Why LGBTQ Film Prizes Like the Berlinale’s “Teddy” Still Matter

Hard Working Movies

At the 66th Berlin International Film Festival, which wrapped up late last month, you couldn’t walk a mile in any direction around Potsdamer Platz without overhearing talk of immigration and refugees. At a press conference for the opening film, the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar!, George Clooney was even grilled by a Mexican journalist who wanted to know what, specifically, “he was doing for the Syrian refugees.” And in the most fitting dénouement imaginable, Italian documentary filmmaker Gianfranco Rosi’s Fuocoammare—an intimate snapshot of the migrant crisis unfolding on the Mediterranean island of Lampedusa—took home the top prize.

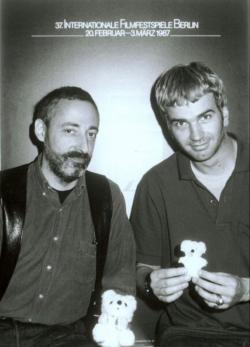

Berlinale Panorama programmer Wieland Speck was also thinking about refugees, but in a slightly different frame. Speck is co-founder (along with filmmaker Manfred Salzgeber) of the Teddy Award, a prize established in 1987 to recognize excellence in LGBTQ-themed films presented at the Berlinale. “Everybody is talking about integration and refugees, but the biggest group of refugees ever is queer people,” Speck tells me when we meet on the day of the Queer Academy, a conference that brings together some 300 filmmakers and festival organizers from around the world. “We have queer refugees who get harassed by other refugees who aren’t their kind. So we have to make sure that in our countries, queer refugees are safe. This confirms the observation that hardly any queer person spends their life in the place where they grow up. We deroot ourselves in order to reinvent ourselves. That implies a transfer of creativity that has an immense cultural impact.”

Berlinale 2016/Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin

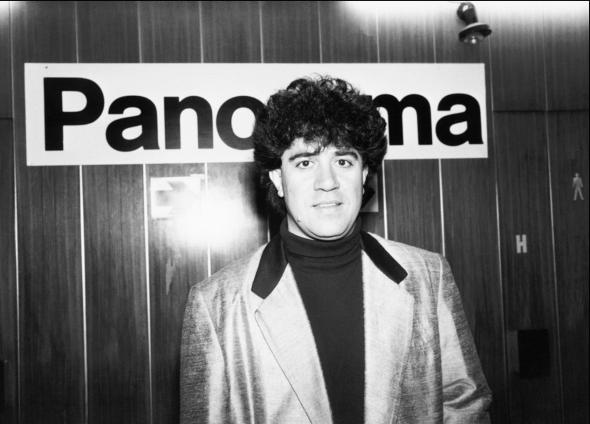

Speaking before an audience assembled inside the stunning historical landmark Station-Berlin earlier that morning, Speck held back tears as he took stock of all that had been accomplished: “Thirty years ago, we did not even anticipate to be around for so long. For many of us were dying of AIDS exactly then—and the same group gathering today for this summit was merely 15 people strong. But it was the first jury for the first Teddy Award.” Along with the fact that the Teddy was the first out the gates, what’s most impressive is that it has remained the most prestigious and prominent queer film award at any major festival. Over the years, an incredibly varied selection of artists have received the burly statuette—filmmakers such as Lisa Cholodenko, Todd Haynes, Tilda Swinton, Rosa von Praunheim, François Ozon, Jay Duplass, James Franco, Jennie Livingston, Gus Van Sant, and Pedro Almodóvar (the latter two, in their earliest 1987 incarnation as department store-purchased stuffed grizzlies). Following the Berlinale’s lead, organizers in cities such as Rio, Kiev, and Guadalajara, as well as top-tier festivals like Cannes and Venice, now also hand out distinctions to the best queer offerings annually. “You had to set up something that worked for the mainstream view—[so] that the mainstream culture could recognize what you do,” recalls Speck, about the decision to include LGBTQ honors at a mainstream festival.

Erika Rabau/Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek/Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin

Commendably, the LGBTQ-themed films programmed at the Berlinale aren’t segregated from the broader line-up, sending the message that these titles aren’t merely of niche interest, but of potential appeal to all. As part of the ‘Teddy30’ retrospective, Speck programmed a whole slate of rarely seen LGBTQ-themed films that predate the Teddy’s very existence—films like Richard Oswald’s newly restored Anders als die Andern (Different From The Others, 1919), the first feature to openly depict gay men (and in a sympathetic light, no less), co-written by and starring Magnus Hirschfeld, one of the founding fathers of sexology and the gay rights movement. Looking at it nearly a century later, the Berlin-shot film is a fascinatingly levelheaded defense of homosexuality. The film’s protagonist Paul Körner is a violin virtuoso subjected to the repeated threats of a callous extortionist, who takes full advantage of Germany’s Paragraph 175, a law that made male homosexuality a criminal offense. Particularly sobering is the film’s opening scene, which finds Körner flipping through newspaper obituaries to read about several men who’ve mysteriously and tragically committed suicide. The musician reads between the lines and understands that Paragraph 175 made life simply too unbearable for them.

Edition Filmmuseum

At the Queer Academy, Speck reiterated the urgency to restore, digitize, and distribute endangered analogue film stock—particularly important documents such as Different From The Others. Having them around for future generations is crucial if we’re to acknowledge the full breadth of queer film history—the staggering hardships and the hard-fought battles that defined previous LGBTQ trailblazers. It’s something 2015 Cannes Queer Palm jury president Desiree Akhavan (Appropriate Behavior) echoed on the French Riviera last spring when she explained, in response to filmmakers who dismissed the very notion of a queer prize: “In queer cinema I found confidence in myself and strength while I was coming out and tried to understand what being gay meant and how it would influence my life.”

It’s something Dutch filmmaker Reijer Zwaan reiterates when I ask him about the importance of the Teddy. Zwaan was in Berlin to present Strike a Pose, a documentary he co-directed with Ester Gould about the legacy of Madonna’s Blond Ambition dancers, 25 years after they inspired fans the world over to express themselves. “We’re lucky to live in a time when there is much more visibility than, let’s say, 25 years ago, but many kids still grow up without seeing many gay people they can look up to or respect. We’re lucky that it’s moving in the right direction, but it’s also not something to take for granted.”

Zwaan, a political scientist and editor of a current affairs program in the Netherlands, describes Strike a Pose as a “happy departure,” thematically speaking—one that stems from his fascination with the dancers as an impressionable young kid. “I was 11 years old when I saw the film in Amsterdam. I remember how inspiring it was to see a group of gay guys so open, proud and cool, on the road with Madonna. At the premiere in Berlin, many audience members expressed how because of the dancers, they came out or dared to be themselves, and it was really touching to hear that.”

Lisa Guarnieri

New York-based producer Christine Vachon (Carol, Boys Don’t Cry, Todd Haynes’ entire oeuvre), who was honored with a Special Teddy Award at this year’s festival, remembers winning her first Teddy in 1991 as quite the surprise. “What I find really amazing is that 30 years ago, the Teddy existed,” she told a capacity crowd during the Queer Academy. “When Todd [Haynes] and I got to Berlin with Poison, we were told there was this award you could win for a gay movie—in a film festival that isn’t gay. That alone felt really revolutionary at the time.”

Vachon, whose films have won three Teddies since (Swoon, 1992; Go Fish, 1994; Hedwig and the Angry Inch, 2001), recalls how an inherently experimental film such as Poison managed to pull in surprisingly strong box-office numbers in the early 1990s, because LGBTQ audiences were so desperate to see their lives reflected on the big screen. “At its heart, Poison was an extremely experimental film, but people showed up in droves to [New York’s] Angelika Theatre. Of course, they weren’t expecting something so experimental, and I remember standing outside the theatre, and all these people coming out and going, like, ‘whaaat? I thought I was going to see some boys kissing! What was all that?’”

Zwaan and Vachon raising the crucial issue of LGBTQ visibility only reaffirms the Teddy instigators’ original impetus for launching the prize: to encourage the development of a queer film movement, both in Germany and abroad. Poring over the wide-ranging queer offerings at this year's Berlinale, one can appreciate how far the initiative has come in three short decades. For one, the sheer diversity of identities, ethnicities, and age ranges now represented at a festival like the Berlinale serve as a testament to the wealth of queer storytelling out there. Among them, a South Korean documentary about a gay male choir in fairly conservative Seoul and their creative choreographic tendencies (Weekends); a fictionalized retelling of the last woman to be publicly executed in Czechoslovakia, after violently lashing out at the society that rejected her (I, Olga Hepnarova); and an exploration of underground Chinese marriage-of-convenience markets for gays and lesbians looking to satisfy their parents’ heteronormative wishes (Inside the Chinese Closet).

Kiki, the winner of this year’s Teddy for Best Documentary, provides an update of sorts on New York’s vibrant ballroom scene, which we were first introduced to a quarter century ago via Jennie Livingston’s Paris Is Burning (which, incidentally, also took home the Best Documentary Teddy). But in Sara Jordenö’s Kiki, the voguing antics take a backseat to the social and political activism of a youth welfare organization working to support homeless, impoverished, or otherwise struggling LGBTQ queers of color. The film, shot over a four-year period, broaches the marriage equality victory that occurred over the course of filming—and how that moment served to exacerbate the systemic inequalities within the LGBTQ movement.

When asked how the social landscape has shifted since Paris is Burning first exposed audiences to Harlem’s ball scene competitors, the Swedish filmmaker points to how we now live in a world that recognizes and celebrates talents such as transgender performer Saga Becker, who won the Best Actress prize last year at the Guldbagge Awards, Sweden’s equivalent to the Oscars. Yet she also recalls the marginalization she experienced back in visual arts school. “I was making art that dealt with queer politics and my teacher would say, ‘This will ruin you. You can never make it in the art world if you have queer content; it’s like a poison in your work. The mainstream will never accept it.’ I was like, are you kidding me! So that just showed systemic oppression in the art world.”

Garagefilm International

The notion that queer history has consistently been marginalized by the mainstream is one Speck wholeheartedly subscribes to. “We’re not part of any history class in school or university,” he says. “Of course, we’ve always existed in every culture around the same percentage… Seeing it from that perspective, it’s an amazing denial that mainstream culture behaves in, and it’s totally non-democratic because it’s the dictatorship of a majority. Why doesn’t Germany put out more queer films, for instance? The same question could also be: Why aren’t there more female filmmakers? I think there’s a lot of marginalization. The guys who ‘know’ what a good film is, what will ‘make it’ at the box-office, etcetera, are basically white male heterosexuals.”

While many like Speck have fought for increased visibility and legitimate representation at the decision-makers’ table, the queer community has never been a totally homogenous bunch. Among such a varied group of individuals, people are bound to disagree. And that’s something Speck seems at peace with. “When you fight for rights, you always fight for people who are not fighting and yet will profit from it later. This is automatic. You fight for people that you might not even like. I mean, you have LGBTQ bankers now who can call themselves ‘gay’ in everyday life and marry, but they never did anything to fight for that. That’s just the way it is.”

Berlinale 2016/Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin

Since its infancy, the queer film movement has also had to contend with certain filmmakers and cinephiles’ reluctant or downright dismissive stance towards LGBTQ festivals and awards. "They shouldn’t exist" is the oft-repeated mantra, with the ghettoization argument generally brought up by those who reject the very notion of a queer prize. Ironically, among the films being fêted as part of the Teddy30 retrospective this year were two landmark works by recently departed Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman. While openly lesbian, Akerman famously said that she would “never permit a film of mine to be shown at a gay film festival.”

Donald Weber/Getty Images

Still, Speck tells me there was no hesitation on his part to include two films from the pioneering, boundary-breaking director in his retrospective. “She was my friend, and she is a filmmaker who inspired me to create the Teddy, and we showed her film [Toute une nuit (A Whole Night)] in 1983, which was the third year of the Panorama section. She’s someone very close to my heart.” Looking back on her position vis-à-vis queer cinema, Speck explains that she had a profoundly anarchist mindset. “She was not dogmatic. She would have said that at a certain period in her artistic life, she didn’t want to be boxed in. That said, being in the Teddy30 retrospective in the year 2016 in Berlin is not boxing or cornering her in any way. This is my attitude.”

For Nairobi-based filmmaker Njoki Ngumi, whose Stories of Our Lives docu-fiction hybrid won a Teddy last year, the question of whether to hand out LGBTQ-specific prizes is akin to asking the queer community why it still feels the need to celebrate pride. In sum, it’s disingenuous. “It doesn’t recognize the amount of work that’s been done to identify the existence of hegemonic structures that work to keep out marginalized populations,” she explains. “Just when these populations are starting to find their niches that work, the critique that they shouldn’t have to, for me, is a little unfair because it references a false utopia.”

Ngumi recognizes that some marginalized folks want an alternative space, while others might want greater inclusion in the mainstream narrative—and that there should be room for both perspectives. One shouldn’t cancel the other out. But she strongly feels that film programmers of all persuasions have a responsibility to showcase the world in its true diversity, instead of merely representing whiteness, masculinity or heterosexism. “Everybody has a lot of growing to do with regards to representing a world that exists, and not the world that particular filmmakers with Hollywood clout necessarily want to tell you about.”

It’s a sentiment shared by Speck, who talks of festival programmers’ ethical imperative to celebrate a diversity of orientations, identities, ethnicities, and age ranges. “Of course, I want to show more lesbian films, but that’s not an ethical question. It’s rather attributable to an injustice that I myself cannot solve. Nevertheless, I put extra effort in. And of course, we put a lot of effort in terms of getting films from Africa. It’s of course much more convenient to just wait and see what you receive as submissions, and then just take what you like. But our programming on a whole is far more responsible than that.”

Indeed, as long as homophobia and transphobia remain on the radar somewhere on the planet, and LGBTQ citizens are subject to persecution and violence—even in Berlin itself, as was pointed out by Speck—prizes such as the Teddy remain a powerful tool to shine a spotlight on the plight of vulnerable populations. And, as continues to be the case, simply to provide much-needed visibility to marginalized groups, as Kiki ball performer Gia Marie Love so eloquently made clear a few days prior to the film’s Best Documentary victory. “The film community and the media in general have a moral obligation to tell the stories of queer people of color around the world, and queer stories in general,” she argued. “The media affects the way people are treated and the way they want to live their lives. Me seeing images of marriage, happiness, and nuclear families is the reason why I wanted one growing up. And, especially as a trans woman, we’ve started to have this conversation around fictional trans characters that are progressive, positive, that have families and are in love, because people are scared to love us. We need to have this conversation.”