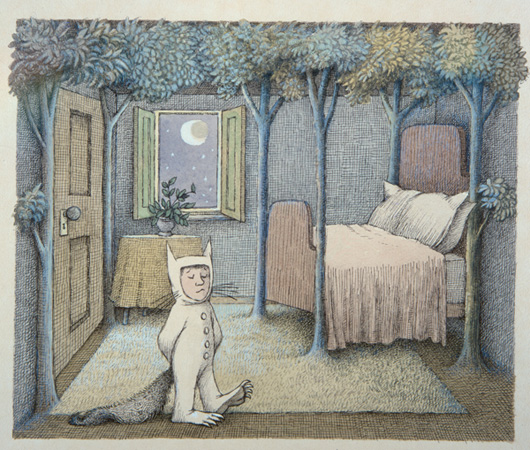

Every time you stumble on a new Sendak book, you find the world getting remade according to some completely brilliant but unparaphrasable set of rules. Not only in Where the Wild Things Are, In the Night Kitchen, and Outside Over There, but even in the books that are not so well read anymore. The sweet savagery of the griffin in the The Griffin and the Minor Canon has been with me almost 40 years now. (How can that book be out of print?) It makes perfect sense to me that Sendak said his gods were Herman Melville, Emily Dickinson, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: crazed worldmakers all.

Sure, you could do a plausible genealogy of Sendak. His ancestors might include The Wind in the Willows and Narnia (aren’t the fussy badgers and neurotic horses so much more appealing than Lewis’ human beings?). And you could point out some family resemblances to the amazing William Steig, whose mice and whales (Amos and Boris, Abel’s Island) are moving around in a world that is not quite our own, but that has its own perfectly clear rules for doing business.

Still, Sendak is wilder at heart than his peers (his raunchy illustrations for Melville’s Pierre and the grim beauty of the pictures he drew for Randall Jarrell’s The Bat Poet are proof of that). And yet his impossible worlds never tip into the antic Dada chaos that makes Dr. Seuss zany—or succumb to the nudge-nudge wink-wink steampunk Victorianness of Edward Gorey and Lemony Snicket.

Johan Huzinga proposed in Homo Ludens that at heart humans are serious players. What makes us human, according to Huizinga, is the capacity to dream up spaces where we can be creative without falling out of bounds. True creativity consists of pushing at the very edges of the space we’ve set up—like a football player tiptoeing down the sidelines to the end zone. Sendak’s books are rule-bound in just that way. And, in the way that the best books always do, Sendak’s stories somehow make their readers do the most exciting sideline tiptoeing themselves.

It’s in the spirit of expressing my awe at Sendak’s worldmaking, finally, that I risk a possibly heretical comparison: What do Where the Wild Things Are and Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address” have in common? Both offered a new way to make sense of the same old world that we’ve always shared with one another. And both took only 10 sentences to do it.

*Correction, April 8, 2012: The blog post originally misquoted Auden, leaving out a word (“the”) that did belong and adding a word (“own”) that didn’t.