We all have quiet nights at home where we sit with a cup of tea and go through the Terms of Service agreements for the software and websites we use. Right? OK, yeah, no. But even if you’ve never read a ToS in your life, you do know one thing about them: They basically always include sections that are in all caps. BUT WHY?

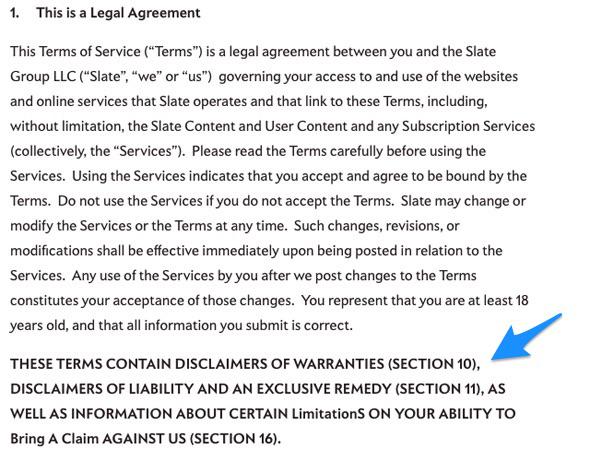

It all starts with the idea of “conspicuous” text—using formatting or typography to call attention to certain parts of a legal document so they’re harder to miss. Many laws and statutes have requirements for what needs to be “conspicuous,” and certain provisions of contracts, like limitation of liability and disclaimers, are frequently capitalized to make them conspicuous.

The Uniform Commercial Code, the United States laws for commercial transactions, defines “conspicuous” like this:

So written, displayed, or presented that a reasonable person … ought to have noticed it. Whether a term is “conspicuous” or not is a decision for the court. Conspicuous terms include the following: (A) a heading in capitals equal to or greater in size than the surrounding text, or in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same or lesser size; and (B) language in the body of a record or display in larger type than the surrounding text, or in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same size, or set off from surrounding text of the same size by symbols or other marks that call attention to the language.

The crucial takeaway here is that the styling for conspicuous text doesn’t always have to be all caps. For a commercial contract, it could be something a lot more appealing that doesn’t make you feel like your new favorite social network is yelling at you. But some documents are reproduced for decades from boilerplate versions, so the caps get passed down through convention. There are also some laws and statutes (especially at the state level) that explicitly call for all caps in certain sections.

In a blog post from 2012, Luis Villa, the senior director of community engagement at the Wikimedia Foundation, suggested that the all-caps convention began with typewriters, which didn’t offer a lot of formatting options. “Unfortunately, at some point along the way, many lawyers confused the technology (typewriters) for what was actually legally required.”

One reason that user agreements in particular end up with a lot of all-caps sections is risk-aversion. If a contract makes its provisions “conspicuous,” it may be harder for someone to claim that he or she didn’t understand what they were agreeing to. A 2014 paper about conspicuous type by Mary Beth Beazley of Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law explains:

Sellers write disclaimers. Of course, they have no reason to write and present them in a way that is easy to understand, and every reason to write and present them in a way that discourages readers from looking closely at them. They are trying to increase profit and limit potential liability in every way they can. Sellers do not write disclaimers because they want buyers to know things. They write them so they can say to the buyer, “I told you so.”

Capitalism is always a good explanation for nonsensical intransigence, as is devotion to convention in law. But change is possible. In Typography for Lawyers, Matthew Butterick writes, “All-caps text —meaning text with all the letters capitalized—is best used sparingly. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use caps. Just use them judiciously.” Lawyers for tech companies, take note.