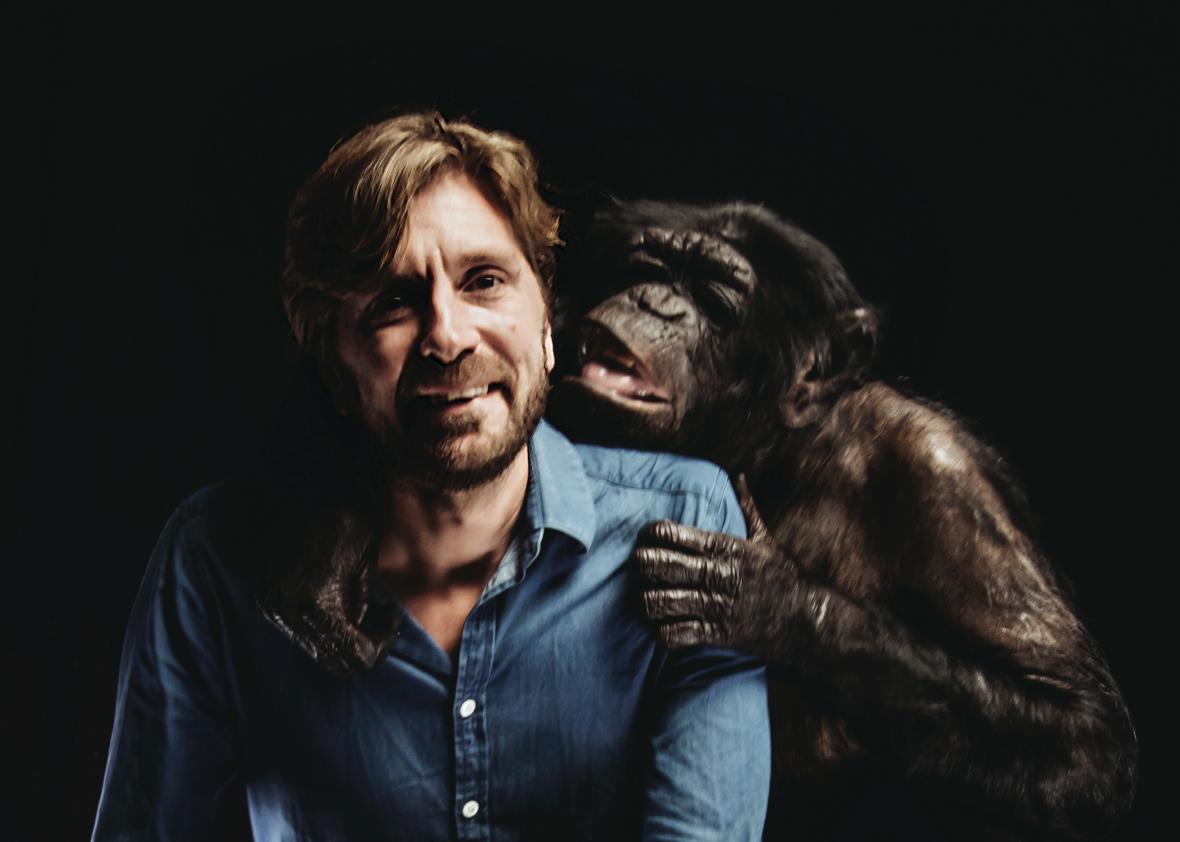

The Square’s Ruben Östlund on the Social Contract and Getting His Wallet Stolen

Magnolia Pictures

“The Square is a sanctuary of trust and caring. Within it, we all share certain rights and obligations.” Those words, idealistic yet maddeningly vague, set the stage for Ruben Östlund’s The Square, an acidic comedy of manners that won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in May. Östlund’s central figure is Christian (Claes Bang), a Stockholm curator whose art-world cool cracks when his wallet and cellphone are stolen in a public place. Christian’s search for his property leads him into neighborhoods where his cultural cachet doesn’t apply—“I’m sort of a semi-public figure,” he wanly explains—and his attempt to smoke out the perpetrators leads to suspicion unfairly falling on a young boy, who obstreperously demands that Christian return and clear things up. At the same time, attempts to promote the museum’s newest installation, The Square, with an ill-advised viral video draw the wrong kind of publicity, and Christian has to juggle the crisis at work and a fling with a clingy American journalist (Elisabeth Moss).

In Östlund’s international breakthrough, Force Majeure, a father’s duty to protect his family paled in the face of his impulse for self-preservation, and The Square draws an even more pointed contrast between high-flown ideals and baser instincts, not least via a long and uncomfortable scene where guests at a black-tie dinner party are amused and then menaced by a performance artist all-too-convincingly mimicking a wild ape. (In Östlund’s imagination, the tuxedo-and-evening-gown crowd was Cannes’ jet set audience and the disruptive ape-man was The Square itself.) Although it was initially received as an art-world satire, the new movie has more sprawling aims: Imagine, if such a thing is possible, one of Michael Haneke’s exacting morality plays with a wicked sense of humor, or Roy Andersson’s ultra-deadpan tableaux minus the Scandinavian gloom.

I met with Östlund at the Manhattan offices of his U.S. distributor, Magnolia Pictures, where we talked about witnessing a bank robbery, the social contract, and why he loves YouTube so much.

Sam Adams: So I saw the movie at the New York Film Festival—

Ruben Östlund: Where my phone got stolen. And my wallet.

Tell me about that.

It was so funny, because what I had been doing is like, when I introduce the film, in order to show the trust for the audience in this city, I put my wallet and my cellphone in the screening room, and then I leave for the screening. And then when I come back for the Q&A, I’m like “Ah, it’s still here. Now let’s have the Q&A.” I’ve done this in Toronto, L.A., San Sebastian, in Stockholm. And then I did it at Lincoln Center in New York, and when I got back, my wallet is gone. My cellphone is still there. No, I think they took the cellphone also. They are gone. And I’m like, are you kidding me? Someone took it? And the people in the front row are starting to feel embarrassed. So they’re like, “Yeah, there was a lady in a red sweater that took it.” I’m supposed to hold the Q & A, and I’m having a little aggression during the whole thing.

Afterwards, when we’re finished with Q & A there’s this super sweet lady that comes up, and has collected dollars [from the audience] and wanted to give them to me because she felt so guilty. I have to say, no, no, no. I can’t take it. I can’t take it. And when I get out to the car, it turns out it’s the publicist that has taken the cellphone and the wallet, in order that no one else should take it. And I was like, do you realize that I was yelling at the whole audience?

That idea of collective responsibility figures heavily in the way you thought about The Square. You’ve told the story many times of how your father was sent out to play in the middle of Stockholm when he was 6 years old, with a sign around his neck to tell adults where he lived. Why is that story so important to you?

I think that it was a little bit how he talked about it. Back in the ’50s, we looked on the social contract in a different way. And I think that that story is interesting, also next to another story that a friend of mine told that is a journalist. He wanted to make a story about two phenomena going on in Sweden. One of the phenomena is the gated community, which if you look at it is a very aggressive way of saying, “Here’s the border of our responsibility. What’s outside of the gate we look at as a trap.” On the other side, in the poorer parts of the city, there’s groups that call themselves Mafia. And Mafia is a very aggressive way of saying, “We don’t accept the laws and rules of this society, we have our own laws and rules.” He was asking himself, what’s left in between? And how do we look on the common project of running a society? How do we look on our idea about the state, and so on?

So in this context, this idea of finding this symbolic place [The Square] came up. And I talked to a friend of mine who is a professor of sociology. He compares trust in a society to a coral reef. It can take quite a lot of damage, but there’s a tipping point when the consequences would be catastrophic. I think most of us feel powerless when we think about bigger problems in society. How do we change the attitudes in a society? How is it possible? But you know, in Sweden, we changed from left-hand traffic to right-hand traffic in one night in 1967. Isn’t that kind of amazing? “Actually, tomorrow we’ll start driving on the right side of the road.” Traffic rules are a very interesting comparison when it comes to changing a social contract. So of course we can create new social contracts, of course we can change the attitudes, and that is also something that is important to show to the next generation.

Magnolia Pictures

Christian is a father, but we don’t find that out until well into the film, after we’ve assumed he’s an enthusiastic middle-aged bachelor. Did you deliberately hold that information back from the audience?

When I was writing the script, first he was going to work, and he was saying goodbye to his kids, and this repeated. But at a certain point, I was starting to look at my own life: I was going to Cannes because I had a film in Un Certain Regard, and then I was going back and I had my kids. My life looks completely different the week when I have my kids. I love the idea that he is this guy out meeting women, and he’s single, and he has access to a certain kind of world in a certain way, and that when we would see that in the movie, then we would never expect him to be a father. But I know a lot of fathers who are like this in my life. So I love the idea that one day [his children] just come in into the apartment, and now it’s his week.

The Square is about the gap between the ideals we hold and the way we actually behave, and one of the places in life that’s most apparent is in raising children. Force Majeure is about that, too: The father knows he should stay and protect his family, but when his life is threatened, he just runs. Kids see what you do, not just what you say.

Exactly—and that is painful. That is also why I love that the boy is confronting him, you know? Like, “You’ve accused me of being a thief, you should apologize!” It’s scary when you know that the child is right and you are not. There’s something very scary about that as an adult.

You really zero in on the minute daily interactions that make up the fabric of a society. You’re in the elevator and you see someone coming: Do you hold the doors or do you let them close?

I love when the social contract is broken, and I love when there’s an agreement between people, which there is in almost every social situation. When that is broken, what happens then, or how do we deal with it? It’s a force majeure every time the social contract is broken. In order to live in the right way it takes knowledge and experience. I think that’s really why I love sociology. It’s a beautiful and topical subject. It’s daring to look at human beings when we fail.

The social contract can be misused, too. Christian thinks he’s coming to the aid of a woman who’s running away from an abusive man, but she’s just distracting him so her partner can pick his pockets. She’s exploiting his impulse to do good in order to rob him.

It’s a very civilized way of being uncivilized. Right before that, you have this crowdfunder that asks him, “Do you want to help out and save another human being’s life?” And then you’re supposed to sign something and give away some money. It’s practically the same thing, even though you’re doing it for the same cause. You’re putting guilt on the individual and—

You’re making them say, “No.”

Exactly.

“Do you want to save a human life.” “No, thanks.”

And then when someone is screaming “Help”—it’s interesting, that word, because it’s aiming at everybody, but it’s also pointing at you as an individual. I have a responsibility now. And if someone is misusing your willingness to help, that is something we’re constantly trying to judge, I think. When we see a beggar on the street, in which way is this beggar in need? Is he playing a role? Will I help this person’s situation at all if I give?

I think it’s interesting when you talk about the way beggars are portrayed in this film, because some people are very upset about it. I think that we want to look at poverty in a very sentimental way. We want the poor people to be in solidarity, at least with each other. But poverty is not creating solidarity. It’s creating a kind of mean behavior, actually. We don’t want to admit that, because I think it’s safer for us to sit in a certain middle-class, upper-middle-class, position, and look down on poverty and think, “At least they are more genuine than us in our materialistic world.” But poverty creates bad behavior.

We’re in the middle of a moment when profound questions are being raised about the kind of behavior that’s been permitted in the movie industry, and on a set, that atmosphere starts with the director. How do you deal with that responsibility?

One thing of being a director, you have these pressures on yourself that you have, daily shooting, and then you have to push the people that you’re working with, and you have to make them put in a lot of effort, and sometimes you have to be angry, because you don’t feel that you get the kind of effort that you want. So that is one thing. But when it comes to this kind of culture in the cinema world, the world of cinema has been dealing so much with female characters and the female body and sexuality. Sexuality and looks have become the value for female actresses. And if you look at the kind of content that we have in the movies, it’s over and over again a man harassing a woman, a man raping a woman. It’s violence between men towards women. Since I believe that the human being is an imitating creature, we are imitating what we are seeing. And we are not as rational as we want to be. We are also creating a certain kind of behavior with that content. But I think we have to also look at it from an animalistic perspective, that we are animals with instincts and needs that want to be civilized. There’s a clash between instinct and needs in our civilization and our culture, who we should be.

Magnolia Pictures

The scene with Terry Notary is very much about that. He plays a performance artist who invades a black-tie dinner party while acting like an ape, and as his behavior becomes more violent the guests go from being amused to genuinely frightened, and yet no one acts to stop it.

I wanted them to start as very sophisticated, and then end as wild animals themselves. The voiceover in the scene is very much trying to point out the bystander effect from the sociological and behavioristic perspective. What is the reason that we don’t act? And it’s because we are thinking, don’t take me, don’t take me. Take someone else. Right? It’s not that we don’t want to help; we are getting paralyzed because we are herd animals. For me, it is about that. I think it’s quite often with a scene that if you dare to go in a surrealistic way, it can become a metaphor for quite many things. I think that the really strong thing about cinema is that we are using the moving image, and the moving image has a fantastic way of showing human behavior. I don’t know if I talked about all the YouTube kids that I love—

You haven’t, but I know you love YouTube.

There’s one clip that I’ve been talking quite much about. It’s “Cab Driver on the BBC,” which I think points out who we are more than any feature film that I’ve seen the last ten years. [In the clip, a man waiting to interview for a job at the BBC was mistakenly interviewed on live TV as an expert in trademark law.] We are trying to live up to the expectations of the role that we should play, even though if we don’t have any coverage. In order to not lose face, we are willing to go very far, on very thin ice.

The movie starts off with Christian being interviewed by an anxious journalist, played by Elisabeth Moss, who asks him to explain a statement that a museum show focuses on "the topos of exhibition/non-exhibition.” I gather you borrowed that statement from a colleague at the university where you teach.

I stole it. I haven’t asked for permission yet. I wanted the power to shift in that scene. You have the feeling that he is a person that is high status in comparison to her, and then he suddenly should be pushed into a corner with this completely absurd art-theory bullshit—where, if you scratch the surface, it’s basically nothing on the inside.

So does your colleague know you put that in the film?

I haven’t asked him. I met him in the corridors of the university, and I said hello like nothing ever happened. In that interview situation, I love looking at—I don’t know if you remember when the president of Iceland was pushed into a corner because he had some bank accounts in Panama or something like that.

It rings a bell.

The moment when someone is sitting in front of a journalist and doesn’t know how to handle the situation, it’s spot-on the fear of being a human being. Not having coverage for who we say that we are. So I think that I wanted to put Christian in that corner.

You talked about the bystander effect, and that’s something you have first-hand experience with. Your short film Incident by a Bank is about a bank robbery you witnessed, and where you—

Were the bystander. Sure. But that was also so interesting, I think, because the reason that I wanted to shoot that in a real-time shot was because when I experienced it, it fit in so badly with the fiction references that I had in my head. I thought I knew what a robbery attempt would look like. Where did I get that preconception? Where did that come from? And then I realized that the only time I have experienced this is in the movies. There were so many details in it that were trivial, and romantic, and funny, and absurd at the same time. How strange, you know? Do you know something fun about that?

No, go on.

Like a year after it was released or something, then I got a link from a friend that had been watching an American TV show that is called The Top Ten Dumbest Criminals in the World. And in place number seven, there is the material from one of the extras that have been filming the [recreated] robbery, and now they are saying, this is an authentic material. And they are making up, like, “The robbers got away with a small fortune.” You know? What the fuck?

That’s incredible.

So that was kind of absurd, without feeling shame at all, pretending that this is the authentic material.

Lack of shame seems like a good place to end.

Yeah, that’s the problem with me. Lack of shame.