When Someone Else Writes Your Memoir

One of the lessons a writer should learn early is that the allure of the personal forms—memoir, autobiography, personal essay, etc.—should be regarded with suspicion. These genres seem to promise a high degree of expressive freedom, but they actually require the most writerly care imaginable. The “I” isn’t really the author on the page; it’s a carefully constructed persona, a golem sculpted and animated to make universal meaning out of otherwise, for the most part, uninteresting material.

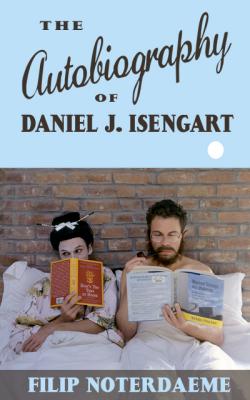

But how far can such artifice go before the book becomes something other than personal? In his recently released and curiously titled memoir, The Autobiography of Daniel J. Isengart, Filip Noterdaeme set out to test the limits of the form. A conceptual artist by trade, when Noterdaeme decided to write about his gadfly-like place in the contemporary art world—he’s best known for The Homeless Museum of Art—a typical memoir didn’t seem quite right. “I am wary of the autobiography genre,” Noterdaeme wrote in an email, “its seriousness, its tendency to be earnest, its hapless, inherent aim to be convincing and gain the reader’s sympathy.” Indeed, even using a normal “I,” no matter how well-wrought, failed to entice. So Noterdaeme chose to draw on Gertrude Stein—specifically, her acclaimed The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas—as a model.

In Stein’s book, she assumes the guise and clipped syntax of Toklas, her lover, to describe their lives and social circle up until 1933. Noterdaeme similarly writes from the point-of-view of his partner, the German cabaret performer and personal chef Daniel Isengart, on parallel themes—but further complicates the maneuver by maintaining Toklas’ sound. In other words, Noterdaeme transforms his own story in both perspective and style; the resulting “ménage a quatre,” as he calls it, produces a weirdly plural “I,” with Noterdaeme channeling Stein parroting Toklas, all through the mouth of Isengart.

While organizing so many voices in a single head would seem, well, crazy-making, Noterdaeme did not attempt such a strange exercise just for thrills. For one thing, it gave him a chance to try out what he calls “autotranslation,” a technique of “linguistic distancing” that he sees in writers like Stein and Paul Célan that ultimately yields “a more universal level of meaning”—something sadly missing in many of today’s glut of memoirs.

And with distance also comes a certain amount of puckish freedom. Noterdaeme found that the technique gave him greater license to make “bold statements” about the art world, his own work, and “some pretty famous people,” he said. That predilection for gossip is another thing Noterdaeme shares with Stein; the latter, in her book, treats us to dryly delivered dish on Picasso, Hemingway, and others who frequented her home. In one memorable moment from Daniel J. Isengart, the narrator recalls a particularly inelegant run-in with etiquette maven Philip Galanes, later hired by the New York Times. While Isengart is cooking at a posh Hamptons home, he overhears a young couple ask Galanes where they should send their young son to school; he opines that they shouldn’t “send him to a local public school, what good could possibly come from your son growing up with children from poor families, surely he will never have anything to do with them later in his life.”

Noterdaeme insists such juicy bits, which feature society people and museum directors and downtown artist types, were not included haphazardly. After getting down Stein’s style, the next challenge for him and Isengart “was finding stories and characters in Stein’s book that would ‘fit’ our stories and the people in our lives,” so that they “could filter them through hers,” sometimes, phrase for phrase. (When recalling how she first met Stein, Toklas notes that she “was impressed by the coral brooch she wore,” while Isengart, meeting Noterdaeme, “was impressed by his tight white T-shirt.”)

Both narrators, Toklas and Isengart, then say that their new acquaintances—Stein and Noterdaeme, respectively—are clearly, upon first glance, one of the three true geniuses they have met in their lives. A touch narcissistic perhaps, considering the actual authors behind those words. But then, given Noterdaeme’s self-effacing daisy-chain of “translation,” I'm willing to allow the autobiographer a bit of autoeroticism.