The Captain of Crunch

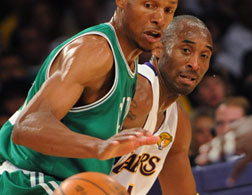

Is Kobe Bryant really the best clutch player in the NBA?

To hear Stefan Fatsis, Josh Levin, and Mike Pesca discuss the NBA Finals, click the arrow on the audio player below and fast-forward to the 1:50 mark:

You can also download the podcast, or you can subscribe to the weekly Hang Up and Listen podcast feed in iTunes.

Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant isn't just looking for his fifth ring in the 2010 NBA Finals. The Black Mamba is also hoping to cement his second nickname. ABC's Mark Jackson, a devoted Kobephile, often refers to Bryant as "the best closer in basketball."Sports Illustrated's Chris Mannix recently called Bryant "the game's most cold-blooded closer." The New York Times' Howard Beck, too, deemed Bryant "the NBA's ultimate closer."Oakland Tribune columnist Monte Poole wrote that Bryant isn't just the best closer in basketball, "he's the best closer in sports."

Bryant did not succeed in closing out Sunday night's Game 2, a nine-point victory by the Boston Celtics. Still, if Game 3 is on the line, the Lakers will give the ball to Kobe. Not that it should surprise Boston: In a 2009 Sports Illustrated poll, 76 percent of NBA players chose him as the player they'd want to take the last shot with the game on the line. (The next closest, Chauncey Billups, received 3 percent of the votes.) Chances are the players didn't pore over the encyclopedic basketball stats Web site 82 Games before weighing in. If they had, his colleagues would have found that while Bryant does excel late in games, his clutchness is definitely overrated.

The topic of "clutch" is a contentious one in sports. In baseball, the debate over clutch hitting has raged for decades, with sabermetricians arguing there's no evidence it's an actual skill and wizened baseball men claiming they've seen it with their own two eyes. In basketball, a sport that's been slower to embrace modern statistics, the fight over clutchness is in its relative infancy. Perhaps Kobe Bryant, then, will become the NBA's Derek Jeter: a player whom the media and the fans perceive as clutch despite a lack of statistical evidence to prove the case.

The Kobe-as-closer idea kicked into gear this season as Bryant sank six game-winning shots, each more spectacular than the last. On Dec. 4 against the Miami Heat, for example, he banked in a 3-pointer at the buzzer off one foot with Dwyane Wade in his face. As fans, though, we tend to remember the makes and forget the misses. According to 82 Games, Bryant missed the most potentially game-winning shots (42) of anyone in the NBA from 2003-04 through the middle of the 2008-09 season. (In this study, a game-winning shot was defined as one taken with 24 seconds or less remaining and the score tied or the team with the ball down by 1 or 2 points.) While Bryant was fourth in the NBA in game-winners (14) over that period—behind LeBron James, Vince Carter, and Ray Allen—his .250 game-winning shooting percentage was below the league average of .298. That .250 mark was also the second-worst of anyone with at least six game-winning baskets, behind only the SI poll's second-favorite clutch performer, Chauncey Billups. (Some of the league's best late-game shooters by percentage: Carmelo Anthony, Antawn Jamison, and Pau Gasol.)

Clutchness doesn't always come down to whether you make a shot at the buzzer. If we go with the definition proffered by 82 Games, "clutch" situations are those with less than five minutes left in the fourth quarter or in overtime and neither team ahead by more than five points. At first glance, Bryant seems to pulverize opponents in these close-and-late scenarios: He was second in the league this season in points scored per 48 minutes in the clutch (51.2), first in 2008-09 (56.7), and second in 2007-08 (51.8).

But again, point totals don't tell the whole story—it also matters how often you make the clutch shots you take. I called upon David J. Berri, an economics professor at Southern Utah University and the co-author of Stumbling on Wins, to help me determine how Bryant's clutch shooting percentage compared to his peers. First, Berri determined which players took the most shots in the clutch over the past few regular seasons. According to his data, 49 players compiled at least 100 clutch minutes and averaged at least 16 field goal attempts per 48 clutch minutes in 2009-2010. While Bryant had the second-highest scoring average in this group of 49, he did it while averaging the second most field goal attempts. That left the Lakers star 17th in clutch field goal percentage (.444) in 2009-10, behind players like Andrea Bargnani and Zach Randolph. Bryant didn't do any better the previous two seasons, finishing 21st out of 59 qualifying players in clutch shooting percentage in 2008-09 and 24th out of 59 in 2007-08. (In all three years, his standard field goal percentage was slightly better than his clutch shooting percentage.)

Bryant also doesn't look particularly clutch if you judge him by Berri's advanced stats. In the service of our clutchness study, the economist narrowed the scope of his Wins Produced per 48 minutes metric to players who have logged at least 100 minutes of clutch time. After breaking down the past three regular seasons, Berri discovered that Bryant was 17th among qualifiers in WP48 Clutch in 2009-10, fourth in 2008-09, and 21st in 2007-08. (In all three seasons, Bryant's WP48 Clutch number was an improvement over his standard WP48, meaning that by this measure, he performed better in the clutch than in regular game situations.)

Berri's numbers, however, don't include the part of the season where legends are made: the playoffs. According to that 82 Games study of game-winning shots, Bryant and LeBron James are tied with the most playoff game-winners (four) from 2003 to 2008. Considering that small sample size, we need more data to figure out if The Closer closes out NBA playoff games. To that end, I contacted Wayne Winston, a professor at Indiana University and a former consultant for the Dallas Mavericks. To evaluate a player's performance late in games, Winston used an adjusted fourth quarter plus-minus rating, which (as defined by 82 Games) "indicate[s] how many additional points are contributed to a team's scoring margin by a given player in comparison to the league-average player over the span of a typical game." In this case, Winston shortened the span from a typical game to just the fourth quarter. Over the past four seasons—including the 2009-10 playoffs and Game 1 of this year's NBA Finals—Bryant has excelled late in games, but he isn't the best closer in basketball. According to Winston's calculations, that title belongs to LeBron James, who has a fourth quarter plus-minus rating of +21. Dwyane Wade is second in the league at +12 and Bryant is tied for third with Tim Duncan at +11.

Berri's numbers agree with Winston's: The King is a better closer than Black Mamba. James' Wins Produced per 48 minutes number skyrocketed from .441 to .893 in the clutch (first in the NBA) during the 2009-10 regular season, from .426 to .944 in the clutch (first in the NBA) during the 2008-09 regular season, and from .327 to .550 in the clutch (second in the NBA) during the 2007-08 regular season. (Bryant's WP48 Clutch numbers in those years are anemic by comparison: .282, .429, and .300.)

What accounts for James' greatness in the clutch? Essentially, almost every facet of his game improves when the game is on the line. "Most importantly, [James] improved with respect to shooting efficiency and rebounds," Berri explained via e-mail. "Kobe also improved by lesser amounts with respect to rebounds and free throws. But he also got worse with respect to shooting efficiency from the field, assists, blocked shots, and steals. Basically each player tries to do more in the clutch. But LeBron is better at turning this effort into results."

LeBron's ability in the clutch can be quantified in other ways. He led the league in points per 48 minutes of clutch time in 2009-10 (66.1) and 2007-08 (56.0), and finished second (55.9) to Bryant in 2008-09. He also had a better clutch field goal percentage per 48 minutes than Bryant in 2009-10 (.488, ninth), 2008-09 (.556, second), and 2007-08 (.475, 16th). And according to 82 Games, James also had six game-winning assists from 2003 to 2009, while Bryant had just one assist to go along with his 56 shot attempts.

So, does LeBron James' run of clutchness mean that there is such a thing as clutch ability in basketball? Berri says that a couple of years of LeBron and Kobe stats aren't enough to help us reach a general conclusion. All we can say at this point, the economist believes, "is that Kobe is not the most clutch player in the history of the universe (or whatever Kobe fans assert)."

Behavorial economist Daniel Ariely argues that a player's clutchness is a fiction based more on social agreement than on performance. In a study, Ariely asked a group of professional coaches who they thought were the NBA's best clutch players. Not surprisingly, the same set of stars kept coming up, including Bryant, James, Wade, and Duncan. Ariely then compared the performances of alleged clutch players with those were not explicitly identified as clutch. "As it turned out, the clutch players did not improve their skill; they just [shot the ball] many more times," Ariely wrote in a recent piece for the Huffington Post. "Their field goal percentage did not increase in the last five minutes. … [N]either was it the case that non-clutch players got worse."

Before latching on to pro basketball players, Ariely initially set out to study Wall Street bankers—another group that fights for supremacy as a part of highly selective teams. Ariely says he heard the same things about the bankers and the athletes: They're not regular people. They thrive on stress. Indeed, that SI poll about late-game heroes shows that Bryant's colleagues don't see him as a regular person, that they believe he thrives on stress. Kobe might be the best basketball player alive, and he very well could hit a game-winning shot in the NBA Finals. He's doesn't, however, have a unique ability to score in the clutch. The only reason he's The Closer is that his teammates, his coach, and the sports media have chosen him to assume the role.

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.