The Play’s the Thing? Homeless Transgender Youth Act Their Way Toward Justice

Credit: Will O'Hare

A woman pulls herself up off the floor, clutching her abdomen, and staggers over to the door—it has already been a long night of unpleasant surprises, and now the NYPD is knocking. Noise complaint, two officers bark. “Mind if we come in for a minute?”

The woman hesitates, touching the bruises on her face. Then she steps aside. While she tries to explain that her abusive boyfriend has already fled the scene, one of the officers searches the apartment and comes across a syringe. This is enough, in his opinion, to justify an I.D. check—Andrea T., female. Never mind that the woman is clearly injured, or that the syringe is for hormones. The officer hangs up his radio and calls over to his partner, chuckling: “Downtown says that this It right here is actually a man.”

“A man?” his partner sneers, stepping back to take a better look at Andrea’s long braids and short shorts. “Are you serious? With an ass like that?”

This scene—which would end with Andrea being dragged off to the station in handcuffs—played out in early May at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community Center, in New York’s West Village. It was part of a theater performance, most immediately; but it was also drawn from the real-life experiences of a troupe of actors, mostly transgender, who are clients of the Ali Forney Center, a nonprofit agency that offers, among other services, emergency and transitional housing to LGBTQ homeless youth in the city.

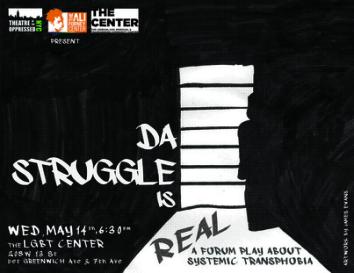

For more than two months these actors had worked on a play—titled Da Struggle Is Real: A Forum Play About Systemic Transphobia—as a means of grappling with personal struggles with discrimination, domestic abuse, sexual assault, and police brutality. Now they were staging it publicly with the expectation of a response, practical as much as emotional. “How many people in the audience have problems?” an emcee asked at the start of the show. “We made a play about ours, because we don’t want these problems to stay the same, and that’s the reason you’re here.”

Art by James Evans.

Audience engagement is key in “Theatre of the Oppressed,” a social justice–focused school of dramaturgy of which Da Struggle Is Real is an example. Augusto Boal, Brazilian artist and activist, developed the performance methodology in the 1960s based on his theory that performance could empower the underclass. “Theatre is a form of knowledge,” he claimed. “It should and can also be a means of transforming society. Theatre can help us build our future, rather than just waiting for it.” In a kind of founding manifesto he was even more explicit: Theater, he wrote, is “a very efficient weapon.”

Weaponizing theater in Boal’s sense starts with persuading spectators to get out of their seats. At the close of a play, the audience brainstorms strategies for combatting the injustices they’ve just seen on stage. Volunteers then step up, assuming the place of the protagonist—shouldering a handbag, for example, to become Andrea—and test out their ideas in a kind of performative Groundhog Day, repeating scenes in an attempt to improve the outcome. For proponents of Theatre of the Oppressed, this process of communal problem solving has the potential to be revolutionary. It has been used with prisoners in Argentina and Palestinians in Jerusalem, and to confront “dowry deaths” in India. In New York, a case manager at the Ali Forney Center told me, “It seems like no matter what our youth are doing, they don’t get the benefit of the doubt from the community. They’re criminalized just by being themselves.” Theatre of the Oppressed aims to short-circuit this conflict, offering the actors an outlet for their grievances while encouraging the community to step into their shoes, seeing things from the minority perspective.

But a change of heart can do relatively little to help the Andreas of the world if policy doesn’t change along with it—which is why two weeks after this performance in the center, a festival of Theatre of the Oppressed, called Can’t Get Right, would try to elevate the stakes. Focusing on racism and demographic profiling in the criminal justice system, Can’t Get Right promised to stage select scenes from plays like Da Struggle Is Real (including Andrea’s altercation with the police) for an audience including representatives from the New York City Council and the federal government. Not only would this audience be expected to propose solutions for the semi-fictional Andrea; they would also brainstorm and vote on policy proposals that could impact the lives of the actors directly—proposals that would then be taken back to City Council for serious consideration. The transgender actors hoped to do more than educate and entertain here: They hoped to change actual law. The question was, with all of them subject, on a daily basis, to tremendous trials and challenges, could the troupe stay together long enough to seize the opportunity?

* * *

Though Theater of the Oppressed rejects the idea of a traditional production director, it still takes a strong personality to juggle so many uncertainties and keep everyone focused on the goal. In this case, that person is Katy Rubin, a 28-year-old firebrand who found herself chafing at the kinds of activism she was seeing in America. “Many folks who were activists were really separate from the communities they were talking about,” she told me recently.

Rubin has a background in theater and circus arts, and in 2008 she traveled to Rio de Janeiro for a residency at Augusto Boal’s Center for the Theatre of the Oppressed. It was there that she met his “Jokers,” so called because they remain neutral (like the card) as they guide troupes of actors through the theater-making process. Rubin observed Jokers working at the grass-roots level, with people in impoverished communities, and institutionally, with mental health practitioners and government departments.

There was nothing this expansive in the United States, where Theatre of the Oppressed is largely restricted to university classrooms. As Rubin returned to New York, she wondered what would happen if she tried to change that, replicating the wide-reaching model of Brazil. Though she had no initial plan for how to achieve this, Rubin took Boal’s essential ideas about theater and deployed them through an organization of her own, Theatre of the Oppressed NYC, which she officially founded in 2010. Since then, almost organically, TONYC has established itself throughout the city via word of mouth. Community groups and city agencies hear about the theater process and approach Rubin’s small team to establish troupes that can investigate the struggles of their own clientele. In this fashion, TONYC has forged partnerships with the likes of Housing Works, the NYC Housing Authority, the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services, and the Ali Forney Center, creating troupes of undocumented immigrants, the recently incarcerated, HIV-positive New Yorkers, and LGBTQ homeless youth.

Credit: Will O'Hare

Rubin’s vision as artistic director eventually expanded to include partnering with city agencies like the Department of Probation and the Department of Homeless Services, so that, she told me, “the plays are immediately reaching the people who are making policy.” There is clear evidence this is working, too: Last year, at the first festival of Theatre of the Oppressed in the city—the precursor to Can’t Get Right—NYC Council Majority Leader Jimmy Van Bramer watched a forum play about stop and frisk in which young trans women were harassed by the police. “It really helped solidify my thinking on that issue,” he told an audience in October, drawing a direct line between the performance and his vote for the Community Safety Act, a landmark piece of law enforcement discriminatory policing reform.

Van Bramer was slated to attend this year’s festival as well, but Rubin had been canvasing hard, and he would be joined by City Councilman Carlos Menchaca from District 38, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the U.S. Department of Justice. There would also be a packed policy advising team of union leaders and community defenders. All of which is to say, as Rubin well knew, a lot of important people were coming to see what these young people had come up with.

* * *

A great deal of sweat and some tears have been shed in recent months above the Popeye’s Chicken and Biscuits in Harlem. It was here, every Wednesday during the period of development for Da Struggle Is Real, that the troupe rehearsed in the “art therapy room” of the Ali Forney Center, tripping over sliced-up magazines, unspooled tape, and half-empty bottles of paint. “It’s like a clown car,” John Leo said one morning, dragging out a table to clear some space. “We’re going to have to fit a lot of people in here.”

Leo was the troupe’s Joker for the season, a colleague of Rubin’s at TONYC. Bald and tall, he moonlights as a hospital clown and has the sort of face that stretches into big, elastic expressions, like a commedia dell’arte mask. The workshop process for the Ali Forney troupe, he once told me, is “theater in the trenches”—demanding work. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t also fun. “Theatre of the Oppressed,” he said. “Not Theatre of the Depressed.”

It was mid-March, and Leo was wearing a blue hairy sweater over an orange button-down. As the troupe members began to wander in, he changed into a T-shirt with “Everyone is a Spect-Actor” scrawled across the front. (A “spectator” merely watches; a “Spect-Actor,” in Boal’s terminology, gets involved.) Nobody paid much attention, though. Leo’s aide was reading out a flier he’d found in the waiting room outside. “Who’s going to try out for the AFC talent show?” he asked. “Twerk for Jesus.”

“Twerk for Jesus!” squealed a young woman, twerking.

Niobe shrugged off her bag and sighed dramatically, her dark hair pinned up in an impressive pile of cumulus cloud–like puffs. Lotus glided straight to the wall, declining to remove a pair of giant white sunglasses. James, a 19-year-old artist, quietly took a seat near the window, turning to watch the other actors stroll in. There were eight in total, energetic and strong-willed, which was good for the theater but a challenge to wrangle. Leo knew he would have to tread carefully here. “You cut me off, and I said something very intelligent,” one actor snapped early on.

“I wasn’t cutting you off because you weren’t saying something intelligent,” Leo replied calmly. “It’s because of the rules of the game.” There were several games to start, designed to polish improvisation skills, or simply remind everyone of names and “PGPs”—preferred gender pronouns—which changed for some members on a daily basis. (James, for example, was consistently “he,” while Lotus went from “she” to “don’t care” to the ambiguous but compelling “flowerbomb”). These games soon gave way to the week’s task, which on this particular morning meant identifying common struggles and then expressing them through art projects—sculpture, drawings, and poetry. Scene-building would come later, after the troupe had narrowed down its story selection. Making art, Leo explained, would help them locate “the feelings of these stories.”

A young man nodded that he understood. “Basically, I want to do something on abusive relationships,” he said, as soon as Leo gave the signal to begin.

“It’s real!” said the girl on the floor beside him. But a Latina trans woman shook her head.

“You’ve never been in an abusive relationship?” the man asked.

“Nah,” she replied. “I mean, I don’t recall it.”

“I don’t recall it!” mimicked the girl on the floor, rolling onto her back and laughing wildly.

“Then what about police brutality?” the man said. “You never got beat up by the cops? I know I did.” He punched his fist into an open palm.

Before the Latina woman could answer, another man, sitting on a chair and listening quietly as he ate a box of Peeps, jumped in with his own opinion, saying, “I could go either way, the abusive thing, the police brutality thing.” He paused for a moment, mulling something over. “Is it still considered an abusive relationship if you both abuse each other?”

Credit: Will O'Hare

Watching from the sidelines, I quickly realized that any one of these young people could furnish enough material for a play on their own. The challenge wasn’t finding topics; it was narrowing them down, figuring out what best fit the lineup for a play that represented everyone. Take James, who was sitting on the other side of the room concentrating on a sketchpad, his short hair gathering in a Tintin-like wave above black-rimmed glasses. One of the first things I noticed about James was two tattoos on his left arm: a northern star, and, in large typewriter font, This too shall pass. James later explained that these were reminders of his “freedom day”—Jan. 3, 2011. That was the day he’d withdrawn his life savings and caught a Greyhound bus from Virginia Beach to Albany, escaping religious parents who rejected his trans identity as a malignant influence on his younger siblings and a grandfather who once asked him, “If you’re never going to be happy, why don’t you just kill yourself?”

James’ “freedom” since then had been a bitterly ironic kind of liberation. Homeless shelters in Valhalla and New Rochelle, New York, had exposed him to ridicule and transphobic abuse. Employers had spurned him, too, including a Boys and Girls Club that seemed to be interested and then very suddenly wasn’t (“We decided to go with someone more experienced,” the recruiter told him, in what James later discovered was a lie). Throughout it all, James struggled with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and a feeling of invisibility in the LGBTQ community. “It’s not that I think trans women should be talked about less—I definitely don’t think that,” he told me. “But trans men aren’t talked about at all.” Recently, James had fantasied about moving to Detroit, finding a house to squat in, growing his own food in a vegetable garden. But that sort of thing requires planning, and plans are tough when you live in a basement shelter in Queens that locks you out at 8 a.m. every morning.

James’ story isn’t unusual for the clientele at the Ali Forney Center—or the homeless youth of New York, up to 40 percent of whom are LGBTQ. Most of their Venn diagrams overlap when it comes to trauma. But Leo explained that the theater-making process tried to turn this overlap into the catalyst for camaraderie. “It’s amazing to see people come out of their shell and connect,” he said. “They feel like, ‘OK, this is happening. It’s not just me.’ ” For many of them, even being in a space where they’re conceptualized as capable of writing a play and commanding a sympathetic audience is something they’ve never experienced before—something revelatory.

* * *

Still, as rehearsals inched through March and April toward Can’t Get Right at the end of May, a number of actors skipped weeks or dropped out entirely. There were myriad reasons for this: job scheduling conflicts, bad nights in the shelters, public housing interviews, altercations with the cops, episodes of mental illness. Life got in the way, and I watched the troupe slim down to a handful of core members. “We’ll make it work,” said Penny Ferrer, an intensive case manager at the Ali Forney Center. “It’s kind of how everything is here.”

Credit: Will O'Hare

Leo remained upbeat, or tried to anyway. Though he became more businesslike as the weeks progressed—he called it “putting my choo-choo hat on,” like a train that’s leaving the station and picking up speed—he made sure to stay encouraging and open, working with anybody who turned up for Wednesday rehearsals. One week that meant Ed, the Ali Forney social work intern (also transgender), and James, who glanced around the empty room before remarking, with characteristic wryness, “They should all get thrown out and I should get all the parts.”

Leo let the comment slide, preferring to rally enthusiasm under the circumstances. Today he wanted to start with the news: Had James or Ed found any articles that resonated with the play’s themes? Ed pulled up a seat, then cited the case of CeCe McDonald, a black trans woman who had recently been released after spending 19 months in men’s prison for killing Dean Schmitz. Schmitz, a 47-year-old white man who attacked McDonald and her friends on a street in Minneapolis, was found to have a history of domestic violence and a swastika tattooed on his chest, which the judge declined to admit as character evidence. The judge did admit McDonald’s prior conviction for a bad check, though. James was indignant. “Clearly, if you’re poor, you’re a murderer,” he fumed.

This was the sort of passion Leo was looking to harness, and he snapped the focus back to the play. “Where are we in terms of writing?” Ed asked.

James described the scenes that had been approved by the troupe, including the altercation with the NYPD and another one that sounded particularly familiar: Andrea, who would be played by Tara, applies for a job at a child care facility only to be told after a successful trial shift that the position is already filled. In the next scene, Andrea finds out the job isn’t filled, that she was lied to, with the facility still desperately searching for new employees.

“Didn’t this all happen to Niobe?” Ed wondered aloud.

James fell silent, saying nothing about his own experience. Leo simply shook his head. “These stories happened to so-and-so,” he said carefully. “But they’re happening to us. We all identify with the emotion.”

If there’s one main idea that drives the engine of Theatre of the Oppressed, it is Leo’s emphasis on solidarity. Many of Boal’s techniques are supposed to promote trust and common understanding among the actors, but the theater-making process has larger goals. One day over coffee in Park Slope, Leo explained this by recounting some of the personal dilemmas people face in their early days of facilitating as a Joker. Doubting their right to be doing the job, they ask themselves questions like, “How can I be here? I’m white and middle-class. I came from Westchester. How can I help these people?” As you engage with the actors, Leo explained, you come to see that you aren’t helping them, exactly. “They are helping me,” he said. “We’re helping each other.”

He was referring to community-mindedness: Participants (especially an audience) are encouraged to see themselves as part of a social structure that “can allow these kids to be kicked out of houses.” See yourself as connected to that, the rationale goes, and you’re more inclined to want to do something about it. Leo called solidarity “a muscle in the body that is atrophied,” saying, “it needs to be exercised.” He held himself up as a case in point: While never considering himself much of an activist prior to becoming involved with Theatre of the Oppressed, he now finds himself attending protest marches for a variety of issues.

Leo is just one example, of course, but when I spoke to Katy Rubin, she described her intentions behind TONYC as this kind of perspective shift writ large. Her “secret agenda,” she said, has been to turn solidarity into “a fad.” This would be no small feat in a city—and indeed, a country—that runs on a mantra of self-reliance and ambition, with every man out for himself.

* * *

On May 30, Andrea’s boyfriend beat her to the floor again, a noise complaint was lodged, and the police returned, banging loudly on the door. Andrea was interrogated in her home, hormone injections were discovered in the back room, her I.D. was cross-checked, misunderstanding fueled transphobic abuse, and the scene ended, once more, in handcuffs and humiliation.

The difference this time was the audience. It was a warm spring evening, and more than 150 people were gathered for the main event of Can’t Get Right in a small gymnasium in the West Village owned by the Church of Saint Luke in the Fields, a co-sponsor of the festival.* Rubin set a tone of playful officiousness: Dressed in a black suit with a badge on her lapel, she held a clipboard and gavel, looking like a speaker at a political rally as she outlined “the order of business.” The crowd listened intently, while policy advisers sat by Jimmy Van Bramer and Carlos Menchaca along the wall. “Just remember,” Rubin said, “when it becomes overwhelming, we have come here with a job to do.”

The festival was designed to showcase performances from three different TONYC troupes—Housing Works, CASES, and Ali Forney—but after the Ali Forney actors ran their scene from Da Struggle Is Real, John Leo jumped up to engage the crowd about the performance. “Who saw Andrea facing problems?” he asked. “Are these problems real? Who wants these problems to stay the same?”

“No!” the audience shouted. The scene had left people visibly rattled, and the atmosphere was tense. At Leo’s encouragement, a young Latino man said he had an idea and stepped up to the stage to substitute for Tara. While he pulled a handbag over his shoulder, the other actors assembled around him in their usual positions. Leo counted down: Three, two, one, action. The cops banged on the door. “Mind if we come in for a second?”

“No,” the Latino man said. “You stay there.”

Suddenly, the scene recalibrated. The first cop enquired about the noise complaint, then the physical abuse, but he was clearly caught off-guard. “Listen,” he said, “it would be easier if we came inside to take a look around.”

“No,” the man repeated, making Andrea even more assertive; consent would not be given. At this, the audience exploded, applauding and whistling. The hormones would never be found now, Andrea’s gender would not be interrogated, and there were witnesses in the hallway watching the interaction. In the universe of the play, this represented a rousing triumph against the authorities.

But was this a viable strategy outside the theater? Could a real-life Andrea rebuff hostile officers demanding entry to her home? The ambiguity of the situation was something most people in the crowd seemed to recognize pretty quickly. “I think the NYPD needs more training in how to deal with gender identity issues,” one woman suggested after the Latino man returned to his seat. An older man had a different idea. “I think there should be classes about our rights,” he said, “because we don’t really know what they are, or what we should say.”

This was the real business of Can’t Get Right. Rubin returned to the stage and encouraged the crowd to write down their ideas on pieces of paper that had been distributed in the programs. These ideas were gathered, sorted, and evaluated by the policy advisers and government reps on the side of the room; the best of them were then brought to the floor. Having watched the scenes and brainstormed solutions, the audience would now vote on a range of real-world proposals, including body cameras for active police officers, requiring a form of written consent before searches, the ability to alter birth certificate gender, and municipal I.D.s that would make it easier for trans people to be identified correctly. Some of these ideas were already being discussed at the City Council level; others were entirely new. After each proposal, the audience held up green or red cards (yes or no) while aides moved around the gymnasium to tally up numbers.

Credit: Tiph Browne

Van Bramer and Menchaca took turns presenting the proposals. “What a great opportunity for us to shape legislation in a whole new way,” Menchaca said. “It’s great to see Theatre of the Oppressed in all it’s glory. I can’t wait to bring this back to the City Council.”

Van Bramer, standing beside Rubin, was even more effusive. After being swayed to vote for the Community Safety Act in 2013, he awarded funding to TONYC to further its community work. Now, as the evening wound to a close, he announced that every proposal had been accepted by consensus. “You guys take art and theater and performance, and make it so powerful,” he said. “You change the lives of the actors, and everyone here is claiming power, and owning power. And it is a beautiful thing.”

As I sat in the audience wondering how far these words would travel, the actors gathered around the two city councilmen, and Tara draped her arm across Van Bramer’s shoulder. It was a curious tableau: disadvantaged actors, politicians, and policy advisers huddled together on a makeshift stage. A photographer stepped up and took a photo. The audience was breaking up by that point, drifting out through open doors. Rubin, with harried urgency, had tried to hold their attention until the very last moment. “The council members and the policy writers will keep us up to date on what happens with these ideas,” she said, projecting her voice to the back of the room, making sure everyone knew that things wouldn’t end here, that this was just getting started. "And we will keep you up to date. It’s really important, yeah? We want to keep this conversation going.”

*Update, 6/12/14: This post has been updated to reflect that, in addition to hosting the Can't Get Right Festival in their gym, the Church of St. Luke in the Fields co-sponsored the event.