“Mr. Thursday”

A new short story from Station Eleven author Emily St. John Mandel.

Lisa Larson-Walker

This short story was commissioned and edited jointly by Future Tense—a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate—and ASU’s Center for Science and the Imagination. It is the second in Future Tense Fiction, a series of short stories from Future Tense and CSI about how technology and science will change our lives. The first installment was “Mika Model,” by Paolo Bacigalupi.

1.

A strange incident in October:

Victor returned to the showroom for the fourth time in two weeks, after hours. He just wanted to look at the Lamborghini through the glass. He was stalking the car, if he was being honest with himself. He’d taken it on two test drives, memorized the technical specifications, gazed at photos of it in online galleries, read reviews by the lucky professionals who drive fast cars for a living. He’d told himself that if he still loved the car a week after the second test drive, he would do it, he’d commit, he’d stop obsessing and write the check, and the car would be his. Victor made what seemed to him to be an obscenely high income. He had no debt, no dependents, owned his home outright, had paid off his parents’ mortgage, and lived well below his means. He wanted the car.

It was a clear night, unseasonably warm, and Victor was all but alone on the street. The Aventador SV Coupé had its own spotlight on the showroom floor, but it seemed to Victor that it almost emitted its own light. It was a brilliant yellow. He loved it.

Victor was so enchanted by the car that he didn’t notice the man approaching on the sidewalk.

“You’re admiring the car,” the man said. He had a slight accent that Victor couldn’t place. He was about Victor’s age, early 30s, wearing a midrange beige suit and a gray trench coat. The coat’s shoulders were wet, as if the man had just walked through a rainstorm, but to the best of Victor’s knowledge, the sky had been clear all day.

“Do I know you?” Victor asked. “We’ve met, right? You look familiar.”

“Listen,” the man said, “I don’t have a lot of time. I’ll give you $10,000 if you don’t buy that car.”

Victor blinked. The strangeness of the offer aside, he was a man for whom $10,000 wasn’t a particularly impressive sum of money.

“There’s a lot at stake,” the man said. “I wish I could tell you.” He had a fervor about him that made Victor a little nervous. Victor was certain he’d seen him before but couldn’t place him.

“Why would you pay me …?”

“I don’t have much time,” the man said. “Do we have a deal?” and Victor knew he should be kind—it was clear to him by now that the man wasn’t well—but it was 10 p.m. and he hadn’t had dinner yet, he’d been working 100-hour weeks, and he was just so tired, the workload was relentless, lately he’d started to wonder if he even actually enjoyed being a lawyer or if his entire life was possibly a ghastly mistake, and now this lunatic on the sidewalk was trying to get between Victor and his beautiful car.

“I know it’s strange,” the man was saying, with rising desperation. “I’m risking my job being here and talking to you like this, but if you would please, please just consider—” but the car was Victor’s joy and his solace, so he turned and walked away without saying another word. He glanced over his shoulder a block later and the man had disappeared, the empty sidewalk awash in the showroom’s white light. Victor bought the car the following morning, and had more or less forgotten the encounter by the end of the week.

2.

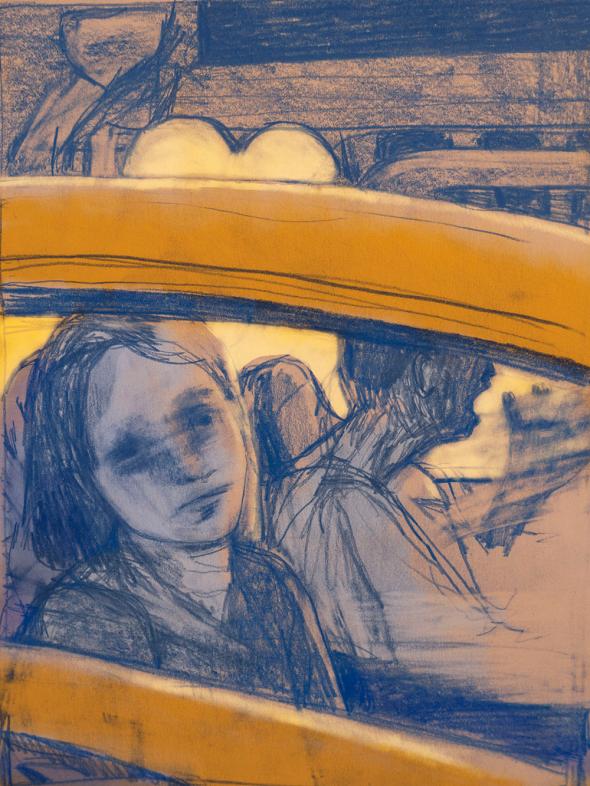

Lisa Larson-Walker

Three weeks later, at 2 a.m. on a Thursday in November, Rose sat up gasping in her bed. The details were already fading as she switched on the light, but she was certain it was the same nightmare that had woken her the previous two nights: an impression of noise and chaos and then behind that something silent and overwhelming, a kind of cloud, a borderless rapidly approaching thing that wanted to engulf her. There were tears on her face. Rose knew from previous nights that further sleep was impossible, so she showered and dressed and caught the 4:35 train.

The others on the train at that hour were mostly financial-industry maniacs, eyes bright in the shine of their tablets and laptops and phones, sending and receiving messages from Europe, where their counterparts were drinking second cups of coffee and starting to think about lunch, and Asia, where late afternoon shadows were lengthening over the streets. Rose took a seat by the window in an empty row, rested her forehead on the glass, and drifted into a twilight state that wasn’t sleep and wasn’t consciousness, towns appearing and receding between intervals of trees. When had she last been so tired? Rose felt slightly delirious, her heart beating too quickly, thoughts clouded. She wished she could remember the specifics of the dream. She woke with a start as the train pulled into Grand Central, stepped out onto the filthy platform, and made her way with the others up into the cathedral of the main concourse, still quiet at this hour. On the downtown subway she sat with her eyes closed, trying to gather herself, until the train reached the southern tip of the island and she climbed the stairs into cool air and morning light.

Rose had started work at Gattler Fitzpatrick six months earlier, which is to say two months after her husband had been remanded into custody. The firm—three attorneys, a paralegal, and now Rose—occupied a shared office space just off Wall Street. On the 14th floor of a glass tower, a rotating cast of companies leased various combinations of cubicles, offices with views of other towers, and offices with views of the cubicles. Gattler Fitzpatrick had one of the more expensive suites: three offices and a reception desk in a secluded corner. When Rose arrived for her job interview, she turned a corner to walk down a silent row of cubicles and found it unexpectedly populated, people typing or talking on their phones, audible only when she was almost upon them, row upon row in their little gray squares.

Rose had worried about the gap in her résumé, the abyss of five years between the executive assistant position in Midtown and the present moment, but the truth proved surprisingly adaptable: She had been married for some time to a man with money, she explained to Jared Gattler in the job interview—his gaze flickered to her ringless left hand—and she’d stopped working at his invitation, but now they were separated and she wanted to be self-sufficient. All of this was perfectly true. Gattler didn’t need to know that they’d been separated by the federal prison system.

Gattler was in his mid-70s, shorter than Rose, with a feverish complexion and the fatalism of people whose professional lives are played out in divorce court.

“Half my clients,” he said, “the women, I mean, they’re divorcing guys who don’t actually make much money. Small players. I’m talking guys who can barely support one household at the level to which these people are accustomed, let alone two.” Rose nodded, interested. “My clients, they’re not idiots per se, but they just can’t get it through their pretty little heads that the situation’s changed. They just can’t absorb the fantastical notion that they’re going to have to be on the 7:40 a.m. train to the city just like everyone else. They just want to putter around town doing whatever it is they do, getting their hair done, going for lunch, whatever. I’m not sexist, you understand.”

“Of course not.” Their pretty little heads, Rose thought. In the fantasy version of that moment she rose with quiet dignity, walked out of the office without saying another word, and met her husband for drinks to commiserate.

“I’m just talking about a lack of connection to reality,” Gattler said. “Nothing to do with gender per se, not saying anyone’s less intelligent. All I’m saying is some of my clients, these are people who live in a fantasy world where they’ve never had to be adults.”

“An entitlement issue,” Rose said, because she was down to her last $200 and couldn’t afford to walk out of this or any other office. From the way Gattler’s eyes brightened, she knew the job was hers.

“Exactly,” he said, “that’s exactly it. Whereas I look at you, it seems to me you’re showing a little initiative here.”

“Well, I’ve never wanted to be dependent on anyone else,” Rose said. This was only theoretically true. If she’d never wanted to be dependent on anyone else, then how had it happened so easily? On the train back to Westchester County, she’d stared out the window at the suburbs and the summer trees, and of course the answer was depressingly obvious: She had slipped into dependency because dependency was easier. She’d worked so hard all her life, and when her husband had extended a raft, it was easier to stop swimming and float. Where was Daniel at this moment? She imagined him waiting in a cafeteria lineup, reading in his cell, doing pushups in a sunlit yard. Westchester was a blur of green. Rose played the game she’d been playing since childhood: You look at the surface of the passing woods, the screen of trees, then you adjust your eyes to look past the screen and into the interior, where sunlight catches on tree branches and leaves shine translucent in the shadows, and it’s like seeing an entirely different place. The interior of the kingdom versus the castle wall.

At Gattler Fitzpatrick, Rose did the filing, handled scheduling for Gattler and another attorney, straightened up the little waiting room between clients, maintained a vase of fresh flowers on the reception desk. At 5 o’clock every day, she joined the evening crowd flowing north to Grand Central Terminal. She bought a prepared meal for dinner in the market and boarded a MetroNorth train back to Scarsdale, where she was renting an au pair’s suite above a garage within walking distance of the train station. She heated her dinner in the microwave and ate alone, read the news and watched television for a while, went to bed early, rose and returned to work earlier than she needed to the next day. It was possible to imagine years slipping past like this, decades, and there was comfort in the thought.

There was nothing Rose wanted more than a predictable life. When she arrived at work and stepped off the elevators, she always walked through the cubicles instead of going around, because they reminded her of a maze on the grounds of a particular castle in England that she’d visited with Daniel in her former life.

On that Thursday morning in November, the cubicle maze was empty—it wasn’t yet 7 a.m.—and Rose took a circuitous route, enjoying the silence. In the quiet and order of the 14th floor, the nightmare that had woken her seemed very distant. The morning passed without incident—filing, coffee, phone calls, scheduling, a salad and too-sweet iced tea for lunch—and then the long afternoon stretched before her. More filing, a weepy client in the waiting area, a gale of laughter from a conference room around 2 p.m., more coffee, a bright blue ring on the finger of a woman who pressed the button on the elevator on the way back up from Starbucks, a flash of pink socks beneath the gray suit of a worker in the cubicles, a moment of dull stupid panic when she thought she’d lost a file. She moved through the day with a feeling of floating, a little undone from too much caffeine and too little sleep, light-headed, heart pounding, cup after cup of coffee that left her with something that wasn’t exactly a headache, more like a pulsing suggestion of phantom lights in the periphery of her vision, her hands trembling a little. At 4 o’clock, Mr. Thursday arrived.

Rose didn’t know his name. Gattler wasn’t the kind of man who appreciated unnecessary inquiries, and his calendar provided no clues. The entry, which had been set up to recur every Thursday until the end of time, read “Thursday mtg” and nothing else. Mr. Thursday was more or less Rose’s age, somewhere in his early 30s, a thin man in an aggressively nondescript beige suit who emerged from the cubicle labyrinth at precisely 4 o’clock every Thursday, nodded politely on his way past her desk, and disappeared into Gattler’s office.

Lisa Larson-Walker

Was there something unusual in the way Mr. Thursday glanced at her that afternoon? He nodded, as always, an unhappy aspect to his expression, and it seemed to her that he held her gaze a beat too long, which led Rose to suspect that perhaps the sleep deprivation was making her look worse than she’d thought. She confirmed this suspicion in the ladies’ room mirror: dark circles under her eyes, a fixed and somewhat glassy quality to her stare. She had recently reached the age when sleep deprivation made her look not just tired, but slightly older. Mr. Thursday was still in Gattler’s office when she left at 5 o’clock.

It was raining by then. She had no umbrella, but there was a certain pleasure in this. She liked the sharp, cold of rain on her uncovered head. By the time she reached the stairs of Bowling Green Station, the dull wasteland of the day had somewhat dissipated, burned off by the cold and rain and lights, the evening acquiring a certain momentum. An uptown train was arriving just as she reached the platform, and she stepped aboard with the feeling of being involved in some pleasant choreography, but then the train reached Union Square, and all momentum came to a halt. The doors opened but didn’t close. The train didn’t leave the station. The car filled up, a crush of commuters who closed their eyes to concentrate on their music, or stared or at their phones or at books, or stared at nothing. The announcement came after five or 10 minutes: train going out of service, everyone please exit. There was no further explanation. The passengers shuffled out onto the already crowded platform, some muttering curses but most closed up in a resigned or furious silence.

The sleep deprivation had made her mildly deranged, Rose decided, and that was why this moment felt like déjà vu. She’d been here before, hadn’t she? Here, in this moment, exiting this train? The woman beside her wore a beautiful blue wool coat, and Rose was certain that she’d seen this coat before, but not somewhere else: She’d seen the coat before in this moment, exiting this train, here. Every face in the crowd looked somehow familiar. She was dizzy. The train doors closed behind the last of the passengers, and the cars stood empty and alight. The crowd swelled dangerously on the platform, a mass of damp coats and hot, stale breath and tinny music from headphones, scents of hairspray, coffee, cologne, a McDonald’s bag, a cloying jasmine perfume that made Rose want to gag. The out-of-service train didn’t move, and no trains arrived on the opposite platform. Rose had never liked crowds, and it seemed to her that if she didn’t get out of the subway she might faint in the crush, so she began inching her way toward the stairs in a series of tiny half-steps, excusing herself again and again. It was difficult to get enough air. Rose couldn’t shake the terrible sense of following a script, of being an actor in a movie she’d already seen. She fought her way up the final staircase out of the station and emerged gasping into the evening air.

The rain was a drizzle that blunted the streetlights, Union Square lit gently, puddles reflecting. Her relief at being away from the crowd was overwhelming. What now? She sat on the nearest bench to consider her next move. At this hour of the day the city was in motion, umbrellas crossing Broadway like a flock of dark birds.

“Tiffany?”

It was Victor Freeman, the youngest member of her husband’s legal team. Their offices were near here, she remembered. He stood over her with an umbrella.

“I don’t use that name anymore.”

“What can I call you?”

“Rose.”

“Pretty.” He sat beside her, although the bench was very wet, and angled his umbrella so that it sheltered both of them. His overcoat looked warm and expensive, the opposite of Mr. Thursday’s cheap beige. “Why are you sitting out here in the rain?”

I was waiting for you, she thought, but of course this didn’t make sense. “The subway’s down,” she said. “I came up for air.”

“Where were you headed?”

“Home. Scarsdale.”

He frowned, confused. Rose and Daniel’s house in Scarsdale had been seized along with all of their other assets.

“I rent an au pair suite. It’s a room with a kitchenette and a bathroom over a garage.”

“Oh.”

“I like it. It’s all I need.”

“Let me give you a ride home. My car’s in a garage around the corner.”

“You live in Scarsdale too?”

“No, but as a former member of your husband’s defense team, I feel that driving you home is literally the least I can do.”

“How far out of your way is it?”

“Professional guilt notwithstanding,” he said, as they walked in the direction of the garage, “I just bought a car, and to be honest, I’ll take any opportunity to go on an unnecessary drive.”

The yellow Lamborghini seemed to shine in the dim light of the garage.

“It’s a ridiculous car,” Victor said, “but I love it.”

“I don’t think it’s ridiculous.” Rose thought it was beautiful, and when she said this, Victor smiled.

“I think it’s beautiful too, actually. It’s like something from the future. I know it’s a frivolous purchase, but I don’t know, I just wanted it so much.” The déjà vu was surfacing again, nudging against the surface of the evening. “I agonized for weeks,” Victor was saying, “but if there’s a thing you really want, and you can afford it, and it’s a beautiful thing that genuinely makes you happy, is there actually anything wrong with just buying it? You could call it crass materialism, but life’s so short.” It seemed to Rose as she buckled herself in that there was something familiar about the car, but she didn’t recognize it for another 47 minutes, when the accident began: the SUV drifting into their lane just as Victor turned to ask her something, the delivery truck behind them that didn’t stop in time. She didn’t recognize Victor’s car until the moment of impact, the blare of horns: She knew this car from the nightmare that had woken her three nights in a row. She remembered now. In the dream, and now in waking life, time slowed and expanded. The car was turning sideways between the delivery truck and the SUV, the air filling with glass, steel crumpling, and the thing from the dream was rushing toward her, the overwhelming thing that was dark and quiet and could not be resisted; this was the thing that had jolted her out of sleep when she dreamed it, but in waking life it turned out not to be terrifying at all, only inevitable; it was catching her in the crush of steel and plucking her gently from the accident, it was sweeping her up.

Lisa Larson-Walker

3.

Three-hundred and forty years after the accident, a lounge singer was drinking scotch with a businessman in a spaceport terminal bar. They’d been flirting half-heartedly for 15 minutes or so. “And you,” the businessman was saying, “where are you off to today?”

“I’m going to the moon,” the singer said. The businessman raised his glass. The bartender appeared with a bottle.

“Oh, no, I was just toasting her,” the businessman explained. “She’s going to the moon.”

“Everyone here’s going to the moon,” the bartender said. “The next Mars flight isn’t till tomorrow.”

“Still,” the businessman said mildly, “always worth toasting a change of scenery.” The singer smiled at him and sipped her scotch. “Which colony?” the businessman asked.

“I’m headed up to Colony Two,” the singer said. “I got a job in a hotel. Actually in a chain of hotels.”

“Hilton?”

“No, Grand Luna.”

“Ah, I’ve stayed at the Grand Luna. Nice place. Did you tell me you’re a singer?”

“I did. I am.”

“My daughter likes to sing,” the businessman said. He looked a little awkward following this announcement. The singer didn’t strike him as the sort of person who enjoyed discussing children. He motioned to the bartender for another glass, but the bartender had developed a sudden interest in the projection above the bar, which was showing a baseball game.

“Can I ask?” the singer asked, with a gesture that encompassed the businessman’s outfit. He was wearing a beige suit in a style that hadn’t been fashionable since the early 21st century. The shoulders of his overcoat were still damp with 21st-century rain.

“It’s for my work. Well, was for my work, I guess I should say.”

“You’re one of those.”

“Was one of those. Until this morning.” The businessman raised his glass, which by now contained only a pair of rapidly melting ice cubes. “To getting fired.”

“Oh. I’m sorry.”

“I’m not. It’s a creepy line of work, frankly.”

“It always seemed dangerous to me. Going back like that.”

“Dangerous and stupid,” the businessman agreed. “Happy to be out of it. My prediction, it’ll be illegal by next year.”

“I mean, what’s to stop an accident?” the singer said. “Even the smallest thing, you know, you walk through a door ahead of someone … ”

“You wouldn’t believe how many meetings I’ve sat through on this topic.”

“So you walk through a door in front of someone else, and then, I don’t know, say that little delay means he doesn’t get hit by a car, and he goes on to cause a war that wipes out all of our great-grandparents.”

“If not all of humanity,” the businessman agreed. He was trying to flag down the bartender, who was absorbed in the game. “This is actually why I drink, if you were curious.”

“And in that case it’s not that we die, exactly, you and I and everyone we love.” The singer gave what seemed to the businessman to be a somewhat exaggerated shudder. “It’s more that we never get to start existing.”

“The thought’s occurred to me.”

“Then why did you do it?”

“Same reason anyone does anything in business.”

“I’ll drink to that. When you went back,” she said, “where exactly did you go?”

“I specialized in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.”

“What were you doing there?”

He succeeded in getting the bartender’s attention and fell silent for a moment while the bartender refilled their drinks. He took a long swallow and glanced at the baseball game; the bartender had rotated the projection for a better view of a replay, and now there was a holographic outfielder directly over the bar. “Nothing sinister,” the businessman said finally, when he saw that the singer was still watching him. “Genealogical research for high net-worth individuals. Look, I’m not saying it’s safe. But if it makes you feel better, it’s not a free-for-all. There are controls in place, both technological and human.”

“Human?”

“I was required to meet weekly with a handler in the local time.”

“Kind of a weak control,” the singer said.

“Well, you might be right about that. It was the technological controls that got me fired.”

“Why’d you get fired?”

“I tried to avert a car accident.”

The singer was quiet, watching him.

“I didn’t think the scanners would pick it up. I knew it was stupid, but it’s not like I tried to avert the First World War.” The singer frowned. Her grasp of 20th-century history was shaky. “No matter what I did,” he said, “everything I tried, she still got in the car, and the car still crashed.”

“Who’s she?”

“Just someone I saw every time I went back. My handler’s secretary. I liked her. Kind of a sad story.”

The singer liked sad stories. She waited.

“OK,” the businessman said. By now he’d had a little too much to drink. “So this person, the secretary, she grows up with nothing, terrible family, meets a guy with money, falls in love with him, and then a few years later he goes to jail for some white-collar thing. Long sentence, judge wanted to make an example of him. All of his assets were seized, so she’s lost everything. She tries to—no, that’s the wrong word, she succeeds in starting a new life. Changes her name, gets a new job, picks herself up.”

“And then?”

“And then she dies six months later in a car crash. I don’t know, I guess I’d been in the business for too long. Maybe I got a little burned out. I was always so careful. I filed these impeccable itineraries with Control and never deviated from them, never tried to change anything, but this person, Rose, she looked a bit like my daughter, and I just thought, what harm would there be, making this one change? Averting this one thing? Most people don’t amount to much. Most people don’t change the world. If she doesn’t die in a car accident, what harm is there in that, really?”

“Isn’t that exactly the kind of small thing—”

“Imagine walking into a room,” he said, “and knowing what’s going to happen to everyone in it, because you looked up their birth and death records the night before.”

The singer seemed to be searching for something to say to this but failed. She downed the last of her scotch.

“I’m sorry. It’s an unsettling topic. I didn’t mean to make you uncomfortable.”

“My shuttle’s probably boarding by now.”

“You see the temptation, though? How you might want to just make this one small change, give someone a chance, maybe just—”

“ ‘Genealogical research for high net-worth individuals,’ ” the singer said. “You must think I’m an idiot.”

“I don’t.”

“Anyway, thanks for the drinks.” The singer was sliding carefully from her bar stool.

“You’re welcome,” said the businessman, who hadn’t realized he was paying. He watched her walk away and then touched one of the buttons on his shirt, which he’d kept angled toward her. The recording stopped.

“Fucking creep,” the bartender muttered, under his breath. The businessman settled up and left without looking at him.

Later, in his hotel room in Colony One, he dropped the button into a projector and played the conversation back. A three-dimensional hologram of the singer hovered over the side table. I’m going to the moon. A touch of excitement in her voice. In the background, the shadowy figure of the bartender polished a glass while he watched the baseball game. The businessman turned the volume to low. He liked to keep a recording going in the background when he was alone in hotel rooms, so as not to get too lonely. But this was the wrong hologram, he didn’t like the way the bartender hovered, so he scrolled through the library and picked out another: Rose at her desk in the 21st century, her smile when she looked up and saw him. He adjusted the speed to the lowest possible setting. The walk past her desk took only two minutes, but in slow motion there was such stillness, such beauty in her small, precise actions—as though underwater she turned from her keyboard to look at him, then back to her keyboard, her hand reaching for a file and bringing it with heartbreaking slowness down to the desk, and all the while he was gliding past her, on his way to Gattler’s office—and this seemed the right recording for the moment. He changed into his pajamas, switched off the bedside lamp so that the only light was the pale glow of the hologram by the bed. He stood for a moment by the window while he brushed his teeth. The hotel was expensive and looked out over a park, and it occurred to him for the thousandth time that if he hadn’t spent time on Earth, he might not know the difference. Tomorrow he’d board the first train to Colony Three, go home and tell his wife what had happened, sweep their little daughter up into his arms. Would his wife be angry? He thought she’d understand. They’d talked about getting out of the industry. But for now he was alone in the quiet of the room. He would never return to the 21st century, and there was a sense of liberation in this. He could find a new job. He could live a different, less haunted kind of life. In the silence of the room, the hologram of Rose was reflected on the window, turning in slow motion away from him, superimposed on the pine trees and tall grass of the park. An owl passed silently between the trees.