“Covenant”

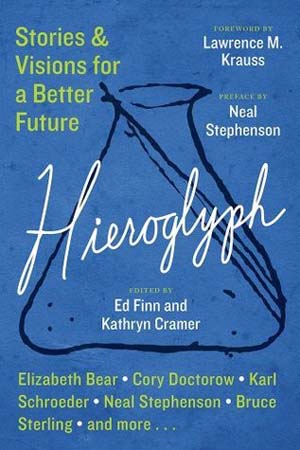

A short story from Hieroglyph, a new science fiction anthology.

Photo by pojoslaw/Thinkstock

This short story appears in the anthology Hieroglyph: Stories & Visions for a Better Future. On Thursday, Oct. 2, Future Tense—a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University—will present an event in Washington, D.C., on science fiction and public policy, inspired by Hieroglyph. For more information on the event and to RSVP, visit the New America website; for more on the Hieroglyph project, visit ASU’s Project Hieroglyph website.

This cold could kill me, but it’s no worse than the memories. Endurable as long as I keep moving.

My feet drum the snow-scraped roadbed as I swing past the police station at the top of the hill. Each exhale plumes through my mask, but insulating synthetics warm my inhalations enough so they do not sting and seize my lungs. I’m running too hard to breathe through my nose—running as hard and fast as I can, sprinting for the next hydrant-marking reflector protruding above a dirty bank of ice. The wind pushes into my back, cutting through the wet merino of my base layer and the wet MaxReg over it, but even with its icy assistance I can’t come close to running the way I used to run. Once I turn the corner into the graveyard, I’ll be taking that wind in the face.

I miss my old body’s speed. I ran faster before. My muscles were stronger then. Memories weigh something. They drag you down. Every step I take, I’m carrying 13 dead. My other self runs a step or two behind me. I feel the drag of his invisible, immaterial presence.

As long as you keep moving, it’s not so bad. But sometimes everything in the world conspires to keep you from moving fast enough.

I thump through the old stone arch into the graveyard, under the trees glittering with ice, past the iron gate pinned open by drifts. The wind’s as sharp as I expected—sharper— and I kick my jacket over to warming mode. That’ll run the battery down, but I’ve only got another 5 kilometers to go and I need heat. It’s getting colder as the sun rises, and clouds slide up the western horizon: cold front moving in. I flip the sleeve light off with my next gesture, though that won’t make much difference. The sky’s given light enough to run by for a good half-hour, and the sleeve light is on its own battery. A single LED doesn’t use much.

I imagine the flexible circuits embedded inside my brain falling into quiescence at the same time. Even smaller LEDs with even more advanced power cells go dark. The optogenetic adds shut themselves off when my brain is functioning healthily. Normally, microprocessors keep me sane and safe, monitor my brain activity, stimulate portions of the neocortex devoted to ethics, empathy, compassion. When I run, though, my brain—my dysfunctional, murderous, cured brain—does it for itself as neural pathways are stimulated by my own native neurochemicals.

Only my upper body gets cold: Though that wind chills the skin of my thighs and calves like an ice bath, the muscles beneath keep hot with exertion. And the jacket takes the edge off the wind that strikes my chest.

My shoes blur pink and yellow along the narrow path up the hill. Gravestones like smoker’s teeth protrude through swept drifts. They’re moldy black all over as if spray-painted, and glittering powdery whiteness heaps against their backs. Some of the stones date to the 18th century, but I run there only in the summertime or when it hasn’t snowed.

Maintenance doesn’t plow that part of the churchyard. Nobody comes to pay their respects to those dead anymore.

Sort of like the man I used to be.

The ones I killed, however—some of them still get their memorials every year. I know better than to attend, even though my old self would have loved to gloat, to relive the thrill of their deaths. The new me ... feels a sense of ... obligation. But their loved ones don’t know my new identity. And nobody owes me closure.

I’ll have to take what I can find for myself. I’ve sunk into that beautiful quiet place where there’s just the movement, the sky, that true, irreproducible blue, the brilliant flicker of a cardinal. Where I die as a noun and only the verb survives.

I run. I am running.

When he met her eyes, he imagined her throat against his hands. Skin like calves’ leather; the heat and the crack of her hyoid bone as he dug his thumbs deep into her pulse. The way she’d writhe, thrash, struggle.

His waist chain rattled as his hands twitched, jerking the cuffs taut on his wrists.

She glanced up from her notes. Her eyes were a changeable hazel: blue in this light, gray green in others. Reflections across her glasses concealed the corner where text scrolled. It would have been too small to read, anyway—backward, with the table he was chained to creating distance between them.

She waited politely, seeming unaware that he was imagining those hazel eyes dotted with petechiae, that fair skin slowly mottling purple. He let the silence sway between them until it developed gravity.

“Did you wish to say something?” she asked, with mild but clinical encouragement.

Point to me, he thought.

He shook his head. “I’m listening.”

She gazed upon him benevolently for a moment. His fingers itched. He scrubbed the tips against the rough orange jumpsuit but stopped. In her silence, the whisking sound was too audible.

She continued. “The court is aware that your crimes are the result of neural damage including an improperly functioning amygdala. Technology exists that can repair this damage. It is not experimental; it has been used successfully in tens of thousands of cases to treat neurological disorders as divergent as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, borderline personality, and the complex of disorders commonly referred to as schizophrenic syndrome.”

The delicate structure of her collarbones fascinated him. It took 14 pounds of pressure, properly applied, to snap a human clavicle—rendering the arm useless for a time. He thought about the proper application of that pressure. He said, “Tell me more.”

“They take your own neurons—grown from your own stem cells under sterile conditions in a lab, modified with microbial opsin genes. This opsin is a light-reactive pigment similar to that found in the human retina. The neurons are then reintroduced to key areas of your brain. This is a keyhole procedure. Once the neurons are established, and have been encouraged to develop the appropriate synaptic connections, there’s a second surgery, to implant a medical device: a series of miniaturized flexible microprocessors, sensors, and light-emitting diodes. This device monitors your neurochemistry and the electrical activity in your brain and adjusts it to mimic healthy activity.” She paused again and steepled her fingers on the table.

“ ‘Healthy,’ ” he mocked.

She did not move.

“That’s discrimination against the neuro-atypical.”

“Probably,” she said. Her fingernails were appliquéd with circuit diagrams. “But you did kill 13 people. And get caught. Your civil rights are bound to be forfeit after something like that.”

He stayed silent. Impulse control had never been his problem.

“It’s not psychopathy you’re remanded for,” she said. “It’s murder.”

“Mind control,” he said.

“Mind repair,” she said. “You can’t be sentenced to the medical procedure. But you can volunteer. It’s usually interpreted as evidence of remorse and desire to be rehabilitated. Your sentencing judge will probably take that into account.”

“God,” he said. “I’d rather have a bullet in the head than a fucking computer.”

“They haven’t used bullets in a long time,” she said. She shrugged, as if it were nothing to her either way. “It was lethal injection or the gas chamber. Now it’s rightminding. Or it’s the rest of your life in an 8-by-12 cell. You decide.”

“I can beat it.”

“Beat rightminding?”

Point to me.

“What if I can beat it?”

“The success rate is a hundred percent. Barring a few who never woke up from anesthesia.” She treated herself to a slow smile. “If there’s anybody whose illness is too intractable for this particular treatment, they must be smart enough to keep it to themselves. And smart enough not to get caught a second time.”

You’re being played, he told himself. You are smarter than her. Way too smart for this to work on you. She’s appealing to your vanity. Don’t let her yank your chain. She thinks she’s so fucking smart. She’s prey. You’re the hunter. More evolved. Don’t be manipulated—

His lips said, “Lady, sign me up.”

The snow creaks under my steps. Trees might crack tonight. I compose a poem in my head.

The fashion in poetry is confessional. It wasn’t always so—but now we judge value by our own voyeurism. By the perceived rawness of what we think we are being invited to spy upon. But it’s all art: veils and lies.

If I wrote a confessional poem, it would begin: Her dress was the color of mermaids, and I killed her anyway.

A confessional poem need not be true. Not true in the way the bite of the air in my lungs in spite of the mask is true. Not true in the way the graveyard and the cardinal and the ragged stones are true.

It wasn’t just her. It was her, and a dozen others like her. Exactly like her in that they were none of them the right one, and so another one always had to die.

That I can still see them as fungible is a victory for my old self—his only victory, maybe, though he was arrogant enough to expect many more. He thought he could beat the rightminding.

That’s the only reason he agreed to it.

If I wrote it, people would want to read that poem. It would sell a million—it would garner far more attention than what I do write.

I won’t write it. I don’t even want to remember it. Memory excision was declared by the Supreme Court to be a form of the death penalty, and therefore unconstitutional since 2043.

They couldn’t take my memories in retribution. Instead they took away my pleasure in them.

Not that they’d admit it was retribution. They call it repair. “Rightminding.” Fixing the problem. Psychopathy is a curable disease.

They gave me a new face, a new brain, a new name. The chromosome reassignment, I chose for myself, to put as much distance between my old self and my new as possible.

The old me also thought it might prove good will: reduced testosterone, reduced aggression, reduced physical strength. Few women become serial killers.

To my old self, it seemed a convincing lie.

He—no, I: alienating the uncomfortable actions of the self is something that psychopaths do—I thought I was stronger than biology and stronger than rightminding. I thought I could take anabolic steroids to get my muscle and anger back where they should be. I honestly thought I’d get away with it.

I honestly thought I would still want to.

I could write that poem. But that’s not the poem I’m writing. The poem I’m writing begins: Gravestones like smoker’s teeth ... except I don’t know what happens in the second clause, so I’m worrying at it as I run.

I do my lap and throw in a second lap because the wind’s died down and my heater is working and I feel light, sharp, full of energy and desire. When I come down the hill, I’m running on springs. I take the long arc, back over the bridge toward the edge of town, sparing a quick glance down at the frozen water. The air is warming up a little as the sun rises. My fingers aren’t numb in my gloves anymore.

When the unmarked white delivery van pulls past me and rolls to a stop, it takes me a moment to realize the driver wants my attention. He taps the horn, and I jog to a stop, hit pause on my run tracker, tug a headphone from my ear. I stand a few steps back from the window. He looks at me, then winces in embarrassment, and points at his navigation system. “Can you help me find Green Street? The autodrive is no use.”

“Sure,” I say. I point. “Third left, up that way. It’s an unimproved road; that might be why it’s not on your map.”

“Thanks,” he says. He opens his mouth as if to say something else, some form of apology, but I say, “Good luck, man!” and wave him cheerily on.

The vehicle isn’t the anomaly here in the country that it would be on a city street, even if half the cities have been retrofitted for urban farming to the point where they barely have streets anymore. But I’m flummoxed by the irony of the encounter, so it’s not until he pulls away that I realize I should have been more wary. And that his reaction was not the embarrassment of having to ask for directions, but the embarrassment of a decent, normal person who realizes he’s put another human being in a position where she may feel unsafe. He’s vanishing around the curve before I sort that out—something I suppose most people would understand instinctually.

I wish I could run after the van and tell him that I was never worried. That it never occurred to me to be worried. Demographically speaking, the driver is very unlikely to be hunting me. He was black. And I am white.

And my early fear socialization ran in different directions, anyway.

My attention is still fixed on the disappearing van when something dark and clinging and sweetly rank drops over my head.

I gasp in surprise and my filter mask briefly saves me. I get the sick chartreuse scent of ether and the world spins, but the mask buys me a moment to realize what’s happening—a blitz attack. Someone is kidnapping me. He’s grabbed my arms, pulling my elbows back to keep me from pushing the mask off.

I twist and kick, but he’s so strong.

Was I this strong? It seems like he’s not even working to hold on to me, and though my heel connects solidly with his shin as he picks me up, he doesn’t grunt. The mask won’t help forever—

—it doesn’t even help for long enough.

Ether dreams are just as vivid as they say.

His first was the girl in the mermaid-colored dress. I think her name was Amelie. Or Jessica. Or something. She picked him up in a bar. Private cars were rare enough to have become a novelty, even then, but he had my father’s Mission for the evening. She came for a ride, even though—or perhaps because—it was a little naughty, as if they had been smoking cigarettes a generation before. They watched the sun rise from a curve over a cornfield. He strangled her in the backseat a few minutes later.

She heaved and struggled and vomited. He realized only later how stupid he’d been. He had to hide the body, because too many people had seen us leave the bar together.

He never did get the smell out of the car. My father beat the shit out of him and never let him use it again. We all make mistakes when we’re young.

I awaken in the dying warmth of my sweat-soaked jacket, to the smell of my vomit drying between my cheek and the cement floor. At least it’s only oatmeal. You don’t eat a lot before a long run. I ache in every particular, but especially where my shoulder and hip rest on concrete. I should be grateful; he left me in the recovery position so I didn’t choke.

It’s so dark I can’t tell if my eyelids are open or closed, but the hood is gone and only traces of the stink of the ether remain. I lie still, listening and hoping my brain will stop trying to split my skull.

I’m still dressed as I was, including the shoes. He’s tied my hands behind my back, but he didn’t tape my thumbs together. He’s an amateur. I conclude that he’s not in the room with me. And probably not anywhere nearby. I think I’m in a cellar. I can’t hear anybody walking around on the floor overhead.

I’m not gagged, which tells me he’s confident that I can’t be heard even if I scream. So maybe I wouldn’t hear him up there, either?

My aloneness suggests that I was probably a target of opportunity. That he has somewhere else he absolutely has to be. Parole review? Dinner with the mother who supports him financially? Stockbroker meeting? He seems organized; it could be anything. But whatever it is, it’s incredibly important that he show up for it, or he wouldn’t have left.

When you have a new toy, can you resist playing with it? I start working my hands around. It’s not hard if you’re fit and flexible, which I am, though I haven’t kept in practice. I’m not scared, though I should be. I know better than most what happens next. But I’m calmer than I have been since I was somebody else. The adrenaline still settles me, just like it used to. Only this time—well, I already mentioned the irony.

It’s probably not even the lights in my brain taking the edge off my arousal.

The history of technology is all about unexpected consequences. Who would have guessed that peak oil would be linked so clearly to peak psychopathy? Most folks don’t think about it much, but people just aren’t as mobile as they—as we—used to be. We live in populations of greater density, too, and travel less. And all of that leads to knowing each other more.

People like the nameless him who drugged me—people like me—require a certain anonymity, either in ourselves or in our victims.

The floor is cold against my rear end. My gloves are gone. My wrists scrape against the soles of my shoes as I work the rope past them. They’re only a little damp, and the water isn’t frozen or any colder than the floor. I’ve been down here awhile, then—still assuming I am down. Cellars usually have windows, but guys like me—guys like I used to be—spend a lot of time planning in advance. Rehearsing. Spinning their webs and digging their holes like trapdoor spiders.

I’m shivering, and my body wants to cramp around the chill. I keep pulling. One more wiggle and tug, and I have my arms in front of me. I sit up and stretch, hoping my kidnapper has made just one more mistake. It’s so dark I can’t see my fluorescent yellow-and-green running jacket, but proprioception lets me find my wrist with my nose. And there, clipped into its little pocket, is the microflash sleeve light that comes with the jacket.

He got the mask—or maybe the mask just came off with the bag. And he got my phone, which has my tracker in it, and a GPS. He didn’t make the mistake I would have chosen for him to make.

I push the button on the sleeve light with my nose. It comes on shockingly bright, and I stretch my fingers around to shield it as best I can. Flesh glows red between the bones.

Yep. It’s a basement.

Eight years after my first time, the new, improved me showed the IBI the site of the grave he’d dug for the girl in the mermaid-colored dress. I’d never forgotten it—not the gracious tree that bent over the little boulder he’d skidded on top of her to keep the animals out, not the tangle of vines he’d dragged over that, giving himself a hell of a case of poison ivy in the process.

This time, I was the one who vomited.

How does one even begin to own having done something like that? How do I?

Ah, there’s the fear. Or not fear, exactly, because the optogenetic and chemical controls on my endocrine system keep my arousal pretty low. It’s anxiety. But anxiety’s an old friend.

It’s something to think about while I work on the ropes and tape with my teeth. The sleeve light shines up my nose while I gnaw, revealing veins through the cartilage and flesh. I’m cautious, nipping and tearing rather than pulling. I can’t afford to break my teeth: they’re the best weapon and the best tool I have. So I’m meticulous and careful, despite the nauseous thumping of my heart and the voice in my head that says, Hurry, hurry, he’s coming.

He’s not coming—at least, I haven’t heard him coming. Ripping the bonds apart seems to take forever. I wish I had wolf teeth, teeth for slicing and cutting. Teeth that could scissor through this stuff as if it were a cheese sandwich. I imagine my other self’s delight in my discomfort, my worry. I wonder if he’ll enjoy it when my captor returns, even though he’s trapped in this body with me.

Does he really exist, my other self? Neurologically speaking, we all have a lot of people in our heads all the time, and we can’t hear most of them. Maybe they really did change him, unmake him. Transform him into me. Or maybe he’s back there somewhere, gagged and chained up, but watching.

Whichever it is, I know what he would think of this. He killed 13 people. He’d like to kill me, too.

I’m shivering.

The jacket’s gone cold, and it—and I—am soaked. The wool still insulates while wet, but not enough. The jacket and my compression tights don’t do a damned thing.

I wonder if my captor realized this. Maybe this is his game.

Considering all the possibilities, freezing to death is actually not so bad.

Maybe he just doesn’t realize the danger? Not everybody knows about cold.

The last wrap of tape parts, sticking to my chapped lower lip and pulling a few scraps of skin loose when I tug it free. I’m leaving my DNA all over this basement. I spit in a corner, too, just for good measure. Leave traces: even when you’re sure you’re going to die. Especially then. Do anything you can to leave clues.

It was my skin under a fingernail that finally got me.

The period when he was undergoing the physical and mental adaptations that turned him into me gave me a certain ... not sympathy, because they did the body before they did the rightminding, and sympathy’s an emotion he never felt before I was 33 years old ... but it gave him and therefore me a certain perspective he hadn’t had before.

It itched like hell. Like puberty.

There’s an old movie, one he caught in the guu this one time. Some people from the future go back in time and visit a hospital. One of them is a doctor. He saves a woman who’s waiting for dialysis or a transplant by giving her a pill that makes her grow a kidney.

That’s pretty much how I got my ovaries, though it involved stem cells and needles in addition to pills.

I was still him, because they hadn’t repaired the damage to my brain yet. They had to keep him under control while the physical adaptations were happening. He was on chemical house arrest. Induced anxiety disorder. Induced agoraphobia.

It doesn’t sound so bad until you realize that the neurological shackles are strong enough that even stepping outside your front door can put you on the ground. There are supposed to be safeguards in place. But everybody’s heard the stories of criminals on chemarrest who burned to death because they couldn’t make themselves walk out of a burning building.

He thought he could beat the rightminding, beat the chemarrest. Beat everything.

Damn, I was arrogant.

My former self had more grounds for his arrogance than this guy. This is pathetic, I think. And then I have to snort laughter, because it’s not my former self who’s got me tied up in this basement.

I could just let this happen. It’d be fair. Ironic. Justice.

And my dying here would mean more women follow me into this basement. One by one by one.

I unbind my ankles more quickly than I did the wrists. Then I stand and start pacing, do jumping jacks, jog in place while I shine my light around. The activity eases the shivering. Now it’s just a tremble, not a teeth-rattling shudder. My muscles are stiff; my bones ache. There’s a cramp in my left calf.

There’s a door locked with a deadbolt. The windows have been bricked over with new bricks that don’t match the foundation. They’re my best option—if I could find something to strike with, something to pry with, I might break the mortar and pull them free.

I’ve got my hands. My teeth. My tiny light, which I turn off now so as not to warn my captor.

And a core temperature that I’m barely managing to keep out of the danger zone.

When I walked into my court-mandated therapist’s office for the last time—before my relocation—I looked at her creamy complexion, the way the light caught on her eyes behind the glasses. I remembered what he’d thought.

If a swell of revulsion could split your own skin off and leave it curled on the ground like something spoiled and disgusting, that would have happened to me then. But of course it wasn’t my shell that was ruined and rotten; it was something in the depths of my brain.

“How does it feel to have a functional amygdala?” she asked.

“Lousy,” I said.

She smiled absently and stood up to shake my hand—for the first time. To offer me closure. It’s something they’re supposed to do.

“Thank you for all the lives you’ve saved,” I told her.

“But not for yours?” she said.

I gave her fingers a gentle squeeze and shook my head.

My other self waits in the dark with me. I wish I had his physical strength, his invulnerability. His conviction that everybody else in the world is slower, stupider, weaker.

In the courtroom, while I was still my other self, he looked out from the stand into the faces of the living mothers and fathers of the girls he killed. I remember the 11 women and seven men, how they focused on him. How they sat, their stillness, their attention.

He thought about the girls while he gave his testimony. The only individuality they had for him was what was necessary to sort out which parents went with which corpse; important, because it told him whom to watch for the best response.

I wish I didn’t know what it feels like to be prey. I tell myself it’s just the cold that makes my teeth chatter. Just the cold that’s killing me.

Prey can fight back, though. People have gotten killed by something as timid and inoffensive as a white-tailed deer.

I wish I had a weapon. Even a cracked piece of brick. But the cellar is clean.

I do jumping jacks, landing on my toes for silence. I swing my arms. I think about doing burpees, but I’m worried that I might scrape my hands on the floor. I think about taking my shoes off. Running shoes are soft for kicking with, but if I get outside, my feet will freeze without them.

When. When I get outside.

My hands and teeth are the only weapons I have.

An interminable time later, I hear a creak through the ceiling. A footstep, muffled, and then the thud of something dropped. More footsteps, louder, approaching the top of a stair beyond the door.

I crouch beside the door, on the hinge side, far enough away that it won’t quite strike me if he swings it violently. I wish for a weapon—I am a weapon—and I wait.

A metallic tang in my mouth now. Now I am really, truly scared.

His feet thump on the stairs. He’s not little. There’s no light beneath the door—it must be weather-stripped for soundproofing. The lock thuds. A bar scrapes. The knob rattles, and then there’s a bar of light as it swings open. He turns the flashlight to the right, where he left me lying. It picks out the puddle of vomit. I hear his intake of breath.

I think about the mothers of the girls I killed. I think, Would they want me to die like this?

My old self would relish it. It’d be his revenge for what I did to him.

My goal is just to get past him—my captor, my old self; they blur together—to get away, run. Get outside. Hope for a road, neighbors, bright daylight.

My captor’s silhouette is dim, scatter-lit. He doesn’t look armed, except for the flashlight, one of those archaic long heavy metal ones that doubles as a club. I can’t be sure that’s all he has. He wavers. He might slam the door and leave me down here to starve—

I lunge.

I grab for the wrist holding the light, and I half catch it, but he’s stronger. I knew he would be. He rips the wrist out of my grip, swings the flashlight. Shouts. I lurch back, and it catches me on the shoulder instead of across the throat. My arm sparks pain and numbs. I don’t hear my collarbone snap. Would I, if it has?

I try to knee him in the crotch and hit his thigh instead. I mostly elude his grip. He grabs my jacket; cloth stretches and rips. He swings the light once more. It thuds into the stair wall and punches through drywall. I’m half past him and I use his own grip as an anchor as I lean back and kick him right in the center of the nose. Soft shoes or no soft shoes.

He lets go, then. Falls back. I go up the stairs on all fours, scrambling, sure he’s right behind me. Waiting for the grab at my ankle. Halfway up I realize I should have locked him in. Hit the door at the top of the stairs and find myself in a perfectly ordinary hallway, in need of a good sweep. The door ahead is closed. I fumble the lock, yank it open, tumble down steps into the snow as something fouls my ankles.

It’s twilight. I get my feet under me and stagger back to the path. The shovel I fell over is tangled with my feet. I grab it, use it as a crutch, lever myself up and stagger-run-limp down the walk to a long driveway.

I glance over my shoulder, sure I hear breathing.

Nobody. The door swings open in the wind.

Oh. The road. No traffic. I know where I am. Out past the graveyard and the bridge. I run through here every couple of days, but the house is set far enough back that it was never more than a dim white outline behind trees. It’s a Craftsman bungalow, surrounded by winter-sere oaks.

Maybe it wasn’t an attack of opportunity, then. Maybe he saw me and decided to lie in wait.

I pelt toward town—pelt, limping, the air so cold in my lungs that they cramp and wheeze. I’m cold, so cold. The wind is a knife. I yank my sleeves down over my hands. My body tries to draw itself into a huddled comma even as I run. The sun’s at the horizon.

I think, I should just let the winter have me.

Justice for those 11 mothers and seven fathers. Justice for those 13 women who still seem too alike. It’s only that their interchangeability bothers me now.

At the bridge I stumble to a dragging walk, then turn into the wind off the river, clutch the rail, and stop. I turn right and don’t see him coming. My wet fingers freeze to the railing.

The state police are half a mile on, right around the curve at the top of the hill. If I run, I won’t freeze before I get there. If I run.

My fingers stung when I touched the rail. Now they’re numb, my ears past hurting. If I stand here, I’ll lose the feeling in my feet.

The sunset glazes the ice below with crimson. I turn and glance the other way; in a pewter sky, the rising moon bleaches the clouds to moth-wing iridescence.

I’m wet to the skin. Even if I start running now, I might not make it to the station house. Even if I started running now, the man in the bungalow might be right behind me. I don’t think I hit him hard enough to knock him out. Just knock him down.

If I stay, it won’t take long at all until the cold stops hurting.

If I stay here, I wouldn’t have to remember being my other self again. I could put him down. At last, at last, I could put those women down. Amelie, unless her name was Jessica. The others.

It seems easy. Sweet.

But if I stay here, I won’t be the last person to wake up in the bricked-up basement of that little white bungalow.

The wind is rising. Every breath I take is a wheeze. A crow blows across the road like a tattered shirt, vanishing into the twilight cemetery.

I can carry this a little farther. It’s not so heavy. Thirteen corpses, plus one. After all, I carried every one of them before.

I leave skin behind on the railing when I peel my fingers free. Staggering at first, then stronger, I sprint back into town.

At hieroglyph.asu.edu/covenant, Elizabeth Bear discusses the ethical and practical aspects of hacking the human mind and discusses neuroplasticity with and other Hieroglyph community members.

Copyright © 2014 Sarah Wishnevsky. Reprint permission from William Morrow/HarperCollins.