This Building Is the Biggest Architectural Movie Star in Los Angeles

Courtesy of Avery Trufelman

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about the Bradbury Building in Los Angeles—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

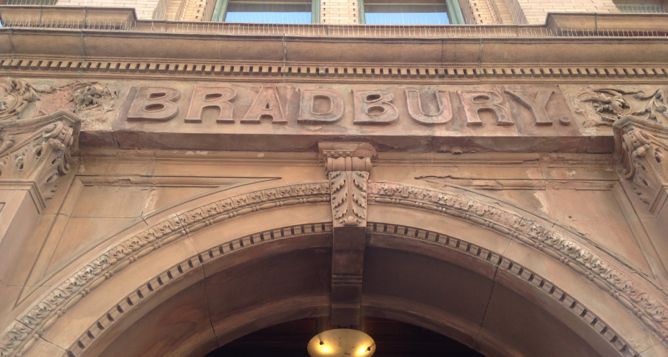

So many classic movies have been made in downtown Los Angeles—even though many take place somewhere else. L.A. has played almost every city in the world, thanks to its diverse landscape and architectural variety, but particular buildings just keep coming back on screen again and again. The Bradbury Building, for instance, is arguably the biggest architectural movie star in all of Los Angeles.

The Bradbury made its first on-screen appearance in 1942, in the movie China Girl, when it played a Burmese hotel. It played a London military hospital in White Cliffs of Dover in 1944. It was the background in the film noir thriller DOA in 1950. In the 1969 movie Marlowe, Bruce Lee steps into an office of the Bradbury and kicks all the furniture apart.

The building played an office again in the final scene of 500 Days of Summer. It was a movie studio in The Artist. And it was a chocolate factory in a recent commercial for Twix.

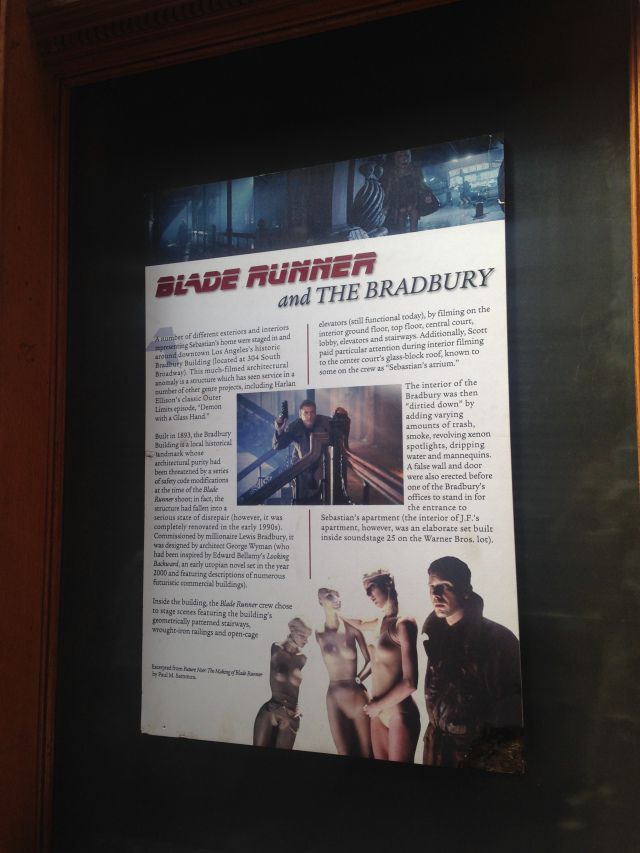

But the Bradbury’s most famous role of all was as the toymaker’s house in the 1982 movie Blade Runner. There’s even a plaque in the lobby about it. In Blade Runner, the Bradbury is a dark, moody ruin—which seems like some real Hollywood magic when you see what the building actually looks like.

Courtesy of Avery Trufelman

From the outside, the Bradbury in downtown L.A. just looks like a brick office building at the corner of 3rd and Broadway. It seems unremarkable, but the magic happens when you step inside. The Bradbury is basically a tall, narrow courtyard, walled in with terra cotta, covered with a glass ceiling, and flanked with two clanking hydraulic-powered elevators. Human conductors still operate them.

Courtesy of Avery Trufelman

There’s a reason the Bradbury is in so many films. Aside from being beautiful, it’s also practical. The balconies allow crews to shoot from many different angles and create a range of different moods for various genres. The Bradbury’s ceiling height can accommodate all the lights and the camera equipment. Also, the Bradbury is located near a parking lot (for all the vans and trailers), as well as places downtown where a film crew can go get lunch.

Courtesy of Avery Trufelman

The Bradbury opened in 1893, long before movies ever came to L.A. For the record, it’s not named after sci-fi novelist Ray Bradbury, but for Lewis Bradbury—a gold-mining millionaire who decided he wanted to make a building with his name on it. In 1892, Bradbury commissioned Sumner Hunt, a famous architect, to design his building.

As the story goes, Bradbury didn’t like any of the plans that Hunt showed him, so he pulled aside George Wyman, one of Hunt's young draftsmen, and asked him to build his very important half-million-dollar office building. Wyman had no professional training as an architect. Not only was he totally unqualified, but he also didn’t want to be seen taking business away from his boss.

But it was an incredible opportunity, so Wyman undertook the then-common practice of attempting to contact a deceased relative for advice on whether to take on the challenge. Wyman attempted to contact his dead brother, Mark, using a planchette, a precursor to a Ouija board that wrote out sentences with a pencil when you rested your hands on it. When Wyman consulted the board, it spelled out in a childlike script: “Take Bradbury … you will be … ” before trailing off into an indecipherable scribble. Read upside down, it said: successful. That was a clear enough message for Wyman, so he said yes.

Courtesy of Avery Trufelman

The design of the Bradbury was directly inspired by a novel called Looking Backwards by Edward Bellamy. Published in 1888, the book takes place in the year 2000. Wyman was inspired by one passage in particular:

It was the first interior of a twentieth-century public building that I had ever beheld, and the spectacle naturally impressed me deeply. I was in a vast hall full of light, received not alone from the windows on all sides, but from the dome, the point of which was a hundred feet above. … The walls and ceiling were frescoed in mellow tints, calculated to soften without absorbing the light which flooded the interior.

The building carries out this 20th-century vision. Even though the Bradbury is quite old (by California standards), it feels modern.

Courtesy of Avery Trufelman

However, aside from the occasional film shoot, the building has spent much of its life totally ignored. When Ridley Scott shot Blade Runner in the central atrium, it actually wasn’t too hard to make the Bradbury look so shabby. The building was in dusty disrepair until developer Ira Yellin bought the property in 1989 and restored it.

Yellin spearheaded L.A.’s downtown revival by restoring old historic buildings and turning them into housing and commercial spaces. The Bradbury was one of the projects he took on, and he asked if the city of Los Angeles could find a steady tenant for the Bradbury. Today, most of the office space in the Bradbury belongs to the internal affairs division of the Los Angeles Police Department.

Courtesy of Avery Trufelman

The police don’t mind the filming, generally, but movies don’t shoot in the Bradbury as frequently as they once did. Generally, filming is not as welcome downtown now that people live and work there. These days, film crews can’t blow up cars in the street or have 300 zombies stampede down Broadway in the middle of the workday. In this way, the downtown revival is a part of why filming is leaving Los Angeles.

Movie makers are now flocking to cities in the South, Midwest, and Canada, which offer major incentives to encourage filming. These tax breaks can save producers millions of dollars, and cities like Atlanta are also developing state-of-the-art studios and attracting good production talent.

Still, there are elements of Los Angeles that cannot be replaced or replicated, even on the finest sound stage. Like the experience of entering the Bradbury Building. It’s a place so unique, so remarkable that after it was built, the draftsman George Wyman decided to take some classes and actually become an architect.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.