The Strange, Spooky History of the Ouija Board

Courtesy of Dave Winer/Flickr

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at The Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about the Ouija board—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

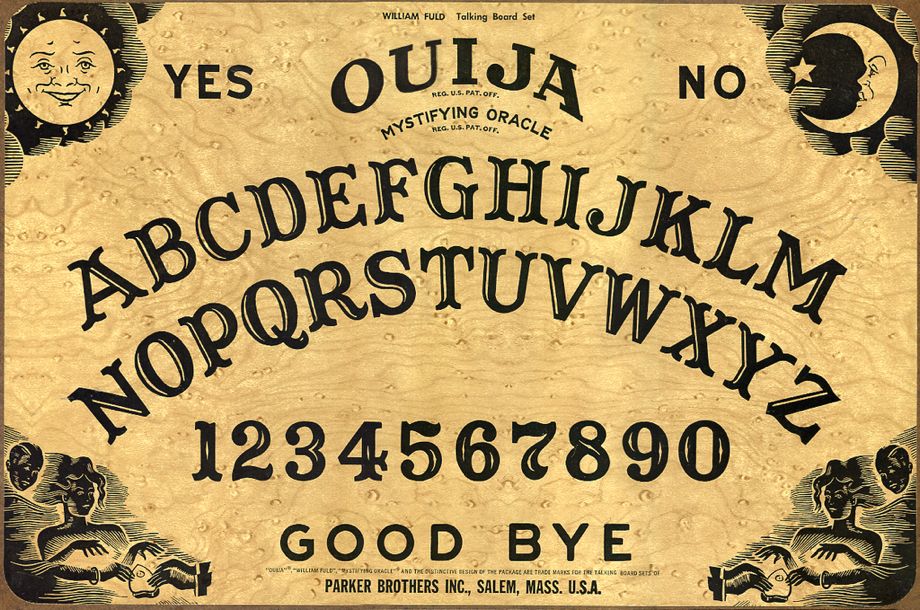

The Ouija board is so simple and iconic that it looks like it comes from another time or maybe another realm. The game is not as ancient as it was designed to look, but those two arched rows of letters have been spooking people for more than 125 years. Actually, the roots of the board go back even further, according to Ouija historian Robert Murch. To understand where Ouija boards (generically called “talking boards”) come from, you have to go back to the middle of the 1800s, to three sisters in New York.

The Fox sisters claimed to be mediums to the spirit world. In public demonstrations, they would ask questions of the spirits and receive audible knocks back on the wall, which they would translate into letters of the alphabet. The sisters popularized the growing movement known as spiritualism, which held that the living could contact the spirits of the dead, who had secret knowledge to impart.

During and after the Civil War, people who had lost loved ones became enchanted with the idea of communicating with the dead and came up with all different ways to contact the spirit world. In 1886 the fledgling Associated Press ran an article in papers all over the country about these new “talking boards” coming out of the spiritualist movement in Ohio. A few years later in 1890, a businessman named Charles Kennard pulled together a small group of investors and formed the Kennard Novelty Co. to exclusively make and market talking boards.

Via Wikimedia Commons

Contrary to popular belief, the name Ouija is not a combination of oui and ja—the French and German words for yes. According to original documents belonging to the founders of the company, they asked the board itself what it wanted to be called. Letter by letter, it spelled out O-U-I-J-A. When they asked the board what that meant, the board spelled out “good luck.”

By 1893, original founder Kennard was out of the company and an employee named William Fuld had taken it over. Fuld would come to be known as the “father of Ouija.” He didn’t invent the board, though he sometimes gets credit for doing so. He was just incredibly good at selling it.

Fuld was intentionally mysterious about whether the board worked, how it worked, and whether it was just a game or a more serious spiritual tool. This marketing strategy was extremely successful, and everyone had to have an Ouija board. People played at home with their families, including their kids, which may seem strange now.

In the late 1800s continuing all the way into the 1960s, the Ouija board was considered good, clean, family fun.

Ouija, it turned out, was also a great thing to do on a date. The original Ouija board was placed on your lap, so your knees would be touching your partner’s knees. Your fingers would be touching your partner’s on the planchette. You might be playing by candlelight. However romantic Ouija may have been, it was still innocent enough for Norman Rockwell, who made a painting of an Ouija-playing young couple that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post.

Ouija always had a few naysayers who warned about the secret powers of the board. Some of the first and loudest critics were actually mediums, whose jobs these “talking boards” had stolen. Still, for the most part, the Ouija board maintained its wholesome reputation until the movie the Exorcist. Released in 1973, the main character becomes possessed by the devil after playing with a Ouija board by herself at the beginning of the movie. In the following years, the Ouija board was denounced by religious groups as Satan’s preferred method of communication.

There’s a new Ouija movie, released on Friday, which will do nothing to change the board’s sinister reputation. In it, a teenage girl is mysteriously killed after a bad experience with an Ouija board. Ouija’s new, darker reputation is fine by Hasbro, the company that now owns the game. In fact, they seem to be playing up the scary side of Ouija. The tagline on the packaging used to be, “It’s just a game, isn’t it?” Now, when you open the game, the first thing you see is: “Don’t play Ouija if you think it’s just a game.”

In 2013, a new version of the Ouija board was redesigned to look even older than the classic board. “They’ve really gone for the older look,” says Ouija historian Murch, “which is cool because people assume these boards have been around for thousands of years, which we know isn’t true, but belief is important to the Ouija board.”

Belief is very important to the Ouija board, especially subconscious belief. Which brings us finally, to how these things work. In 1852, an English physician and researcher named William Carpenter was studying spiritualist phenomena and coined the term ideomotor effect. The ideomotor effect describes what happens when subconscious thoughts guide muscular movements.

According to professor Chris French of the Anomalistic Psychology Research Unit at Goldsmiths, University of London, the ideometer effect can explain why, on the Ouija board, the planchette seems to be moving on its own. In truth, the players are guiding its movement subconsciously.

Some researchers have even tried to study the subconscious using Ouija boards.

“I don’t have any doubts in my mind that we can explain the vast majority of ostensibly paranormal experiences by looking to psychology,” French said. “Whether or not we can explain every single one is the $64,000 question.”

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.