Though rarely read, terms and conditions agreements are the secret master texts of our modern technological age, underpinning nearly everything we do even as we casually click past them. If you’re like me, you don’t even bother scrolling to the bottom of an end-user license agreement unless forced to. Who could fault us for our incautious nonchalance? As Seth Stevenson wrote in Slate last year, it would take a month just to make sense of all the terms and conditions we face in one year.

With iTunes Terms and Conditions: The Graphic Novel, artist R. Sikoryak aims to achieve the impossible: to make us read a document that virtually all of us have willfully ignored. Sikoryak’s recently completed book, published serially on Tumblr, contains the entirety of Apple’s iTunes terms of service, spreading its 20,000-odd words out over 94 pages, each styled after the work of a different comics artist. On a page that echoes a famous spread from Watchmen, a woman throws an iPhone through an incorporeal Steve Jobs as he lectures her about passwords and authentication procedures. On another, a Jobs who could have been drawn by cartoonist Jim Davis talks privacy protections with a computer that bears a striking resemblance to Garfield.

Despite its absurdist qualities, the book is surprisingly readable. Sikoryak has a long history adapting classic literary texts as if they’d been drawn by other comics artists, reimagining Dante’s Inferno in the style of Bazooka Joe, Wuthering Heights as a Tales From the Crypt story, and more—parodies that exhibit clear love for both their source material and the history of comics.

The source material for Terms and Conditions is, to put it mildly, less literary. Sikoryak found this to be both a challenge and an inspiration. “The text is anti-narrative,” he told me. “It doesn’t lend itself to illustration.” (Though to be fair, formal agreements have long relied on typographical cues like block capitalization, a tactic familiar to readers of comics.) By breaking the dense legalistic language up and inserting it into classic comics pages, Sikoryak sought to appropriate the visual medium’s narrative drive, creating the implication of story where none exists.

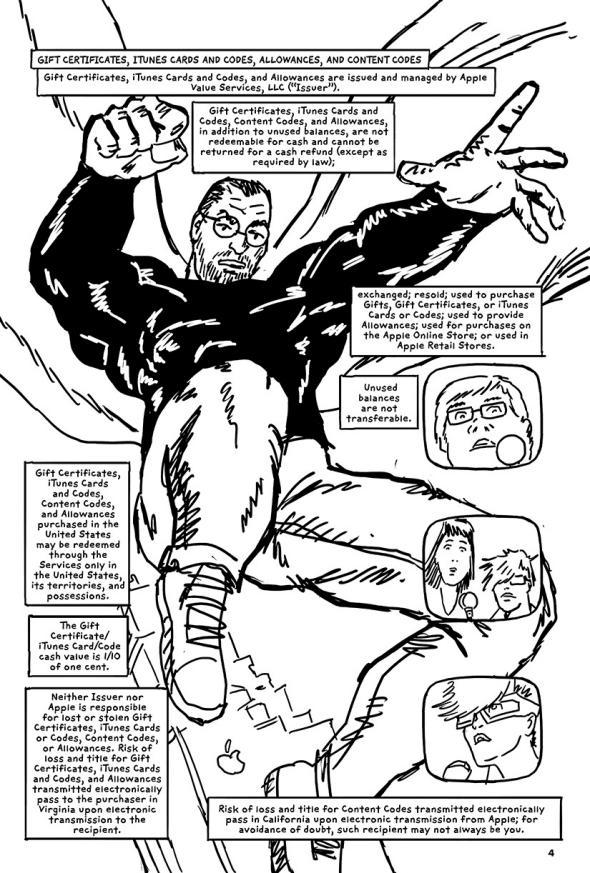

Sikoryak also had help in the form of an obvious natural protagonist for his tale. Steve Jobs appears in virtually every panel, leading the reader—and sometimes other characters—through the intricacies of the agreement. Sikoryak sketches an always shifting parade of Steve Jobses, sometimes presenting him as a cosmic superhero, sometimes as a Transformer, and once even as Homer Simpson. But through it all, every Steve Jobs is still his iconic self—turtlenecked, bespectacled, and sporting a beard—providing continuity as Sikoryak moves from one style to the next and smoothing over transitions that might otherwise be jarring.

For all that, there are some deeply weird, sometimes revelatory moments within the book’s pages, moments that would be difficult to notice without Sikoryak’s approach, let alone to reach in the first place. Sikoryak claims that for the most part he drew the pages before choosing what sections of the document he would incorporate into them. “The decisions … had as much to do with the real estate in the word balloons as anything else,” he said, telling me that the connections were often a matter of structural serendipity.

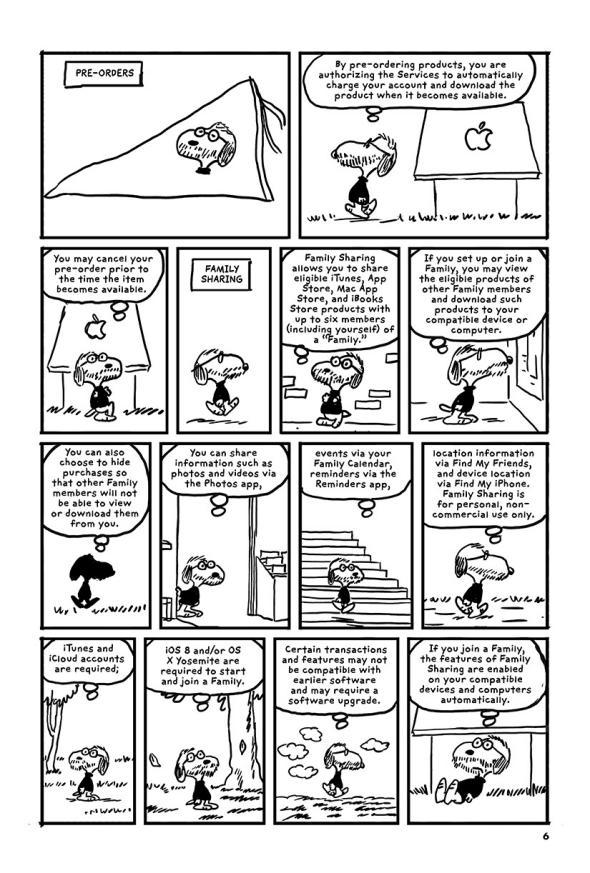

The word-image pairings are frequently apt. An early page done in the style of Charles Schulz (with Snoopy in the Jobs role) finds Apple explicating the word family in surprisingly nontraditional terms, suggesting it might have more to do with chosen bonds than biological ones. It’s a simple enough idea meant to allow Apple to define the scope of content sharing, but one that leads to phrases such as, “iOS 8 and/or OS X Yosemite are required to start and join a Family.” The strangeness of this detail might not resonate so clearly were it not for our existing associations with the similar peculiarities of kinship in Peanuts.

Courtesy of R. Sikoryak

Sikoryak stumbled across other oddities while working on the project—in Apple’s documents as well as the original comics he references throughout. “There’s this whole thing in there about terrorism and not creating weapons out of the things you discover,” he said, pointing out some of the more absurd terms and conditions. Meanwhile, he realized as he worked that many of his pages featured the various Jobses fighting with women, sometimes in a strikingly mansplain-y spirit. Sikoryak wasn’t, he told me, trying to make some point about Jobs, suggesting instead that it was probably a consequence of the “male-driven” qualities of many of the older comics he was referencing.

Significantly, though, Sikoryak’s book isn’t just about older comics. It also draws on an array of works by a wide range of creators, male and female, mainstream and indie, print and Web. Indeed, even if it ultimately teaches you nothing new about what Apple wants from you, Terms and Conditions still provides an admirable, and delightfully idiosyncratic, survey of the existing diversity in the comics medium—stylistic, thematic, and cultural.

This, ultimately, may be what the average reader takes away from Sikoryak’s labor of love. There just aren’t many broader lessons to be taken from making your way through the iTunes terms and conditions. There’s no sinister secret here, no evil pattern or hidden logic. “A lot of people assume that there’s something malicious in making them so long, that they’re trying to prevent you from reading them,” Sikoryak said. “But I think it’s just lawyers trying to cover [the company’s] asses.”

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.