Tennis: An Aural History

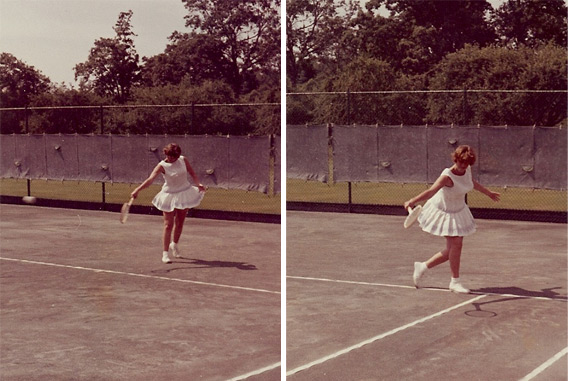

Victoria Heinicke, the sport's first grunter. Plus: Notes on the evolution of grunting.

Novak Djokovic's four-set win over Rafael Nadal in Monday's U.S. Open final was brutal, lengthy, and loud. As Nadal strained to match Djokovic's power and precision, the long rallies became metronomic: forehand, groan, backhand, groan, forehand, groan. Sometimes Djokovic would join in, too, creating a grunt-to-grunt rally to parallel the one with the ball and rackets.

Nadal, Djokovic, Andy Murray, Serena Williams, Victoria Azarenka, Maria Sharapova—nearly every top player grunts or groans or shrieks. It wasn't always that way. In the middle of the 20th century, tennis was a pretty quiet game. Then a teenage girl—a player at the sport's highest level for just a few years—came along and ended tennis' silent era.

Though the history of grunting in tennis is sketchy, there's rough agreement on when the phenomenon began. Bud Collins, the 82-year-old dean of tennis journalism, says he first heard an on-court grunt in the 1960s. In a 1984 Sports Illustrated story, now-deceased tennis player, spy, and fashion designer Ted Tinling told Frank Deford that grunting hit the sport in 1959.

Though Tinling didn't name names, Collins has said multiple times that the first grunter he can remember was a junior player from Arizona named Vicki Palmer. Contemporaneous accounts support this claim. A 1962 SI piece on the National Singles Championships at Forest Hills, N.Y., which later became the U.S. Open, mentions "a number of dramatic upsets, including … Wimbledon champion Karen Hantze Susman by 17-year-old Vicki Palmer—indelicately nicknamed The Grunter." (That 1962 tournament also featured "one Hugh Sweeney, who may quite possibly be the last man ever to play tournament tennis in long white flannel pants.")

Sports Illustrated chronicled Palmer's many triumphs in those years. She first appeared in the magazine in 1957, when "the 12-year-old mite who stands not quite 5 feet tall scampered off with three trophies in [the] Arizona Tennis Open." A year later, the "13-year-old tennis power" won the national under-15 tournament. In 1959, the magazine reported that she "is strong, plays an excellent backcourt game and has apparently overcome an indifference toward victory." Four years hence, SI documented her upset of Billie Jean Moffitt (the soon-to-be Billie Jean King) in the quarterfinals of the national clay court championships. That was the last time Palmer's name appeared in SI. What happened to The Grunter, and why did she start grunting in the first place?

I tracked down the 66-year-old Victoria Palmer Heinicke in Colorado Springs, Col., where she's a retired tech support consultant. (Though the papers referred to her as Vicki, Heinicke says she's always preferred Victoria.) Heinicke says she can't recall anybody ever interviewing her about how she changed the sound of tennis. "The top players grunted occasionally, but I was the only one who did it consistently," she says.

Heinicke learned tennis from her father in Arizona, starting at four-and-a-half. For as long as she can remember, she grunted when she hit the ball. It's not a genetic thing—none of her five brothers and sisters grunted when they played tennis. And she didn't grunt—as Heinicke remembers tennis legend Maureen "Little Mo" Connolly theorizing as a television commentator—because her father had coached her on how to expel air more efficiently. "The reason I grunted was that it was the way I breathe[d] when I hit the ball," she says.

What did the legendary grunt sound like? Collins tells me that "it was loud, and it was kind of startling." According to Heinicke, it wasn't high-pitched like Michelle Larcher de Brito's screech, and it wasn't as extended as Victoria Azarenka's tea-kettle whistle. Heinicke says her grunt was compact, a low-register thud as she hit the ball and followed through. In search of a modern analogue, she compares her grunting style to that of hard-hitting Spanish baseliner David Ferrer.

Some tennis players claim that grunting helps them hit harder, although it could be the reverse: The more effort you put into your swing, the deeper (and louder) your exhalation. Either way, Heinicke was known as a hard-hitter. The former junior star says she hit quite forcefully for the wooden-racket era—former world No. 5 Julie Heldman, who played against Heinicke, confirms that "she could slug the ball"—and believes the effort she expended on each stroke accounted for her noisemaking.

While Heinicke's proto-grunting was a topic of conversation among her fellow players, it was never all that controversial. Tennis Hall of Famer Nancy Richey, who beat Heinicke to win 1963's national clay court championships, says that though most of her contemporaries made a bit of noise, Heinicke "was probably the loudest." Still, Richey says "it wasn't anything you would complain about," explaining that her contemporary's decibel level doesn't compare to today's piercing shrieks. In fact, she found her opponent's grunting beneficial. "You know she's doing it at the moment of contact with the ball," Richey says. "In a sense, it helps your timing."

Only one time, Heinicke says, did her grunting almost get her into trouble. One year, in advance of Wimbledon, a player who she had faced many times (and who she declines to name) asked the tournament referee to stop her from grunting. Heinicke thinks it was probably gamesmanship—a ploy to mess with her head. The referee denied the request, the grunter and the complainer didn't end up facing each other, and Heinicke never changed her sound.

Heinicke's career came to an early end, though her retirement had nothing to do with noise. At the age of 18, she skipped Forest Hills and Wimbledon and enrolled at the University of Arizona, which didn't have a women's tennis team. (She practiced with the men.) Soon after, she got married, and had her first child when she was 19. At that point, she stopped playing competitive tennis.

In the early 1960s, top women's players got their rackets for free, but there was no prize money at the national singles championships or the junior nationals. Traveling across the country for tournaments was an expensive, unappealing proposition for Heinicke and her young family. "Gladys Heldman and Billie Jean King started women's pro tennis, and that was a very difficult life," she says. "They were on the road and traveling across the country on buses. That was not something that I wanted to do."

After Heinicke left the sport, the best players of the 1970s—Chris Evert, Tracy Austin, Andrea Jaeger, and Jimmy Connors—nurtured grunts of their own. As the grunts grew more forceful, so did the calls to press the mute button. In 1981, an umpire at Wimbledon asked Connors—whose on-court growl fit in with his blue-collar image—to tone it down. "I told him there was nothing I could do and he could only default me," Connors told reporters after the match, adding derisively that "I am grunting well this year." Connors was not defaulted, making this the first in a long series of ineffectual pleas for comprehensive grunting reform.

The terrain shifted in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as the Nick Bollettieri-schooled Monica Seles and Andre Agassi pumped up the volume. Ted Tinling once referred to Seles' grunt as sounding "like a Christmas goose being strangled to death." Others compared it to a "grunt right out of a pig sty" or "the wail of strangled bagpipes." It wasn't just the press and Wimbledon officials who complained—Seles and Agassi drew increasing ire from their sonically terrorized opponents.

At Wimbledon in 1992—the genteel All England Club has often served as the sport's noise battleground —Martina Navratilova twice groused to the chair umpire about Seles' grunting during their semifinal match. While Nancy Richey says that Heinicke's grunts helped with her timing, Navratilova argued that Seles' louder wails prevented her from hearing ball hit racket. (A recent study, which found that grunts slowed down opponents' reaction time, backs Navratilova's point.) Navratilova also complained that Seles' intonation changed throughout the match. In that sense, the Seles sound was arguably a hindrance—something akin to the distracting "Come on!" of Serena Williams.

"There were two or three points when I said, Monica, don't grunt, don't grunt," Seles said after her match against Navratilova, explaining why she couldn't quiet down. "But you know, it's such a tense match." Stung by Navratilova's criticism and the mockery of the London tabloids' "Grunt-o-Meters," Seles forced herself to play the Wimbledon final against Steffi Graf in eerie silence. In her autobiography, Seles says this decision is "one of the only things I've regretted in my life." Though she'd just beaten her German rival to win the French Open, this time Seles was routed 6-2, 6-1. A short time later, Seles ended her brief grunt interregnum, and she trounced Arantxa Sanchez-Vicario to win the U.S. Open. (A few months after that, Seles was stabbed on the court by a madman. She won just one more grand slam title.)

Heinicke says Seles' struggles during her quiet period are easy to understand. "I wouldn't have been able to play, bottom line, if they had banned grunting," she says. "That's how I hit the ball. And I'd say that a lot of the tennis players [now] wouldn't be able to stop [either]."

Though she says today's louder, shriller players don't bother her, it's telling that Heinicke compared her grunt to that of David Ferrer. The game's earliest grunters, both men and women, sounded like today's male players, emitting a guttural unnngh upon making contact with the ball. The Sharapova and Azarenka screams sound less natural and less necessary. Bud Collins believes referees should use the hindrance rule—the regulation that cost Williams a point when she screamed against Samantha Stosur—to penalize the loudest grunters. Nancy Richey suggests that tennis implement an official, London-tabloid-esque Grunt-o-Meter and punish players who cross a noise threshold. Her suggested outer limit: "as loud as a lawnmower."

Along with Richey, retired greats Evert and Navratilova have both spoken out about the game's rising noise level, with the latter saying that grunting "is cheating, pure and simple." It's no coincidence that Navratilova was the one to call out Seles: By 1992, she was 35 years old, a relic from a more peaceful age. Serena Williams, by contrast, grew up idolizing Seles. "I loved her game. I loved her grunt," Williams told ESPN.com's Darren Rovell in 2005. "So my grunt is kind of like hers a little bit, where it's like a double-grunt." Since most of this generation's top pros grew up grunting, they have no incentive to end the shrieking era. From their perspective, a noise ban would be mutually assured destruction.

For her part, Heinicke doesn't believe today's lawnmower sounds are her legacy. "When I was young I did well," she says, "and it had nothing to do with my grunting." Besides, even the loudest grunters bug her less than players who stall between points—back when she played, nobody even sat down during changeovers. The other major difference between tennis then and now: television. The same equipment that allows viewers to hear racket hit ball also amplifies whatever sounds come out of the players' mouths. "When I played the microphones never picked up my grunting," she told me via email. "We have come a long way electronically!!!"