Meet One of the Moon’s Youngest Craters!

On March 17, 2013, something hit the Moon. Hard.

Most likely it was a small rock, probably about the size of a basketball. However, it was moving at interplanetary speeds, much faster than a rifle bullet. Its energy of motion was converted into light, heat, and rapidly expanding debris.

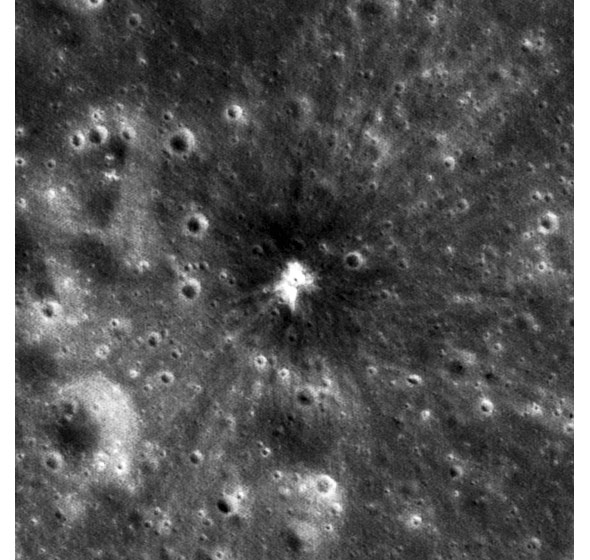

When all was said and done, it left a crater about 18 meters (60 feet) across on the lunar surface. From its vantage point just a few dozen kilometers above the Moon, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter was able to capture images of the crater—shown at the top of this post—as well as the same region from before the asteroid hit:

Photo by NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

The field of view is about 500 meters (0.3 miles) across. As you can see, the crater itself is small, but its influence large; debris excavated by the sudden release of energy flew for hundreds of meters.

You can tell the crater is young (well, besides it not being in the picture from February 2012) due to the well defined “ejecta blanket,” the skirt of material around it. As craters age, exposure to solar wind and the constant rain of micrometeorites wears the ejected matter down, fading it.

The Moon is hit by cosmic debris all the time, but this is the largest explosion on its surface that we’ve actually seen. The beauty of this is that the explosion itself was well-monitored, and now we have images of the crater as well. That means the size of the crater and the amount of excavated material can be tied to the size of the impact event itself, a crucial piece of the scientific puzzle. The physics of hypervelocity impacts is complex, and experiments on Earth don’t usually generate impact speeds this high—the asteroid was probably moving at 25 kilometers per second (55,000 mph) when it hit! Being able to get observations before, during, and after the impact is a wonderful opportunity to understand these events better.

In fact, this can help everyone understand these better: NASA has a fun educational activity about impact craters available for free; if you're a teacher you should really take a look. This is a great opportunity to bring a real event into the classroom and get your students excited about astronomy. Not too surprisingly, I think this is A Good Idea.

Tip o' the No. 2 pencil to NASANEOCam for the link to the activity.